Trump Promised to Put Coal Miners Back to Work. Kentucky has Fewer Coal Jobs Now.

By Bill Estep

November 11, 2018 - Two years since Donald Trump carried every Kentucky coal county by whopping margins after promising miners would go back to work if he became president, the state has fewer coal jobs.

Coal employment averaged 6,550 in Kentucky in the first quarter of 2017 when Trump was sworn in, according to the state Energy and Environment Cabinet.

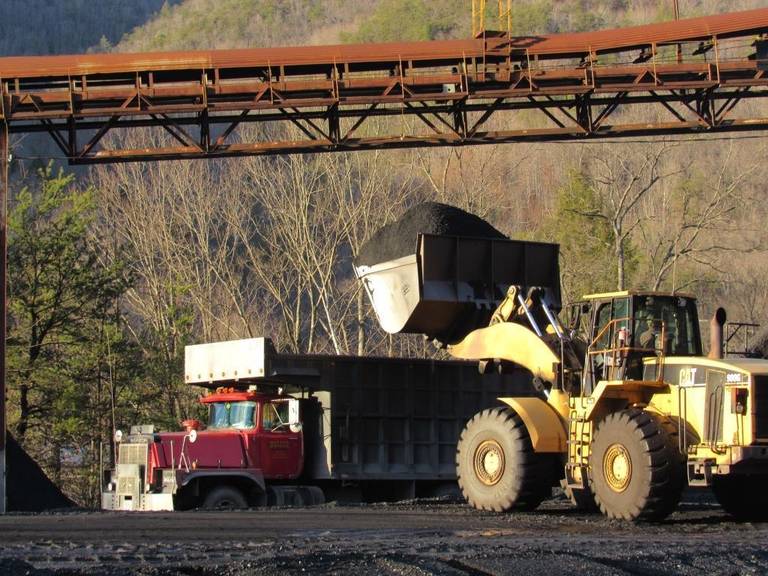

A worker uses a large front-end loader to scoop coal from a pile near where it was mined in Harlan County and puts it into a truck to be taken to a rail-loading facility.

Photo by Bill Estep

The estimated average in the July-through-September quarter this year was 6,381, according to a cabinet report released this week.

Of those jobs, 3,851 were in Eastern Kentucky and 2,530 were in the state’s western coalfield. Both regions had fewer jobs than in early 2017.

Production also slowed in the third quarter.

The number of coal jobs varies from quarter to quarter in Kentucky and has been higher at times since Trump took office. The picture is mixed among counties, with some having more jobs and others less than when Trump took office.

But overall, the numbers show there has been no sustained increase in coal employment in the state. Coal jobs in Kentucky topped 18,000 in 2011.

“It ain’t happened like they said it would,” said Martin County Judge-Executive Kelly Callaham.

Callaham said one mine has recently hired some people in the county. Employment in the most recent quarter stood at 61, compared to more than 200 in early 2017, according to state records.

Nationally, there were about 1,900 more coal jobs In October than when Trump took office, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

One reason Kentucky has not shared in the growth is that the state has relatively little coal of the type used in making steel, called metallurgical coal, which has been in demand overseas.

West Virginia has more metallurgical coal, so has seen a pick-up in mining jobs.

However, the estimated national total of 52,600 coal jobs in October was far below the most recent peak of nearly 90,000 in late 2011.

The latest report on Kentucky coal employment and production indicates that the staggering job losses that began in 2012 have stopped.

Coal jobs in Eastern Kentucky plummeted by 29 percent in 2012 and another 23 percent in 2013. Western Kentucky didn’t see such dramatic losses at the beginning of the downturn, but in 2015, when Eastern Kentucky saw another 29 percent annual job loss, employment slumped by 24.9 percent in Western Kentucky.

By comparison, employment in Eastern Kentucky in the third quarter was down 6.4 percent from a year earlier and 2.8 percent from the second quarter.

Western Kentucky saw an employment gain of 8.5 percent in the most recent three months, boosting overall state employment 1.4 percent above the second quarter.

Statewide, jobs were down 4.2 percent from the same time in 2017.

Employment has been stable between 6,300 and 6,600 jobs since mid-2016, according to the cabinet’s reports.

“We feel that the blood-letting that was happening as recently as 2016 has ceased,” said Tyler White, president of the Kentucky Coal Association. “We’re doing a lot better.”

That has put the industry on a more even keel and boosted optimism, White said.

The industry credits Trump for stopping the big job losses.

Trump rolled back Obama Administration environmental initiatives, including a plan to cut carbon emissions that would have been difficult for many coal-fired power plants to meet.

Many in the industry believe that if Trump hadn’t been elected, the free-fall would have continued.

“I think that we definitely would’ve gone done further,” White said.

Projections of future coal production don’t portend a significant increase in jobs in Eastern Kentucky.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration projects that production will gradually decline through 2040 in Central Appalachia, the region that includes Eastern Kentucky.

The agency projects production will go up in the region that includes Western Kentucky, however.

Competition from natural gas for power-plant customers has hurt coal in Kentucky and elsewhere.

In a recent news release, EIA projected the share of electricity generated by utilities using gas will go up from 32 percent in 2017 to 36 percent in 2019, while the share from coal, which was 30 percent in 2017, will drop to 26 percent in 2019.

Studies have concluded that while tougher environmental rules and the rise of renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar power, pushed down coal use, relatively cheap, cleaner-burning natural gas has been the biggest factor in the decline.