Under Trump, Coal Mining Gets New Life on U.S. Lands

By Eric Lipton and Barry Meier

August 7, 2017 - The Trump administration is wading into one of the oldest and most contentious debates in the West by encouraging more coal mining on lands owned by the federal government. It is part of an aggressive push to both invigorate the struggling American coal industry and more broadly exploit commercial opportunities on public lands.

The intervention has roiled conservationists and many Democrats, exposing deep divisions about how best to manage the 643 million acres of federally owned land — most of which is in the West — an area more than six times the size of California. Not since the so-called Sagebrush Rebellion during the Reagan administration have companies and individuals with economic interests in the lands, mining companies among them, held such a strong upper hand.

Clouds of dust blew across the horizon one recent summer evening as a crane taller than the Statue of Liberty ripped apart walls of a canyon dug deep into the public lands here in the Powder River Basin, the nation’s most productive coal mining region. The mine pushes right up against a reservoir, exposing the kind of conflicts and concerns the new approach has sparked.

“If we don’t have good water, we can’t do anything,” said Art Hayes, a cattle rancher who worries that more mining would foul a supply that generations of ranchers have relied upon.

During the Obama administration, the Interior Department seized on the issue of climate change and temporarily banned new coal leases on public lands as it examined the consequences for the environment. The Obama administration also drew protests from major mining companies by ordering them to pay higher royalties to the government.

President Trump, along with roundly questioning climate change, has moved quickly to wipe out those measures with the support of coal companies and other commercial interests. Separately, Mr. Trump’s Interior Department is drawing up plans to reduce wilderness and historic areas that are now protected as national monuments, creating even more opportunities for profit.

Richard Reavey, the head of government relations for Cloud Peak Energy, which operates a strip mine here that sends coal to the Midwest and increasingly to coal-burning power plants in Asia said Mr. Trump’s change of course was meant to correct wrongs of the past.

The Obama administration, he said, had become intent on killing the coal industry, and had used federal lands as a cudgel to restrict exports. The only avenues of growth currently, given the shutdown of so many coal-burning power plants in the United States, are markets overseas.

“Their goal, in collusion with the environmentalists, was to drive us out of the export business,” Mr. Reavey said.

Even with the moves so far, the prospect of coal companies operating in a big way on federal land — and for any major job growth — is dim, in part because environmentalists have blocked construction of a coal export terminal, and there is limited capacity at the port the companies use in Vancouver.

Competition from other global suppliers offering coal to Asian power plants is also intense.

But at least for now, coal production and exports are rising in the Powder River Basin after a major decline last year.

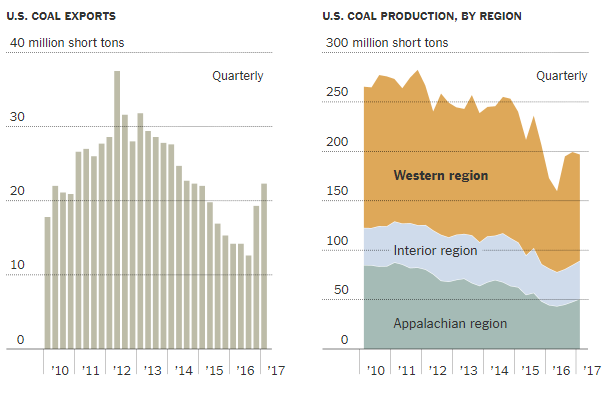

Western Coal

The majority of United States coal is produced in the West, with a small share of it then exported. About 85 percent of coal extracted from federal lands comes from the Powder River Basin, in Wyoming and Montana. The Trump administration is rolling back an Obama-era moratorium on new coal leases on federal lands.

Note: The Appalachian region includes Alabama, eastern Kentucky, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia. The interior region includes Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, western Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma and Texas. The Western region includes Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Utah and Wyoming.

Source: Energy Information Administration.

