Special Report: Should Coal Country Roll Back State Laws and Rely on Feds?

By Marissa Horn, Stephen Joyce, Paul Connolly, and Dean Scott

May 4, 2017 - Changes to coal mine inspection regulations in mining mainstays such as Kentucky and West Virginia are the latest in legislative pushes to roll back state mine inspections and yield to federal oversight. But, some regulatory specialists say states should not rely too much on federal inspectors to ensure safety for some of President Donald Trump’s most ardent supporters: coal miners.

State legislators, lawyers and academics disagree about just how much states should rely on the federal government to safeguard their coal miners. While some West Virginia lawmakers claimed their state could curtail inspections to save money because of a federal coal-mine backstop, others said the perilous nature of miners’ work demands inspection vigilance. West Virginia is the latest, but not the first, to restructure the state’s responsibilities for mine safety obligations.

Gov. Jim Justice (D) April 27 signed a bill that will make the oversight of the inspections more efficient. It replaced a bill introduced earlier in the state’s legislative session that would have stripped safety investigators of their ability to conduct inspections and instead charged them with “compliance visits and education.”

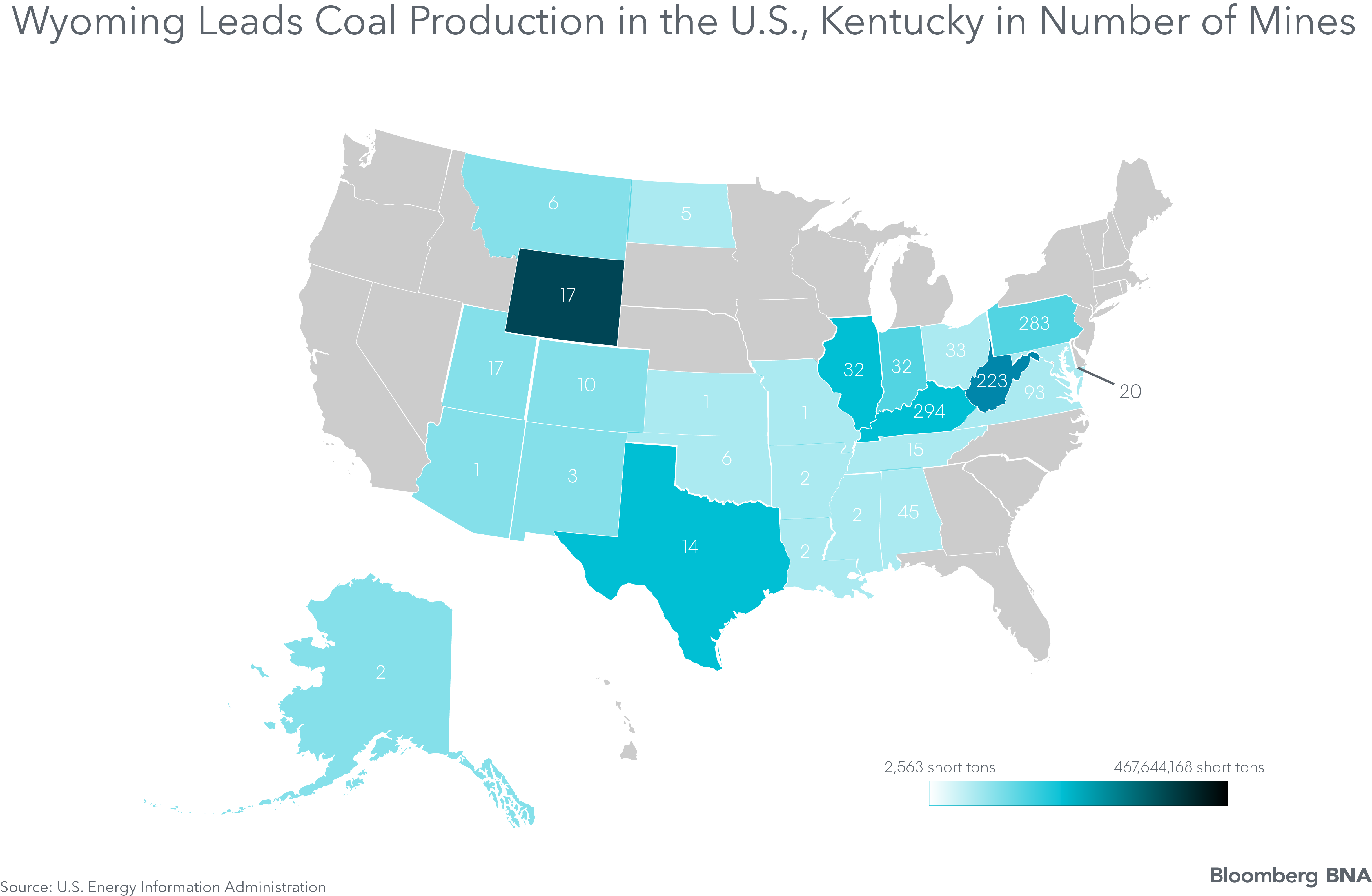

“West Virginia, Kentucky and Pennsylvania are frankly the last states with any inspections laws with any teeth to them,” Phil Smith, United Mine Workers of America spokesman, told Bloomberg BNA. “Alabama has completely eliminated its inspectors, Illinois and Indiana have done the same and those are the only states that ever had any of those sorts of laws with any teeth to them. There really isn’t a whole lot left.”

“The state is essentially getting out of the business of protecting its own coal miners there and leaving that to the federal government,” Smith said. “At the same time the federal government is cutting back on the number of inspectors that will be in the state.”

That backstop may be narrowed with the Trump administration’s push to slash agency budgets, including the Labor Department. The deep cuts could negatively affect the Mine Safety and Health Administration, a Labor Department unit that inspects all U.S. coal mines to enforce federal safety and health rules. The president has also yet to name a head for the agency, adding uncertainty to the federal government’s future role in mine safety.

