Coal Giants Announce Powder River Basin Deal; Company Doesn't Expect Miner Layoffs

By Brandon Foster and Nick Reynolds

June 21, 2019 - Peabody Energy and Arch Coal will combine their mining operations in the Powder River Basin and Colorado, the companies announced Wednesday morning, bringing together the two biggest coal mines in the country.

While the companies expect the joint venture to save about $120 million annually over the next decade, a Peabody spokesman said the company doesn’t expect the savings to come at the cost of miners’ jobs.

The move combines the North Antelope Rochelle and Black Thunder mines, owned by Peabody and Arch respectively, into a single complex. The Campbell County mines are already the two largest coal mines in the U.S. by production, figures show.

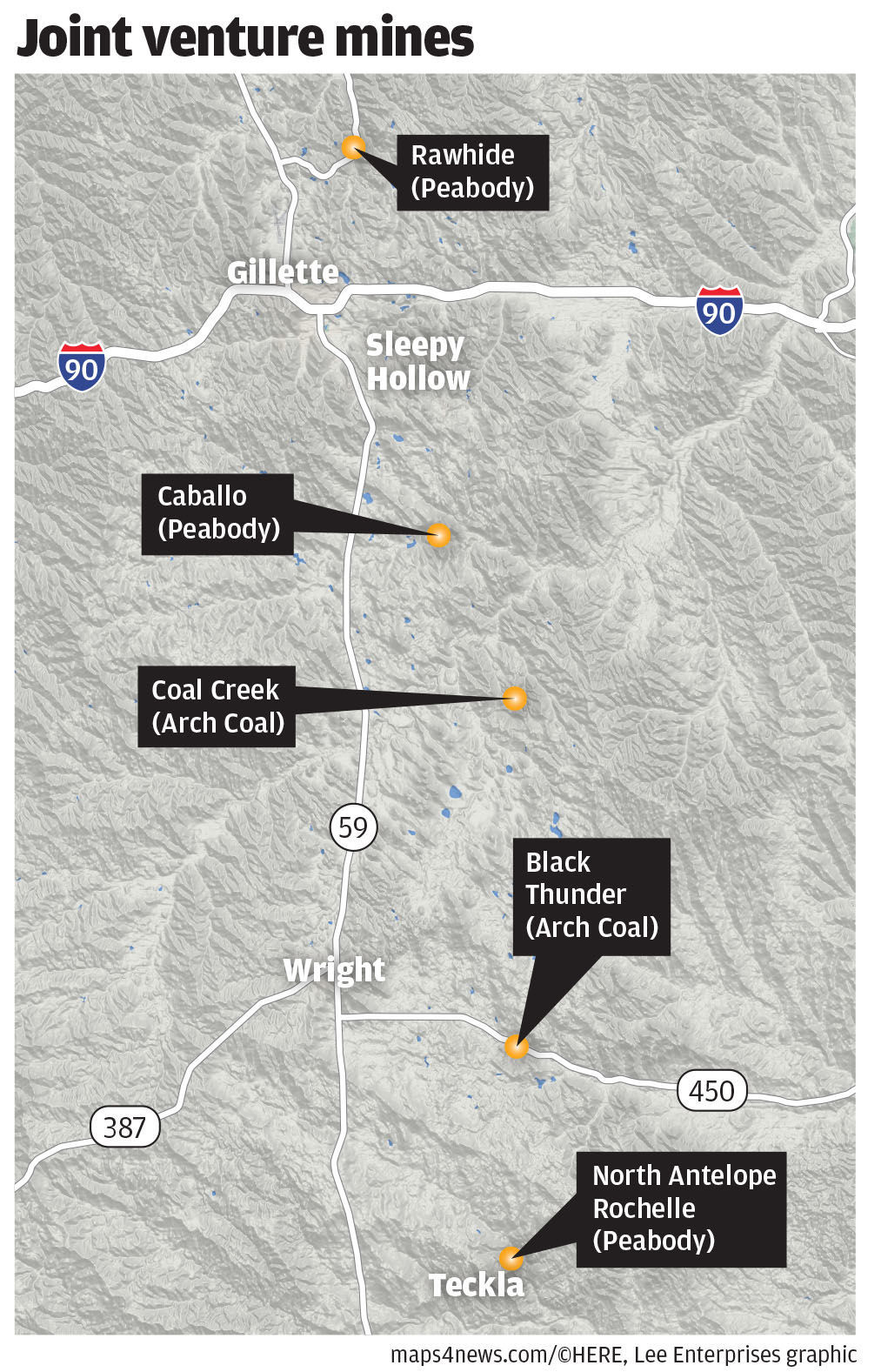

The venture will also involve the Caballo (Peabody), Rawhide (Peabody) and Coal Creek (Arch) mines in the Powder River Basin and the West Elk Mine (Arch) and Twentymile (Peabody) mines in Colorado. The mines in the basin represent mines with five of the 10 highest rates of production in the country, according to a Peabody spokesman.