Opponents of the Trump administration’s direction have already gone to court. New Mexico and California sued in April to undo the rollback in royalties that coal mines pay, while ranchers like Mr. Hayes and the Cheyenne tribe joined a lawsuit in March challenging the repeal of a year-old moratorium on federal coal leasing.

“If we hand over control of these lands to a narrow range of special interests, we lose an iconic part of the country — and the West’s identity,” said Chris Saeger, executive director of the Montana-based environmental group Western Values Project, referring to coal mining and oil and gas drilling that the Interior Department is moving to rapidly expand.

Mr. Trump’s point man is Ryan Zinke, a native Montanan who rode a horse to work on his first day as head of the Interior Department. A former member of the Navy SEALs and Republican congressman, Mr. Zinke oversees the national park system, as well as the Bureau of Land Management, which controls 250 million acres nationwide, parts of which are used to produce oil, gas, coal, lumber and hay.

In late June, Mr. Zinke visited Whitefish, Mont., to attend a meeting of Western governors, where he vowed to find a balance between extracting commodities from federal lands and protecting them.

Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, left, with Bill Cadman of Whiting Petroleum in Whitefish, Mont., in June. “We are all affected by this constant regulatory quagmire,” Mr. Cadman said.

Photo by Tim Goessman for the New York Times

“Our greatest treasures are public lands,” Mr. Zinke said in a speech. “It is not a partisan issue. It is an American issue.”

Afterward, protesters from the Sierra Club and other groups held a rally in the town square against the actions taken by Mr. Zinke during his first months on the job, chanting “Shame!” and “Liar!” and carrying signs opposing his policies.

But Mr. Zinke was not in public view. Just before the rally started, he was inside a nearby building, meeting with Bill Cadman, a vice president of Whiting Petroleum, a company that drills on federal lands.

Until recently a state legislator in Colorado, Mr. Cadman has lobbied the Interior Department to repeal a rule that limits methane emissions from oil and gas sites on federal land. As he left the brief gathering, Mr. Cadman said he was only catching up with Mr. Zinke, whom he has known for decades, on family-related matters. He also acknowledged that Mr. Zinke wielded a lot of power over the energy industry.

“We are all affected by this constant regulatory quagmire,” Mr. Cadman said.

Seeing a Liberal Attack

Cloud Peak Energy had been preparing for several years to seize upon the arrival of an industry-friendly administration in Washington. But it was also prepared to fight without one.

At a gathering of a coal industry trade group in 2015, Mr. Reavey, the company’s chief lobbyist, left no doubts about the company’s determination to defend mining in the Powder River Basin, which includes operations here in Decker.

Mr. Reavey likened the industry’s existential crisis to that of tobacco companies in the 1990s. The coal industry, he told executives, had been targeted by a liberal conspiracy of environmental groups, news organizations and regulators. Coal would suffer the same fate as cigarettes, he warned, unless the industry stood its ground.

He showed a PowerPoint slide that outlined the strategy of the industry’s opponents. They sought to diminish coal’s “social acceptability,” the slide showed, while also cutting “profits through massive increase in regulation” and reduced “demand/market access.” He equated the situation to a scene in the film “Independence Day” in which the American president asks the alien invaders, “What is it you want us to do?” An alien replies, “Die.”

During President Barack Obama’s second term, the coal industry’s chief antagonist was Sally Jewell, a former oil industry engineer appointed Interior secretary in 2013. Ms. Jewell, an avid hiker, had also served as chief executive of the outdoor gear company REI.

She saw mining companies as a particular problem because they too often left behind polluted mine pits and paid too little for coal leases on federal land.

Starting two years ago, Ms. Jewell took a series of steps to change the relationship between coal companies and the federal government. She imposed a moratorium on new federal coal leases while beginning a three-year study of the industry’s environmental consequences. More than 40 percent of all coal mined in the United States comes from federal land, and when burned it generates roughly 10 percent of the country’s total greenhouse gas emissions.