“If he’s really for the miners, which seem to be in his constituency, then he would be for active regulation,” Sidney Shapiro, a Wake Forest School of Law professor, said.

‘Ridiculous’ Reliance

States overseeing their own underground or surface mining operations typically have distinct inspections specific to their mines, which are supplemented with MSHA inspections. The federal agency’s rules establish a regulatory floor, with states having the option to enact more stringent rules or ones tailored specifically to the state’s mining environment.

While MSHA inspections are “thorough” and agency inspectors “are doing what they need to do,” the extra effort by states’ worker-safety personnel is worth taxpayers’ money because “having an additional check and balance at the state level increases the likelihood that inspectors will be there to ensure the laws and regulations are being followed and the lives and health of coal miners are being protected,” Celeste Monforton, a George Washington University professorial lecturer, told Bloomberg BNA.

“I think it’s a ridiculous argument that [state governments] can rely on MSHA because the president just proposed this huge budget cut for the Labor Department, which would directly affect MSHA’s ability to do thorough inspections,” Monforton, a former MSHA policy adviser, said before Congress passed a spending bill to finish out the rest of fiscal 2017.

Others said layering additional inspections at the state level trains more eyes on mine safety, which can’t hurt when trying to keep miners safe. The Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection has “found that more protective regulations have resulted in safer mining conditions without affecting mining operations,” Neil Shader, a department spokesman, told Bloomberg BNA in an email.

Deploying state inspectors also allows states to tailor inspections to potential problems known to them because of better knowledge of particular mines, Eric Heis, Ohio Department of Natural Resources spokesman, told Bloomberg BNA in an email.

MSHA is required to conduct comprehensive inspections, analyzing each piece of equipment and surface area in a coal mine. Ohio’s inspectors have the ability to tailor their inspections to focus on priority high-risk areas—where accidents are more likely to occur—known to the state officials in part because they work closely with the mine’s owner to identify those high-risk areas, Heis said.

