New Exhibit Pays Tribute to Contributions of Women Miners

By Audrey Stanton-Smith

May 9, 2021 - Reporter’s Note: I had the pleasure of interviewing Zora Stroud 21 years ago, when she was recognized by the W.Va. House of Delegates for being the first woman to retire after 20 years of service in a West Virginia coal mine. Zora is now 83 and living with a son in North Carolina. Her quotes in this article are taken from my article that appeared in The Register-Herald on Feb. 23, 2000.

A few years ago, Diane Williams took her granddaughters to the Beckley Exhibition Coal Mine.

“I wanted to show my granddaughters what their great-grandmother did,” the Pennsylvania resident recalled. “So I took them through the exhibition mine, took them on that ride down into the earth to see what mining was like. And my granddaughters’ eyes were opened so wide. They could not believe my mother had done this.”

The great-grandmother they knew was much too tall to have worked in a tunnel with such a low roof. Their loved one liked watching old black-and-white cowboy shows on TV, not black dust gathering on her nice clothes. She enjoyed fishing, not shoveling. The great-grandmother they knew was too full of love and home cooking to have worked as hard as their tour guide explained coal miners did.

They didn’t know the groundbreaking woman in the coal-dust-covered overalls, the one wearing a utility belt as heavy as a child and a hard black hat that said “Big Black Mama.” They didn’t know the brave woman who stood tall against sexist and racial slurs while bent under a low, dark ceiling to support four children.

They do now, and so will other visitors to the Exhibition Coal Mine, where a new exhibit paying tribute to the contributions of Zora Stroud and other female miners will be ceremoniously unveiled this Mother’s Day at 2 p.m. (Though the Exhibition Coal Mine is not open on Sundays, the museum portion will be open from 1:30 to 2:30 p.m. today for the public unveiling. Stroud and her family plan to attend.)

Zora Stroud, pictured outside her home in 2000 when she became the first woman in West Virginia to retire after a 20-year career as a coal miner.

Photo: Rick Barbero

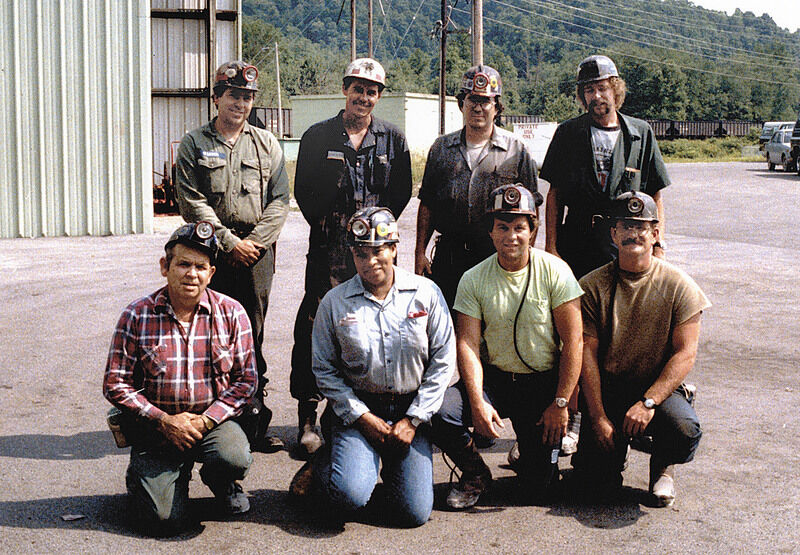

Zora Stroud, bottom row second from left, was the first female to retire from the mines in West Virginia.

During her days in the mines, Zora Stroud was known as "Chocolate Mama" by her fellow miners.

“I’m really glad we could do even such a small part, and I hate that it was overlooked originally,” said Exhibition Coal Mine Director of Operations Leslie Baker, who took the helm at the museum in 2014. Baker said the museum had hoped to unveil the new interpretive exhibit — designed by local graphic artist John Sellards to match the museum’s older pieces — last year, but was delayed by COVID.

“I want them to know what a wonderful and loving person my mother is,” said Williams, who expressed her concern about a lack of female representation in the museum to an attentive Baker during that visit with her granddaughters a few years ago.

“I want them to know how her strength and her faith kept her in that mine those 20 years,” Williams continued. “I want to give her the respect and show her the love that she showed so many people, and recognize the encouragement that she’s given to women all over the world, especially in West Virginia. I want people to look at the exhibit and know that once they put their mind to something, like my mother did, that they can do anything.”

It has always been Stroud’s children and their families — not Stroud, because she doesn’t seek attention for herself — who have shared their pride for their mother with others, Williams noted. It was a daughter-in-law, Eulanda Saunders, who stood by her in 2000, when then-W.Va. House Speaker Bob Kiss honored Stroud for being the first woman to retire after 20 years of service in a West Virginia coal mine. And it was Williams who inspired Baker to create the new exhibit.

“I don’t think my mother understands the impact that she’s made on the coal mining community for women or just for coal miners at all in the state of West Virginia,” Williams said. “To be a woman who had a great run of it for over 20 years, that’s important to our family, to our legacy.”

Stroud began her mining career in 1977, but it wasn’t her first job. A West Virginia native, she had worked in home health after high school during a stint in New York. But when aging and ailing parents needed her back home in Glen White, she didn’t hesitate to return to the Mountain State. It was soon apparent, though, that she couldn’t earn enough money as an LPN to support her three boys and her mother. (Diane, the oldest of Stroud’s four children, remained with family in New York.) And Stroud had grown weary of, as she described her nursing job, “cleaning hockey.”

One day, Stroud noticed a neighbor she described as “scrawny” walking home from the mine with his dinner bucket.

