No Solution At All

November 13, 2019 - Questions continue to arise about the cost and technical feasibility of moving to an emissions-free grid by 2050. Or, in the case of the Green New Dealers, making that jump even sooner.

At a recent hearing on the subject, House Energy & Commerce Committee Chairman Frank Pallone, Jr. (D-N.J.) said, "a solution that is unaffordable or technologically infeasible isn't really a solution at all." Those were wise words that need to be repeated loudly and frequently.

The energy analysts at Wood Mackenzie found that moving to an all renewables grid by 2030 would conservatively cost $4.5 trillion. It was the kind of number that you might imagine candidates backing away from, or at the very least contesting. What has happened instead is just the opposite.

Presidential candidates have engaged in a game of one-upmanship over whose climate plan is more aggressive, more radical and more costly. Senator Bernie Sanders has so far set the bar rather high; his plan comes in at a whopping $16.3 trillion.

While candidates backed by activists talk about an at-any-cost approach, the tone from energy experts and grid managers is far different. At the same hearing where Chairman Pallone issued his warning about false solutions, experts from the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO), which runs the grid across much of the Midwest and parts of Canada, talked of the need for caution and an eyes-wide open approach to the hurdles ahead.

MISO warned: “maintaining reliability at the 40% renewable level becomes significantly more complex. The implications are very real. Today, we face more frequent and less-predictable occurrences of tight operating conditions on the electric grid compared to just a few years ago, and the challenges continue to grow.”

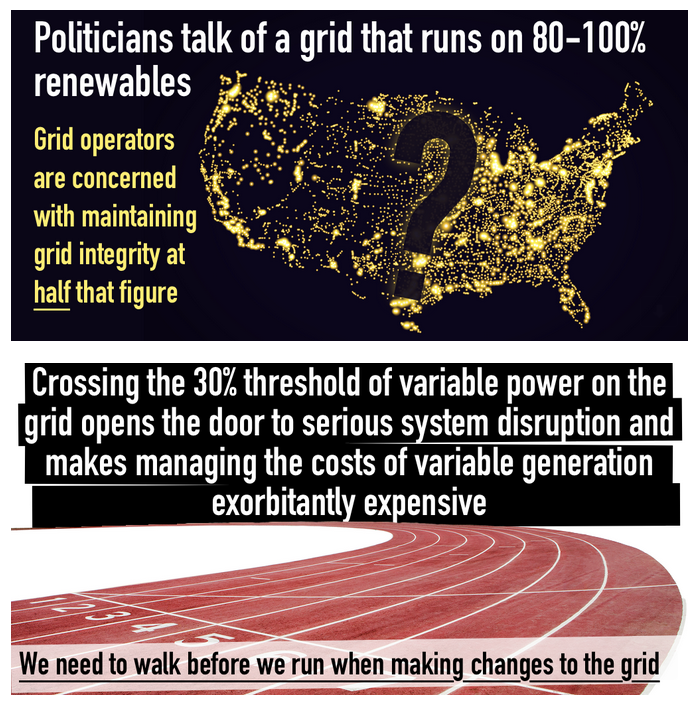

MISO’s warning highlights the significant challenges associated with greater reliance on intermittent sources of power. They’re concerned about the immense challenges of getting to 30 or 40% penetration of renewables. Going to 80 or 100%, as some candidates want, is at such a different level of complexity they haven’t even considered it. MISO is still trying to learn how to cost effectively – and reliably – walk before they can even think about running.

MISO’s experts pulled no punches. They testified, “we can no longer be confident that the system will be reliable for all 8,760 hours of the year based solely on utilities having enough generation capacity to serve load on the annual peak hour in the summer.” They continued, “we can no longer be confident that the traditional approach of marginal cost pricing will provide adequate financial incentives to prompt utilities and other types of entities to build the kinds of resources—with the right kinds of attributes—that the system needs to keep operating reliably going forward.”

These are alarming revelations that should steer our conversation about managing the path forward. But this on-the-ground realism is often getting overwhelmed by the cacophony of activist rhetoric. When raising questions about the practicality, affordability or technical feasibility of a proposed approach is slandered as obstructionism, you know you have a real problem on your hands.

The concerns MISO raises are hardly theirs alone. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) authored arguably the definitive study on integrating intermittent sources of energy onto the grid. NREL found that just crossing the 30% threshold of variable power on the grid not only opens the door to serious system disruption but the cost of managing the gulfs between the peaks and valleys of variable generation becomes exorbitantly expensive.

As for MISO’s concerns about the market and traditional marginal cost pricing not being up to the challenge of providing the right incentives to ensure a reliable supply of power, those are concerns echoed by other grid operators as well.

Earlier this year, ISO New England, the grid operator in the Northeast, examined whether wholesale electricity markets provide adequate financial incentives for resource owners to make investments that ensure fuel security and reliability.

Their central conclusion was that, “in many situations, the answer is no.”

MISO and ISO New England’s warnings come as ERCOT, the grid operator in Texas, barely kept its grid from collapsing this summer as peak electricity demand eclipsed supply on multiple occasions.

While activists are determined to race ahead, grid operators, utilities and energy experts are deeply concerned about managing the existing pace of change. The loss of fuel-secure, baseload power and the shift towards ever-greater reliance on variable sources of power is a challenge not to be taken lightly. It appears to already be pushing the limits of both affordability and feasibility—limits we must not breach. As concerns and warnings grow, we better do more than just listen.