Still, the federal inspection regime may be seen by some state legislators as duplicative. “A lot of people are throwing their hands up in the air and saying, ‘Why are you doing [state inspections] when you need to get approval from the feds anyway?’” Del. Mark Zatezalo (R), West Virginia House of Delegates Energy Committee vice chairman, told Bloomberg BNA.

‘Constant’ Presence Cited

Strict statutory or regulatory protections mean little if state and federal worker-safety agencies insufficiently enforce those rules, Nancy Loeb, a clinical assistant professor of law at the Northwestern Pritzker School of Law, told Bloomberg BNA. “If you’re going to do inspections and issue citations but not follow up with enforcement, the inspections don’t do a lot of good to protect the miners,” she said.

"[E]ven before Trump, we had a history of insufficient follow-up on violations of safety regulations in the mines, said Loeb, who teaches energy law.

Bruce Watzman, National Mining Association senior vice president for regulatory affairs, disagreed with both assertions. Federal law requires MSHA to conduct inspections of underground coal mines four times each year and inspect surface coal mines twice annually. “People who don’t work in our industry equate that with four days and two days. But an MSHA inspection is much more pervasive and comprehensive than that,” he said.

In fact, MSHA inspectors can be onsite constantly to satisfy the agency’s statutorily mandated inspections plus additional “targeted” ones the agency deems are necessary.

“It is not uncommon for there to be three or four MSHA inspectors at an underground coal mine every day the mine is producing,” he said. “There is almost a constant presence.”

And as far as lax enforcement is concerned, Watzman said enforcement violations lead to citations, which can sometimes be revolved through corrective action within a day. But if no corrective action is taken MSHA is authorized to shut down that section of the mine that’s not in compliance, he said.

Plus, MSHA currently has more inspectors to conduct federal coal-mine inspections per coal mine in 2016 than it did in 2011, according to Energy Information Administration data. While the number of U.S. coal mines increased 35.6 percent between 2011 and 2016, the number of MSHA coal-mine inspectors decreased relatively less—12.1 percent—meaning MSHA has the resources to put more inspectors more frequently into the nation’s mines, Watzman said.