Arch-Peabody joint venture mines map

Peabody will own 66.5 percent of the joint venture, and Arch will own 33.5 percent. Peabody will manage all activities, including the marketing of coal, according to the announcement.

Both announcements specifically noted natural gas and renewables as reasons for needing to make coal more competitive. A five-member board will manage the venture, with three members appointed by Peabody and two by Arch. Both companies are headquartered in St. Louis.

The company predicts the move will create a net present value of approximately $820 million. In a conference call Wednesday, Peabody President and CEO Glenn Kellow said he expects the majority of savings to be operational. Kellow said the transaction still faces regulatory approval and expects a “multi-month process” before it closes.

Neither Kellow nor Arch CEO John W. Eaves, who spoke on a separate Arch conference call Wednesday morning, said how the move will affect employment numbers. The mines employed about 3,300 workers in 2018.

Eaves did say on the call that the two companies could pursue further cost savings in the future.

“It’s a significant list, and the JV will be intent on finding further opportunities for efficiency gains, cost savings and other value creation,” Eaves said.

However, a spokesperson for Peabody told the Star-Tribune on Wednesday morning that the anticipated cost savings will come not from reduced staffing levels but from reduced overhead. With similar salary and benefits packages between the two companies, the effects felt by the employees themselves will be minimal, Peabody spokeswoman Charlene Murdock said.

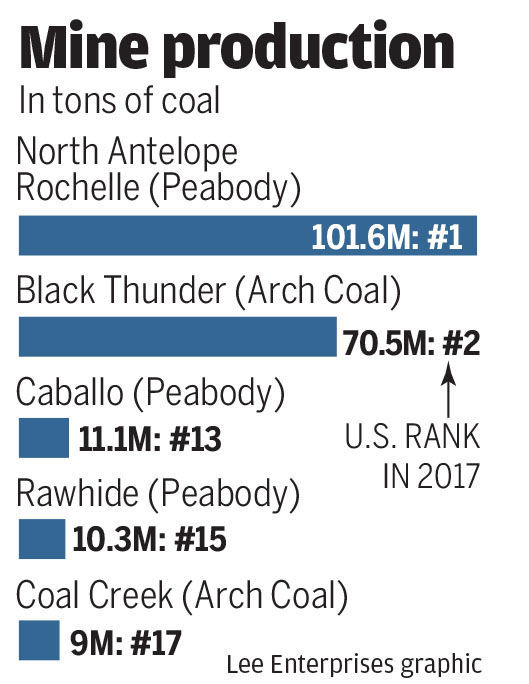

Coal mine production rankings chart

“All things being equal, we expect the hourly workforce to remain constant and only possibly minor changes in the salaried staffing levels,” Murdock said. “Potential opportunities outside of the joint venture may also open up for employees once the agreement is finalized. The fact is, both companies have talented workforces and we will work to preserve that pool.”

“We are committed to communicating openly with our workforce and treating employees fairly,” she added.

Pressure from Gas, Renewables

The announcement comes at a time of intense market pressure for the coal industry, which has been in decline over the past decade amid increased demand for oil and gas and blossoming demand for subsidized energy from renewable sources. In rationalizing the deal, both CEOs said the joint venture will allow the two companies to decrease operating costs to a level where coal could compete on a more equal footing with increasing competition from other energy sources.

The companies say the move creates benefits such as: “improved efficiencies in deployment of the combined equipment fleet,” “enhanced blending capabilities,” “rail efficiencies” and “reductions in long-term capital requirements.”

Wednesday’s announcement was met with optimism by the Wyoming Mining Association’s Travis Deti, who saw the announcement as a sign of a resurgence in competitiveness for the two companies in the face of otherwise diminishing prospects for coal around the world.

“This is big news,” Deti said. “It shows these operators up there in the basin are aggressively adapting to a very changed market environment. This particular exercise is going to take a while to take effect, but the intent is to make the thermal coal industry in Wyoming a little more competitive, bring some costs down and keep the industry alive and going.

“It’s showing these companies are in it for the long haul and they’re fighting to remain competitive,” he added.

Strategically, the deal marks a unique option unavailable to many other Wyoming producers, which have fought to keep their mines financially stable in the wake of shifting market forces. Very rarely, Murdock said, do opportunities arise in which major coal companies can share services to reduce their operating costs, which in turn puts the two companies in a uniquely competitive position that they feel can only improve their prospects.

The announcement yielded a positive response from Wall Street immediately following the announcement, with Arch Coal seeing a sharp increase in their stock price at the opening bell Wednesday while Peabody enjoyed a slight increase in their stock prices. However, long-term prospects for coal, writ large, remain bleak. In a statement Wednesday, Moody’s lead U.S. coal analyst Benjamin Nelson said that while Peabody and Arch Coal’s decision to form a joint venture in the Powder River Basin will “strengthen their business position and is credit positive,” the demand for coal from the region will “remain under pressure by utilities’ continued move toward natural gas and renewable energy.”

