Alabama Climate Change Skeptic Named to Trump's EPA Advisory Board

February 1, 2019 - The Trump administration continued its reshaping of how science is evaluated at the Environmental Protection Agency with the appointment Thursday of a slew of new members to a key advisory panel.

Among the eight additions to the agency's Science Advisory Board are a number of members whose ideas run against mainstream scientific thinking on issues that include the health effects of radiation and the modeling of Earth's climate.

Andrew Wheeler, the acting EPA chief, added the eight new members while reinstalling eight others selected during the Obama administration. He cast the appointments as a reaffirmation of the Trump administration's commitment to hearing scientific opinions from a diverse set of voices.

"In a fair, open, and transparent fashion, EPA reviewed hundreds of qualified applicants nominated for this committee," Wheeler said in a statement. "Members who will be appointed or reappointed include experts from a wide variety of scientific disciplines who reflect the geographic diversity needed to represent all ten EPA regions."

But critics of the administration see this and other moves under Wheeler and former EPA chief Scott Pruitt as part of a larger push to make the agency's decisions more friendly to industry.

"The general makeup of the Science Advisory Board has changed significantly in the past two years," said Genna Reed, a science and policy analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists. "What we're seeing is a decrease in the number of academics and a surge in the number of industry and consulting-firm members."

With the announcement Thursday, 26 of the board's 45 members have been appointed by the Trump administration.

The best-known new member of the panel, though, actually does work at a university. John Christy, a professor of atmospheric science at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, is perhaps the most prominent climate skeptic in all of academia.

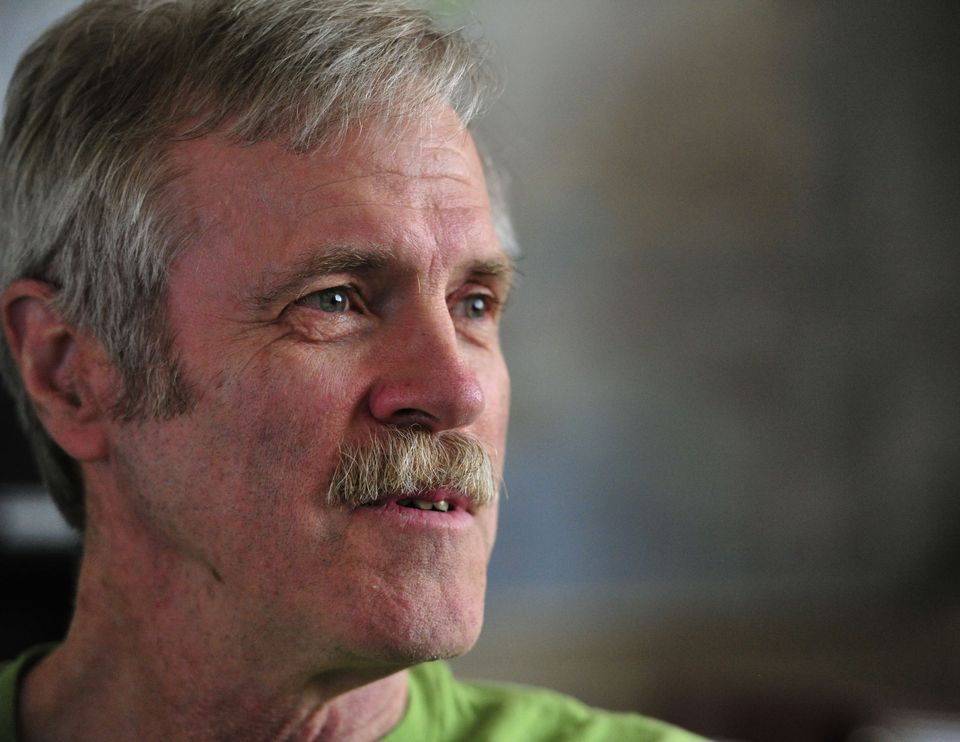

Dr. John Christy, Professor of Atmospheric Science and Director of the Earth System Science Center at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, in his office in Huntsville Tuesday, March 17, 2015.