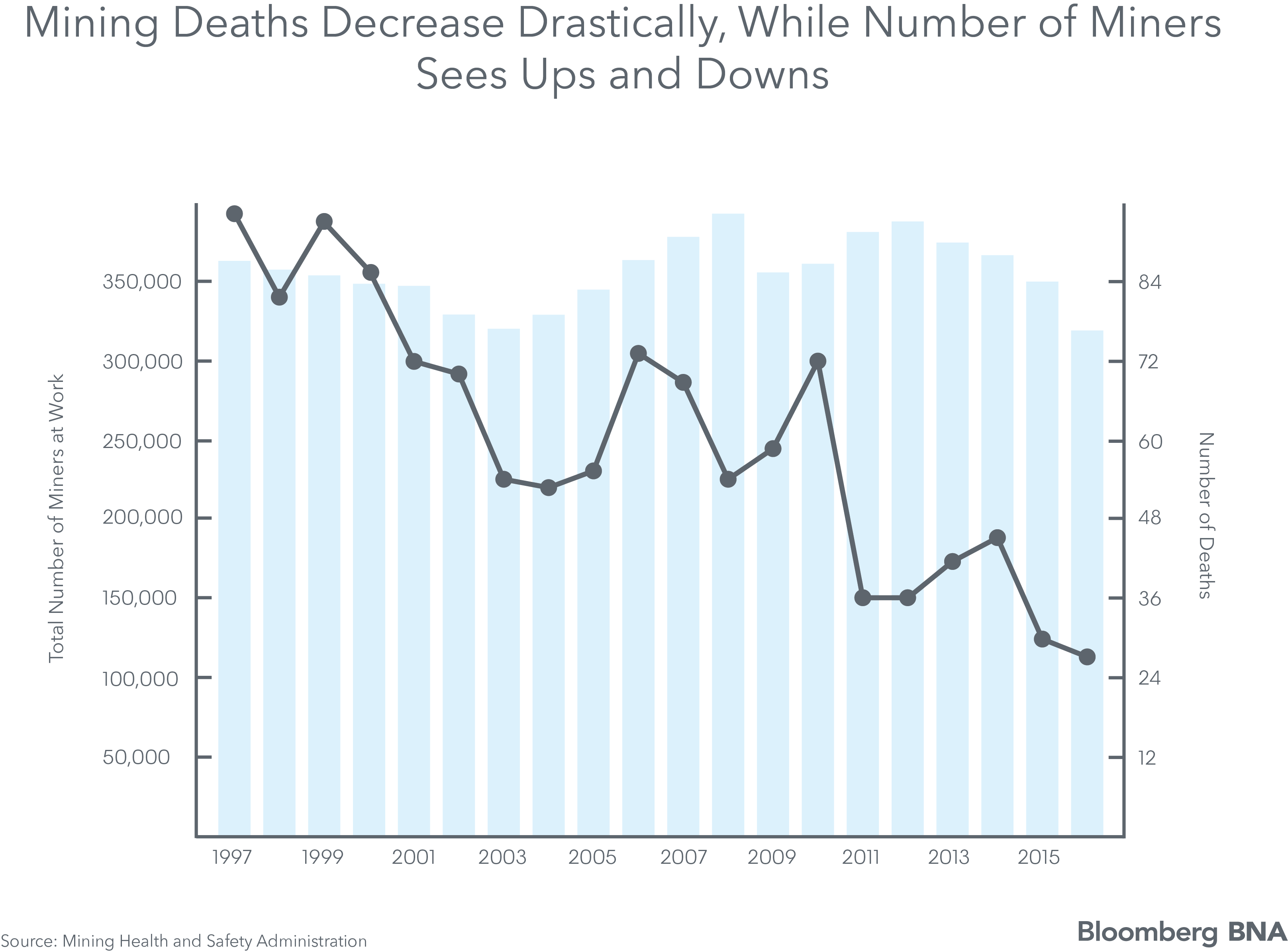

The number of coal-mine fatalities is declining. Fatalities in U.S. coal mines dropped 63.9 percent between 2010 and 2016, a period in which coal mining has declined drastically, according to MSHA data.

Kentucky Legislation

Last month, Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin (R) replaced the state’s Department for Natural Resources required six on-site inspections with a minimum of three on-site inspections each year ( HB 384). Additional required inspections will be replaced by “mine safety analysis” visits.

Rep. Robert Benvenuti (R), a bill sponsor, told Bloomberg BNA the state analyst visits evaluate miner behavior, while the federal MSHA visits focus on a mine’s structural conditions.

Dwindling safety inspections isn’t a new thing for the state, as only four inspections were required over the last two years due to budget constraints.

“It’s going to take our limited dollars and focus them in an evidence-based way instead of simply going down [in the mines] and looking at something a federal inspector might have done the day before,” he said. "[W]hen you have limited dollars, I would suggest to you that you have to get smarter about what you want to do if you want to maintain safety.”

Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet department officials said the law will improve mine safety, and department spokesman John Mura told Bloomberg BNA the analyst visits will enhance, not reduce coal-miner protections.

“We are excited about this opportunity because of all the serious accidents that we have seen in the recent past in Kentucky mines, 94 percent are caused by miner behavior,” Mura said.

Action Compelled by Tragedy

Not everyone is as thrilled.

Mine owners cannot receive citations and associated financial penalties during these visits, reducing the costs associated with noncompliance. And the potential reductions in required site inspections worry people such as Wes Addington, a lawyer at the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center. Addington and others, including state regulators, said interest in enacting or tightening state inspection laws unfortunately only become a priority in the aftermath of a mining disaster. Several pointed to legislative actions taken in Ohio and elsewhere following a mining disaster in Sago, W. Va., in 2006 that killed 12 miners.

“Sadly, the legislature and Gov. Bevin are ignoring the history of coal mine deaths and disasters in this state. Slashing the number of mine inspections will lead to fatalities and catastrophic injuries,” Addington wrote in an email to Bloomberg BNA. “Mining families deserve better.”

