Utilities Face Greatest Threat as Climate Risks Intensify

September 20, 2021 - Climate change is pushing power, gas and water companies to the frontlines of an intensifying battle against natural disasters that is set to increasingly hit the profits of businesses around the world.

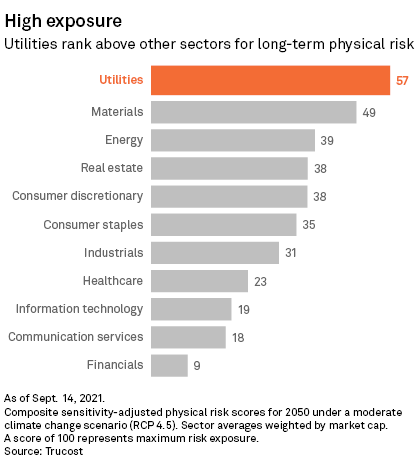

Utilities face the highest combined physical risk from climate hazards like water stress, storms and wildfires among different industries, according to an analysis of data from Trucost. The analysis, which ranks threats to the physical operations of around 15,000 public companies, shows utilities' vulnerability to physical climate risks generally tops other capital-intensive sectors like industrial manufacturing, oil and gas and real estate.

Extreme weather events are likely to become even more frequent and intense as a result of rising temperatures, and experts argue that many businesses are not fully prepared to cope with the physical and financial impacts.

"Physical climate risk really is everywhere," said Christopher Schwalm, risk program director and senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center, a U.S.-based think tank that works with companies on pinpointing their climate risk. "That hasn't quite achieved the level of resonance it ought to have in the broader corporate world."

Among the seven different physical risk factors assessed by Trucost, water stress ranks by far the highest for utilities. Aside from water utilities and hydropower producers that will see their primary resource stretched by increasing droughts, thermal power generators like coal and nuclear plants also rely on vast amounts of water to cool their systems.

On top of other destructive events like wildfires, hurricanes and floods, companies are also set to suffer more from heatwaves that shut down operations or create unworkable conditions for employees, for example workers installing and maintaining power lines.

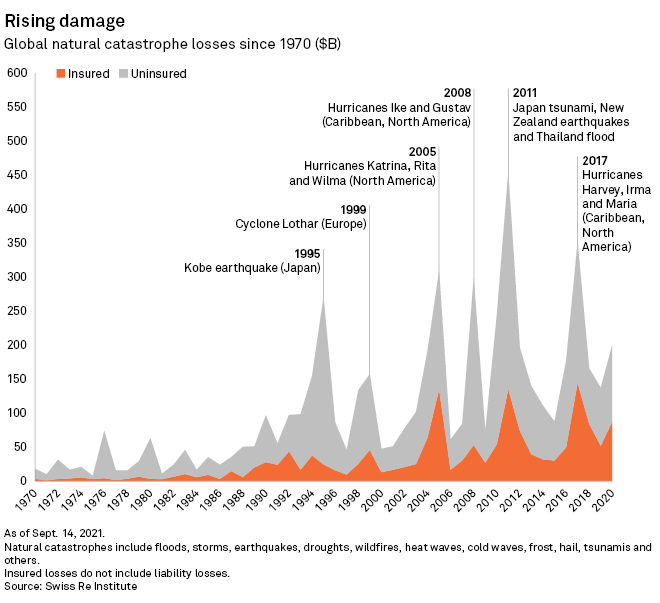

Recent decades have already seen a marked increase in damage wrought by extreme weather. The first half of 2021 brought winter storms, intense heatwaves and severe flooding that pushed global insured losses from natural catastrophes to an estimated $40 billion, the second-highest total on record, according to the Swiss Re Institute.

Utilities have felt the impact: Power producers in Texas lost more than $10 billion in profits when a winter storm froze gas and wind turbines in February, driving up wholesale power prices. In Germany, floods took out transmission lines, shut down power plants and damaged one of RWE AG's coal mines. And in Louisiana, hurricane Ida crippled Entergy Corp.'s power lines like no storm since Katrina.