In addition, she called for greater transparency in the awarding of coal leases, and she backed an increase in the royalty payments made to operate coal mines on public lands.

“The corruption in the coal sector is just so rampant,” she said in an interview.

A central problem, she said, was the lack of competitive bidding for mining leases: Only 11 of the 107 sales of federal coal leases between 1990 and 2012 received more than one bid, according to a report by the Government Accountability Office. A second study, by a nonprofit think tank, estimated that the practice had shortchanged taxpayers tens of billions of dollars.

Another hot-button issue was how much to charge in royalties, which generate about $1 billion a year for the federal government.

Under federal rules adopted in 1920, coal companies are required to pay “not less than” 12.5 percent on sales of surface coal mined on federal lands. But for years, studies indicate, the companies paid far less — as little as 2.5 percent of the ultimate sale price — because they often negotiated large royalty discounts with sympathetic federal officials. Companies also often sell coal first to a corporate affiliate at a sharply reduced price, before reselling it to the intended customer, costing the government a chunk of its royalties, according to the Government Accountability Office study. The technique was particularly popular among mines with foreign buyers.

Mining operations in 2014 in the Powder River Basin, the nation’s most productive coal mining region.

By Bruce Gordon, Ecoflight

To eliminate the loophole, the Interior Department adopted a rule last year requiring that the payment be calculated on the first arm’s length transaction, meaning sales to corporate affiliates would not count. Such a change would be a blow to the bottom lines of companies mining in the Powder River Basin, which accounts for about 85 percent of all coal extracted from federal lands, with a growing share headed to Asia.

The coal industry was bent on killing the rule, sending executives to plead its case to the White House and filing a federal lawsuit to block it. “They are liars, and they know it,” Mr. Reavey, the Cloud Peak lobbyist, said of those who suggested the industry was not paying its fair share in royalties.

Mr. Zinke, then a freshman congressman from Montana, stepped up as an important industry ally, trying unsuccessfully to derail the rule on at least four occasions. He raised objections during a budget hearing with Ms. Jewell at the witness table, signed two letters in opposition and sought to introduce language in a House appropriations bill to prohibit the agency from enforcing the rule.

The alliance between Mr. Zinke and the coal industry is well documented in his campaign finance disclosures.

Elected to the House in 2014, Mr. Zinke received $14,000 in campaign donations from the company that owns BNSF Railway, the chief transporter of coal in the Powder River Basin, as well as a total of $26,000 from Cloud Peak, Arch Coal and Alpha Natural Resources, three of the nation’s largest coal companies. Several of the donations arrived just as Mr. Zinke pushed in Congress to block the new royalty rule, campaign finance records show.

Finishing the Job

What Representative Zinke started, Secretary Zinke and his team were poised to finish.

In February, even before the Senate confirmed Mr. Zinke to his new post, Mr. Reavey of Cloud Peak was meeting at the Interior Department headquarters in Washington with President Trump’s political appointees. Among them was Kathy Benedetto, who was temporarily overseeing the division in charge of coal leases.

“We made clear that we thought this rule was bad and they had an opportunity to stop this process from going forward,” he said of the change in royalty payments.

Cloud Peak and other mining industry giants also put their objections in writing, asking the department to delay the rule until the industry’s lawsuit was resolved. Within days, they got their wish. The agency, reversing its position during the Obama presidency, froze the rule and told Cloud Peak and other industry lawyers that they had “raised legitimate questions.”

By late March, after Mr. Zinke was sworn in, the rollback continued. Mr. Zinke repealed Ms. Jewell’s moratorium on new coal leases, and canceled further work on the study she had ordered. The first part — 1,378 pages examining 306 active federal coal leases — had been issued in January.

“Costly and unnecessary,” Mr. Zinke said in announcing that the study was, in essence, being thrown in the trash.

The decisions caused an uproar among Democrats in Washington, but the tensions they unleashed were also on display this summer at an extreme sporting event on the Crow Indian reservation, not far from the coal mines here in Decker.