Analyst Reactions

Close observers of the economics of the Powder River Basin have long expected some sort of consolidation in the region. What was surprising to most, however, were the names of the firms to actually go through with it.

“I think if anybody expected this sort of consolidation in the basin, it was going to be from one of the smaller players,” said Robert Godby, the director for the University of Wyoming’s Center on Energy Economics and Public Policy. “I don’t think many people were expecting the two strongest companies with the two largest mines to look at each other and, eventually, make that step.”

This trend, Godby said, is a sign of an overcapacity in the Powder River Basin. Where in traditional sectors businesses would simply close up shop, coal mines are costly to shut down, an unattractive fate for any publicly traded company with shareholder obligations to consider. Traditionally, coal companies could choose to be more aggressive, fighting to cut into the market share occupied by their competition, in order to boost their earnings. However, under the current conditions of the market and a structural decline for coal in general, such a battle would only drive down costs and further destabilize companies’ already slim profit lines.

As a result, companies are then forced to realign themselves in ways that either allow them to remain profitable or minimize their losses as much as possible. Under those conditions, coal industry insiders have seen the eventual consolidation between producers in the Powder River Basin as a foregone conclusion.

However, Godby noted both firms had in recent months scaled back their production due to oversupply in the market. To maintain their profitability, the two firms may have decided it would be easier to hedge their competition and maximize their profitability by joining together.

“They’ve created a marriage that forces them to cooperate, rather than compete, and that’s got to be better for both,” Godby said. “It’s one thing for smaller miners to compete for their market share, but if those two companies went toe to toe, trying to take each other’s market share, ... a lot of damage could be done to the market.”

Overall, Godby said the move is best interpreted as a movement for survival.

“I’m not convinced this action was taken to make coal-fired electricity more profitable,” he said. “The main concern here is maximizing the profitability of these miners’ operations.”

Mitigating Risk

Though Peabody said it did not anticipate any drawdowns in hourly mining positions at either facility, some industry experts speculated mining workers across the state could be adversely affected in other ways.

“Operational efficiencies,” for example, could mean the possibility for reductions in management or the elimination of redundant positions within both companies. Meanwhile, strong competition from the newly dominant joint venture could potentially claim a larger share of the market in the Powder River Basin, leading to job losses for other coal operators in the region.

“I’m sure a lot of communities are hoping that healthier coal companies mean more secure jobs,” Godby said. “But it’s also possible merged operations means some jobs are no longer necessary. I guess that remains to be seen.”

Others, like Clark Williams Derry, an analyst with the environmentally focused Sightline Institute, saw glimpses of a cautionary tale out of Appalachia and the closure of Patriot Coal — a Peabody spinoff of economically shaky mines in West Virginia. Williams Derry described Patriot as a company that was “set up to fail,” meant only to free Peabody out of the reclamation costs and retiree obligations for which those companies would have been accountable in a closure.

While merely theoretical, Williams Derry speculated that both companies could spin off their joint venture in a similar fashion five to seven years down the line to potentially save themselves from similar obligations, should the mines no longer be profitable.

Though the joint venture for both companies could signify short-term sustainability, the merger could also signify a harbinger of a future drawdown for both companies in the Powder River Basin.

“This is not a game of tic-tac-toe; this is a game of chess,” Williams Derry said. “You have to ask what move they’re setting up next.”

Deal Isn't Done Yet

It is unclear when the deal will be finalized, CEOs for both companies said Wednesday. The transaction will likely be subject to scrutiny under U.S. antitrust laws, which regulate free market competition between competing industries. However, the landscape of the energy industry has changed, Kellow argued, presenting a compelling case for regulators in determining whether the sale should move forward.

“The transaction will require clearance under the U.S. Antitrust Laws and certain jurisdictions outside of the United States,” Kellow said on the call. “However, we believe the case for customers is compelling. The landscape of U.S. energy production has changed while the nature of coal production has not. Coal is not just competing against coal — it’s competing against natural gas and renewables. The announcement of the joint venture occurs as thermal coal industry conditions have been challenged by increased competition in the face of inexpensive natural gas from shale production, growing build-out of subsidized renewable energy capacity, coal plant retirements, strict regulations and limited power demand growth.”

The assets involved in the deal include some of the nation’s largest producing mines which, combined, account for more than a quarter of the nation’s total coal production. The North Antelope Rochelle mine accounted for 98.4 million tons in sales volume in 2018, with Black Thunder producing 71.1 million tons. Those two, respectively, ranked first and second by a wide margin in U.S. coal production in 2017, with Caballo ranking 13th, Rawhide 15th and Coal Creek 17th, according to the most recent U.S. Energy Information Administration rankings available. North Antelope Rochelle and Black Thunder alone accounted for more than 22.2 percent of U.S. coal production that year.