“We have seen a continual regression of state mine-safety legislation in Kentucky over the past four to six years, and we think that’s bad for Kentucky coal miners,” Smith of UMWA said.

W. Va. Bill Scuttled

Legislation in West Virginia ( S 582, HB 3029) that would repeal, amend and re-enact a 1931 law in ways that would fundamentally change the state’s worker-safety compliance regime for coal miners never made it out of committee by a legislatively imposed deadline.

The bill proposed to replace mine inspections with “compliance visits” and “safety compliance assistance visits.” The number of required annual site visits was knocked down from four to one. Part of the existing law that allowed for no-advance-notice visits to mines was deleted and a requirement to submit mine ventilation plans to the state was abolished in favor of having MSHA approve them.

“It basically would have removed the state from enforcing mine safety law—left it totally to MSHA,” Patrick McGinley, a West Virginia University College of Law professor, told Bloomberg BNA. “While the state has moved from Democrat blue to Republican red in the last decade, ending up with an endorsement of Donald Trump’s candidacy, West Virginians and the politicians understand that mine safety should not be a partisan issue.”

“Out of nowhere to propose a bill that would end mine safety enforcement by the state regulatory agency, clearly the reaction was very negative to that,” he said.

In its place, legislation was introduced ( S 687) and ultimately signed into law by the state’s governor. It shifted responsibilities among existing boards that oversee the mining industry in an effort to introduce administrative efficiency. It also introduced new health measures when diesel-powered equipment are used in underground coal mines.

The law retains a state inspection regime enforced by the state Office of Miners’ Health Safety and Training, but legislators may change that office’s duties in the future if they conclude regulatory overlap is occurring, Zatezalo said. “At this point in time we didn’t see any reason to eliminate what the state does,” he said.

Already, MSHA inspectors have a significant presence in West Virginia, Zatezalo said.

That is thanks in part to Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.), the state’s former governor. During the Obama administration, Sen. Manchin recommended mine safety improvements to MSHA, and as governor, he created a safety hot line for miners to anonymously report unsafe workplace conditions as well as providing funds for mine safety training.

“Welfare and wellbeing of the miner is the most important thing we have,” Manchin told Bloomberg BNA May 2. “And every good operator will tell you the most valued part of an operation—it’s not the continuous miner [machine], it’s not this machine or that machine—it’s the individual who runs those.”

Manchin said complaints of redundant inspections took away from the miners being able to do their job, but also stressed a balance of inspections could still put safety at the forefront.

“I’ve always been a 10th Amendment [supporter] being a former governor,” he said. “With that being said, we should be held accountable, responsible for the people we represent in our states. So when the federal government comes down, swoops down from Washington, that’s not correct.”

The West Virginia Coal Association did not respond to a Bloomberg BNA request for comment.