High-profile events like these tend to move climate resiliency up the agenda even for unaffected companies, said Rich Sorkin, the CEO and co-founder of Jupiter Intelligence, which provides climate risk analytics. The company, which counts utilities in the U.S. and Europe among its customers, is already seeing a bump in business that can be traced back to the February freeze.

"Everyone is now starting to pay attention to this, if they weren't already," Sorkin said.

The coronavirus pandemic has similarly caused a broader awakening to the risk posed by extreme events with outsize impacts, said Tony Rooke, director of climate transition risk at Willis Towers Watson, a risk adviser and insurance broker.

'Business as usual'

Regulators are also starting to take note: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recently asked the country's top federal energy regulator to take a harder look at the climate resiliency of a natural gas pipeline project in Louisiana, particularly highlighting the risk of "climate change-induced storms and sea level rise" along the Gulf Coast. In Europe, companies are also increasingly required to factor climate change into their planning processes.

Meanwhile, utilities' investments to cope with more frequent disasters is already at or near record levels, said Paul Munday, director of climate adaptation and resilience at S&P Global Ratings. Companies are burying power lines, bulking up their insurance coverage and developing management plans for threats like wildfires and droughts, he said.

RWE, which suffered a combined €435 million loss from the Texas storm and German floods, declined to comment for this story. But CEO Markus Krebber told investors on an earnings call in August that the company would build back its damaged infrastructure more securely to withstand similar events in the future.

Entergy is in the middle of a nearly $7 billion program to upgrade its transmission lines after another hurricane already wiped out part of its network in 2020. And California's PG&E Corp., frequently invoked as the first high-profile climate casualty after its lines sparked devastating wildfires and pushed the company into bankruptcy, plans to spend up to $20 billion to bury its wires.

"We're seeing [investment in climate adaptation] increase across the utilities sector," Munday said, noting that European utilities tend to be better prepared than companies in the U.S., which often operate across larger areas. Utilities as a whole face a significant challenge in balancing massive investments to upgrade their infrastructure with high standards of availability, he said.

"They can't be everywhere all at the same time. So they have to make decisions in the context of uncertainty and where the biggest fires they are fighting are," Munday said.

Still, while experts say utilities have been more proactive than many other sectors, action is often limited to the largest companies and even those have blind spots. U.S. power companies alone face a $500 billion investment gap to properly future-proof their assets, according to ICF, a consultancy.

"A lot of it is still in business as usual," Rooke said, pointing out that many companies' plans still look at historical trends. "They're missing a trick. When it comes to climate, the world of the future is not dictated by what the past is."

'A fatal combination'

At the same time, climate-related risks also vary significantly across the world. Temperature rise will particularly cause operational challenges in regions like the Tropics, China's eastern seaboard, the Mediterranean, as well as northern regions exposed to melting permafrost, according to Schwalm, the Woodwell scientist. Complicating the picture are global supply chains, which expose many companies to climate risks even if their assets are not directly affected.

"You really need to think about this in a holistic way," Schwalm said.

And even though utilities are often able to recoup losses through customer rates, increasing catastrophes will put more strain on the system. Jupiter's Sorkin also sees an underappreciated risk for the industry in the fact that rate bases themselves will shift: The population and load in New Orleans are still below pre-Katrina levels, while Houston has seen substantial net migration because the city is seen as much more resilient.

"This stuff plays out in very unexpected ways," he said.

Companies who act fast to address climate threats will ultimately gain an edge over their peers and be better positioned to weather the kind of devastation wreaked on PG&E, the power producers in Texas or Tokyo Electric Power Co. Holdings Inc., the utility whose nuclear plant was damaged by the 2011 tsunami in Japan, Sorkin said.

"Slow [action] and bad luck is a fatal combination for boards and executives," he said. "These are all climate-related disasters that should have been planned for."