Hundreds of people, including members of both the Crow and neighboring Cheyenne tribes, had gathered for an annual competition known as the Ultimate Warrior. The event consists of a mile run to a river, a mile of canoeing, seven more miles of running and then a nine-mile bareback horse race.

Cloud Peak is a sponsor of the event. In 2013, the Crow had signed an agreement giving the company the right to extract up to 1.4 billion tons of coal on the tribe’s lands. The industry-friendly approach of the Trump administration had leaders feeling optimistic that Cloud Peak would move forward, as the project still needs many permits from the federal government.

The tribe estimates the Cloud Peak operations could generate $10 million in payments for a community where the unemployment rate in June was 19.4 percent, five times the state average. “Coal, for us, is the ticket to prosperity,” said Shawn Backbone, the tribe’s vice secretary, who attended the warrior competition. “We are rich in coal reserves. But we are cash poor.”

But the Cheyenne are not happy. They have historically opposed coal mining and worry Cloud Peak’s expansion would irrevocably damage the environment. They have joined the lawsuit by the nearby rancher, Mr. Hayes, challenging the decision to lift the moratorium on new coal leases.

“We are wealthy in life here,” said Donna Fisher, a Cheyenne who lives along the Tongue River and who attended the warrior competition with her grandson. “We don’t have money. But we have land, water and air. Snuff that out and we are gone.”

Friends in High Places

As he walked on stage at the governor’s gathering in Whitefish, Mr. Zinke exuded confidence. The United States, he argued, can and should expand energy production from its federal lands, with money earned from leases going toward repairs to roads and bridges, and at national parks.

“As Interior secretary, I am looking at both sides of our balance sheet,” Mr. Zinke said. “There is a consequence of not using some of our public land for the creation of wealth and jobs.”

It was a decidedly familiar venue, and Mr. Zinke was relaxed. Whitefish is where he played guard on the high school football team and where as a Boy Scout he had built a rope-and-pole footbridge over the river.

“I think I am probably the only person who has played trombone on this stage,” he joked in his opening remarks.

The top sponsors of the event were familiar, too. They included Anadarko Petroleum and BP, oil and gas companies, as well as Barrick Gold and Newmont, mining companies. BNSF, the railroad, was also represented, as were major coal-burning utilities like Southern Company.

Most of them had a keen interest in the Interior Department and Mr. Zinke’s new stewardship of it. Barrick’s Cortez mine, for example, has a pending application to expand open pit mining in Nevada, while Newmont is seeking approval for the environmental cleanup of a Nevada mine.

Conrad Anker, a mountaineer and author, took the stage after Mr. Zinke. He said in an interview that organizers had instructed him not to mention climate change, or its effect on the glaciers at Glacier National Park. According to a federal study, the glaciers have lost as much as 85 percent of their mass over the past 50 years.

There was no such restraint on the nearby town square, where protesters flashed signs with slogans like “Zinke Sells Soul to Big Oil” and “What Would Teddy Do?” — a reference to Mr. Zinke’s statements that he admired President Theodore Roosevelt, a conservationist who helped set aside millions of acres as public land.

Next to the square, at a pizza restaurant, a once-powerful Washington couple reflected on the frustration of those opposed to the administration’s new direction.

Jennifer Palmieri, a senior adviser in the Obama White House and later a top campaign aide to Hillary Clinton, was eating with her husband, Jim Lyons, an Interior official during Mr. Obama’s second term.

Both had expected senior administration roles had Mrs. Clinton won. Now, Mr. Lyons was in Whitefish trying to salvage the rules on oil, gas and coal that he had helped develop just a few years ago. He was holding sessions with governors hoping to enlist them to pressure Mr. Zinke and others.

“Instead of driving change, we are searching for ways to continue to be an influence,” Mr. Lyons said. “Frustration is an understatement.”