Presidential Action

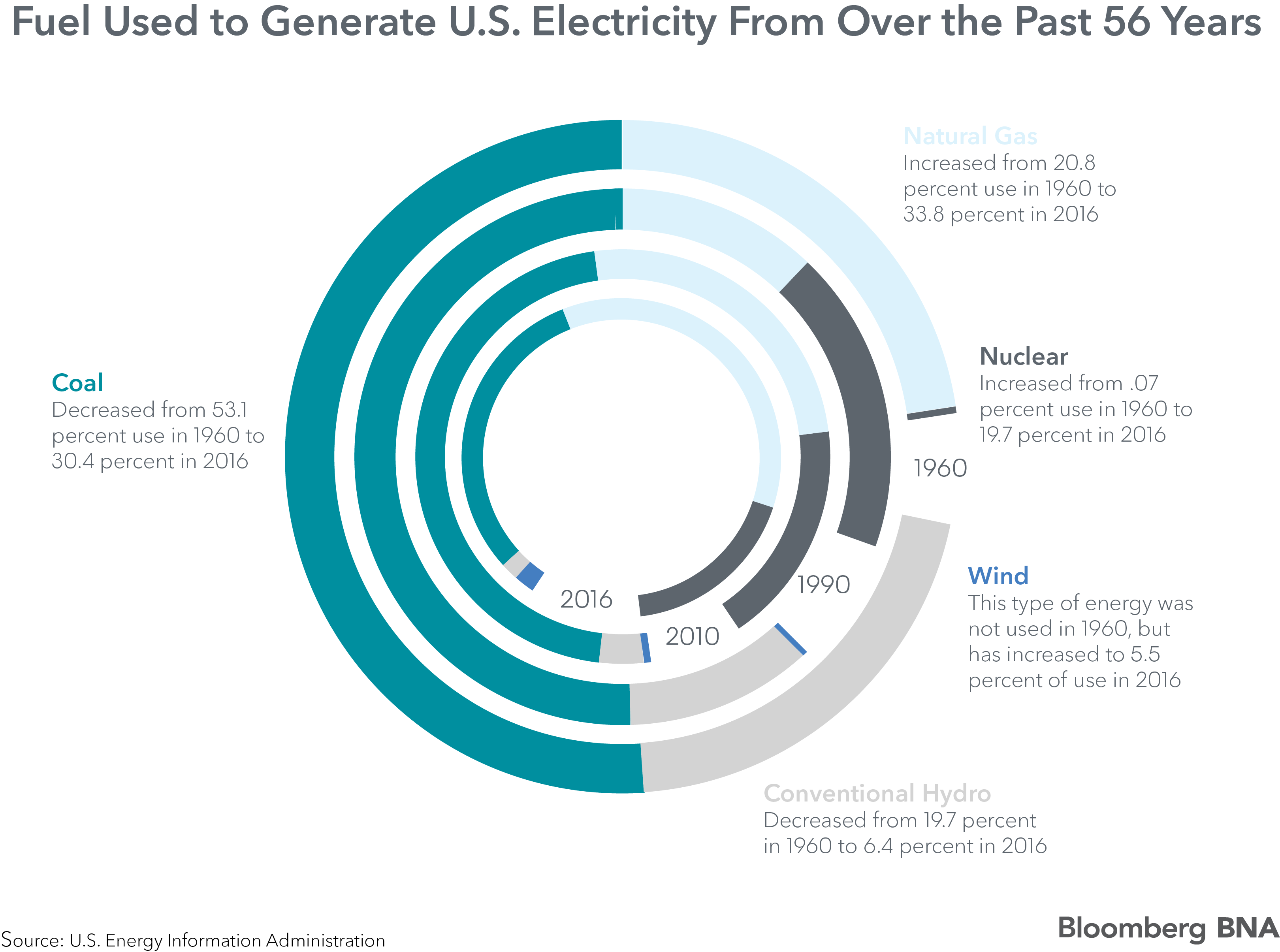

All of these state legislative actions follow Trump’s push to revive the coal industry, in part by working to reduce regulatory burdens on coal-mine owners and increase both coal mining jobs and the amount of coal pulled out of the ground.

Since taking office in January, Trump has tallied several wins to prove he’s serious about reducing the mining industry’s regulatory burden. He nullified an Interior Department’s rule to remove regulatory burden on the coal industry and fuel job creation in February, and signed late last month executive orders allowing the resumption of coal sales from federal land, abolished carbon dioxide limits on coal-fired power plants and eliminated various Obama administration-era rules aimed at mitigating the effects of climate change.

A certain irony accompanies those presidential actions—many of which were carried out as Trump was surrounded by coal miners, Shapiro of Wake Forest Law School said.

“You have to ask, ‘Who is he trying to protect here?’ He claims he is preserving or adding jobs to the coal industry, but at the same time those workers are employed in a very risky job and you’d want to protect them,” said Shapiro, who specializes in administrative procedure and regulatory policy.

If the past is any indicator, the Trump years will be marked by a shift away from strict enforcement actions and toward an environment that favors greater cooperation between regulators and the regulated community on the believe that compliance increases when enforcement is viewed as a partnership, Shapiro said.

“There is always the question in these enforcement regimes of when do you cooperate and when do you punish,” he said.