“He was a lazy boy,” Stroud said. “But I knew if he could do it, I could do it. I wanted a job in the mines. I would rather work than be on welfare.”

The timing was right. President Lyndon B. Johnson had signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, creating the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. In 1972, that act had been amended to establish affirmative action, requiring employers to hire minority workers. Coal companies began hiring women, and just a year after Stroud entered the mine, an advocacy group for women called the Coal Employment Project filed a lawsuit over sex discrimination in the hiring process. As a result, coal companies in Appalachia hired 830 women in 1978, according to the book “Daughters of the Mountain: Women Coal Miners in Central Appalachia,” by Suzanne E. Tallichet.

Stroud was no stranger to the profession. Like many in their Raleigh County home, Stroud’s father, James Edward Chambers, had gone into the mines at the age of 13, driving a mule train. Her uncle, Lewis Chambers, also worked in the mines.

“All my life that’s all I knew,” she said. “And I knew that’s where the money was.”

And for the next 20 years, seven days a week until the mine closed, she worked — hard. She began by earning $77 a day and good benefits, but by the time she retired, she was earning $117 a day, benefits, and a lot of respect.

Although no other women were working there when the mine closed in 1998, 10 of them worked at Maple Meadow when Stroud started. Most of them, in the red hats worn by rookie miners, were responsible for clearing the sump by dipping 5-gallon buckets into the mess and scooping it out.

“I went in as a red hat,” Stroud said, recalling her first days with a tough boss who wore a black one. “I told him that one of these days I’m gonna get my black hat and really show you something.”

She would show him and anyone else who crossed her path. Being a little “mean,” as she said in 2000, was what it took to earn respect in a male-dominated field where many of her co-workers seemed to relish in giving a black woman a hard time.

“Whatever they did to me one day, the next day I did it back to them,” she said. “I played their game.”

Miners who called her ugly names got called ugly names in return. Stroud carried one knife in her back pocket and another in the front of her belt, and she didn’t hesitate to pick up a steel bar to defend herself if she ever needed to do so. She said she never made much of it when miners told racial jokes. Rather, she just laughed and told them she collected such jokes. Word spread, and eventually the jokes stopped.

“If they picked on me, I picked right back,” she said.

In addition to stopping inappropriate jokes, Stroud proved she could do anything her male counterparts could do. She could drag trees bigger than she was. She could set roof bolts. She could hold her own on a picket line. And she could outwork her younger co-workers.

“Anything they said I couldn’t do made me try that much harder,” she said.

As her skills and personality became evident, her coworkers gave her a nickname, something she viewed as a sign of respect and painted on her now black hat.

“My mother’s work ethic spoke for itself,” Williams said. “She did her job, and they gave her the respect. That respect is why they called her ‘Big Mama’ or ‘Chocolate Mama’ or just ‘Mama.’ The way she worked made a difference, and they just grew as a family down there.”

Stroud found even more strength underground with help from above. Roughly 10 years before she retired, Stroud decided she didn’t want to “lose my kids to the world.” At the advice of a fellow miner, she began attending church.

“I received the Holy Ghost, and I stopped being mean,” she said. She even started leading prayers before going underground, and she marked the initials of Jesus Christ on rock dust bags, just so she’d have a reason to explain why.

Stroud’s last 15 years in the mine were spent on a belt job that sent timber up and down the line. She’d always have her belt straight, and she was frequently told to help the men get their belts the same way after she’d finished with her own. Maybe it was that kind of help that led one of her fellow miners to push her out of the way when something went wrong. That man broke his back to save her.

“It was hard, physically,” she said. “I thank God I was big and strong.”

Stroud said she is thankful she was healthy enough to continue working, uninjured, until the mine closed and she retired in 1998.

“I’m very grateful that I made my 20 years,” she said.

When she retired, Stroud delighted in the time she found to care for family and her Glen White community. She cooked for neighbors and often gave them rides to medical appointments. Just as importantly, she took pride in the successes of her children. And when a grandson’s social studies project focused on coal mining’s impact on his family, she called it a blessing.

“My mother always said it was the best thing she could have done, going into the coal mine,” Williams said. “It gave her the opportunity to earn a good wage and a pension. It gave her the opportunity to have a lifestyle that she wanted to have for her family. … She has a strong faith in God, and she believed every day she was down there that God had given her an opportunity to do that, to take care of her family.”

Her family now takes care of her. Stroud, 83, lives in Charlotte, N.C., with her son Nathan, who works for the Veterans Administration Hospital after serving in the U.S. Navy for 20 years. Another son, Christopher, followed his mother’s footsteps into the mines. He continues to work for Affinity Coal. A third son, Alfred, has passed away, but Williams said he, too, learned a strong work ethic from his mother. Williams, Stroud’s oldest child, retired recently as a senior manager after a 41-year career in information technology with Johnson and Johnson.

“I worked some very long and very challenging hours,” Williams explained. “I would sometimes be up all times of day and night, because the international businesses that we supported required a lot of attention. And my coworkers would say to me, ‘How do you always keep a smile on your face?’ And I would tell them, ‘It’s because no matter what trial I go through, I’m above ground. I’m looking out this window at a tree or a flower, and I imagine my mother, down 700 feet in the earth, in a coal mine. So what do I have to complain about?’ And then they understood. ...

“She imparted that coal miner work ethic and that sense of gratitude in all of us, as did my grandfather before her, and we are so thankful.”

Williams said her family is also thankful for the new exhibit.

“We are just very appreciative of having this honor,” Williams said. “We want to thank the Beckley Exhibition Coal Mine and Leslie Baker for sharing this legacy there for her children and grandchildren and their children and grandchildren, and for everyone, to receive.”

The Exhibition Coal Mine is open Tuesday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.