Photo by Eric Schultz, al.com

Christy acknowledges that humans have altered Earth's climate. But he's a polarizing figure within the climate science community for his criticism of mainstream climate models produced by NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and of scientific conclusions about the severity of global warming reached by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Pointing to his own analyses of satellite temperature data, which suggest that observed warming is on the lower side of projections, Christy has argued that atmospheric temperatures are less sensitive to the buildup of greenhouse gases than the majority of other climate scientists say they are.

Among the many scientific institutions that say global warming is dangerous is the EPA itself. In President Barack Obama's first year in office, the EPA determined greenhouse gases posed a risk to public health, giving the government the legal justification it needed to try to curb emissions from cars, coal plants and other sources.

Christy, Alabama’s state climatologist, takes issue with EPA’s “endangerment finding.”

"I, as well as many others, am very skeptical of the basis of many of these findings, like the endangerment finding," Christy said in an interview Thursday.

He said he believes the EPA's reliance on what he regards as faulty climate models have led it to issue misguided rules for polluters. "If you use bad models," he said, "you're likely to come up with bad regulations."

Christy is often called on by Republicans leery of government climate regulations to testify before Congress. At a 2015 House Science Committee hearing, Christy described the study of climate change as a "murky" science. "We do not have laboratory methods of testing our hypotheses as many other sciences do," he said in his written remarks. "As a result, what passes for science includes opinion, arguments-from-authority, dramatic news releases, and fuzzy notions of consensus generated by preselected groups."

Michael Mann, a climatologist at Pennsylvania State University who has testified opposite Christy before lawmakers, has argued that Christy's findings have become "a central pillar in the case for climate change denial" despite the fact they have "been shown to be an artifact of faulty computations."

The advisory board will also now include Brant Ulsh, a health physicist at M.H. Chew & Associates whose work focuses on low-dose radiation.

In the past, the EPA has maintained there is some risk of cancer from any exposure to radiation. But Ulsh argues the way the government has modeled the health effects of small amounts of radiation exposure at places like nuclear power plants overplays that risk.

"Right now we spend an enormous effort trying to minimize low doses," Ulsh told the Associated Press last year. "Instead, let's spend the resources on minimizing the effect of a really big event."

Another new panelist is Richard Williams, an independent consultant and former Food and Drug Administration official who has praised the Trump administration for cutting regulations.

In the fall of 2017, Pruitt upended the agency's key advisory groups, announcing plans to jettison scientists who have received EPA grants.

The move set in motion a potentially fundamental shift, one that could change the scientific and technical advice that historically has guided the agency as it crafts environmental regulations.

"It is very, very important to ensure independence, to ensure that we're getting advice and counsel independent of the EPA," Pruitt told reporters at the time.

He estimated that the members of three different committees - the Scientific Advisory Board, the Clean Air Science Advisory Committee and the Board of Scientific Counselors - had collectively accepted $77 million in EPA grants over the past three years. He noted that researchers would have the option of ending their grant or continuing to advise EPA, "but they can't do both."

Some former advisory board members sued the agency, calling the new policy "unlawful, arbitrary and capricious." They argued that Pruitt did not have authority to change the agency's ethics rules.

Robyn Wilson, a professor at Ohio State University and one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit, told The Post at the time that as a first-time EPA grant recipient whose term on the agency's Scientific Advisory Board was cut short, she viewed the policy change as "morally reprehensible."

"It all sounds very well intentioned, wanting more diversity on the boards, wanting more voices to be heard. Who is going to disagree with that?" Wilson said then. "But I think it is an attempt to get rid of people who they assume are not on board with the current administration's goals, which are deregulatory."

Wheeler reaffirmed that his new appointees will remain "financially independent" from EPA grants. But he did differ from his predecessor in one way by reupping the terms of Obama-era members.

“It’s a nice departure from the Pruitt administration,” Reed of the Union of Concerned Scientists said. “It’s good to see that Wheeler is acknowledging the value of institutional knowledge on these advisory boards.”