Dominion Eyeing Coalfields for Hydroelectric Facility

By Carmen Forman

July 2, 2017 - Dominion Energy Inc. is searching for sites in Virginia’s coalfields region to build a hydroelectric facility as a result of a new law that went into effect Saturday.

Bills carried by lawmakers from far Southwest Virginia would fast-track hydroelectric pumped storage facilities in the coalfields by declaring such energy projects in the public interest and allowing electric utilities to petition the state to recover the costs of their investments once a facility is operable.

But the bills by state Sen. Ben Chafin, R-Russell, and Del. Terry Kilgore, R-Scott, start another conversation. The lawmakers pitched building a pumped storage facility in an abandoned coal mine — something that’s never been done before.

Virginia’s coalfields region of Lee, Scott, Buchanan, Wise, Russell, Tazewell and Dickenson counties and Norton have seen dozens of mines shuttered as the coal industry has waned.

Local tax revenue has dwindled and many residents have left in search of jobs elsewhere, a trend that’s predicted to continue for the next two decades.

The bill sailed through Virginia’s General Assembly as a way to bring new tax revenue and jobs to the coalfields.

The coalfields legislators also have suggested a revenue-sharing model so a pumped storage facility in one locality spreads wealth to the rest of the region.

This month, the lawmakers will meet with local boards of supervisors to discuss the benefits of a pumped storage facility and answer any questions they may have, Chafin said.

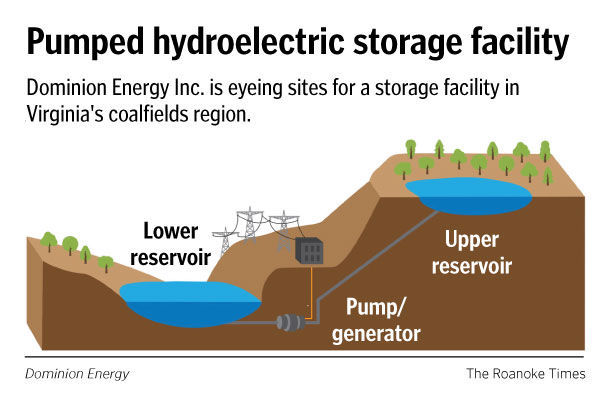

Pumped storage facilities have two separate reservoirs. During peak electricity times, the water flows from the top reservoir to the bottom — powering turbines and creating energy along the way.

During non-peak hours, the water in the bottom reservoir is returned to the top, sometimes with the help of renewable energy sources like wind or solar power.

Usually, the electricity produced at pumped storage facilities is funneled to customers during peak energy times, such as during extremely hot or cold weather.

Appalachian Power Co. operates the dams at Smith Mountain and Leesville lakes, a pumped-storage facility called the Smith Mountain Project that’s been in operation since 1966. Dominion has operated the much larger Bath County Pumped Storage Station since 1985.

In scouting sites for a pumped-storage facility in the coalfields, Dominion representatives are viewing a variety of locations — abandoned coal mines and others, said spokesman David Botkins.

“Everything’s on the table,” he said. “Nothing’s being ruled out. The abandoned coal mine idea is a really interesting one.”

Dominion’s project is in its infancy as the utility company searches for suitable sites.

But Botkins said a pumped storage facility in the coalfields would be smaller than the company’s Bath County facility, which can create 3,000 megawatts of energy — enough to power 750,000 homes.

The project could easily cost upward of $1 billion, Botkins said. That money would, in part, translate to new tax revenue, and construction of the facility would create both temporary and permanent jobs.

But flipping the switch on a new pumped storage facility could be a decade out with all the complexities involved with planning, permitting and construction, Botkins said.

The legislation that went into effect Saturday streamlines the process for a privately owned energy company to receive a public interest designation for a project, Chafin said.

Normally, public interest designations are reserved for publicly owned utilities, he said.

On the federal level, Rep. Morgan Griffith, R-Salem, has filed a related bill that reduces regulations that slow down the permitting process for closed-loop pumped storage facilities.

Essentially, Griffith’s bill cuts the water studies required for open-loop pumped storage facilities because they are connected to naturally flowing water sources.

Closed-loop facilities haul in water instead of interfering with local water sources, making such environmental regulations unnecessary, Griffith said.

Anything the federal government can do to reduce nonessential regulations and costs on these pumped storage projects, the more likely it is that they will come to fruition, Griffith said.

“The bottom line is … we’re taking an asset that’s sitting there, infrastructure that’s sitting there unused and turning it into a positive for the community,” he said.

About a year ago, the coalfields delegation had a brainstorming session to come up with ideas that could be game-changers for the struggling region.

That’s when the lawmakers decided to stick to with energy production — what Southwest Virginia does best, Chafin said.

“We feel the people of the region have for a good many years understood how to produce energy and how to produce raw material to create energy with, so we just feel like this is going to be a really good fit,” he said. “We hope to see one or more of these built.”

Rough estimates suggest building a hydroelectric facility could create about 1,000 construction jobs during the multiyear process and about 50 permanent jobs, Chafin said.

Dominion also opened the Virginia City Hybrid Energy Center in Wise County in 2012, which has a net generating capacity of 600 megawatts of electricity, mostly through burning coal but with 20 percent from biomass fuel.

Unlike Dominion, Appalachian Power Co. has no current plans to build a new pumped storage facility, said company spokesman John Shepelwich.

Appalachian Power is experiencing relatively flat growth and isn’t in need of the amount of energy a pumped storage facility would provide, he said.

“From our point of view, certainly we would encourage anything that would help develop the economy in the coalfields area,” he said. “But at this point, we’re not looking at that kind of development.”