New Role for Ol' King Coal

By Dennis Webb

May 2, 2016 - A new report in Colorado's North Fork Valley coal industry is providing some hope, if not for the future of mining then at least for putting a mining byproduct to use.

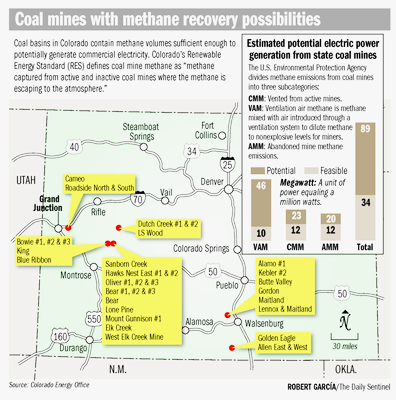

A report prepared by a Grand Junction company for the Colorado Energy Office finds a possible new role for Ol’ King Coal. It highlights the potential to develop 89 megawatts of electricity from methane vented from active and abandoned coal mines in the state, with 34 megawatts being economically and technically feasible to produce. Moreover, it finds that most of both the potential and feasible amounts involve mines in the North Fork Valley.

“Clearly, efforts to promote coal mine methane-to-energy projects in this (North Fork) region would be considered the greatest opportunity in the state,” says the report, prepared by Ruby Canyon Engineering.

In addition, it identifies areas near Redstone, in the Cameo area, and in Walsenburg and Trinidad as having high potential for electricity generation from methane from abandoned mines.

“I was thrilled to see that report. It’s about time somebody starts advocating for this process,” said Evan Vessels, assistant administrator of Denver-based Vessels Coal Gas Inc.

His company, led by Tom Vessels, already has been involved in putting together one project to generate electricity from mine methane, at Oxbow Mining’s now-closed Elk Creek Mine site in Somerset. The 3-megawatt project started producing in 2012, just before the mine began experiencing problems that stranded its longwall mining equipment, leading to its shutdown. Despite the end of mining, methane continues to come from the site, and Oxbow Mining president Mike Ludlow thinks it will do so at levels likely to continue powering the plant for another seven to 10 years.

“It’s been running very well. It’s been running very consistently for the past two years even though the mine has been shut down. … We’re very pleased with the performance and how the facility is actually performing,” Ludlow said.

The electricity goes into Delta-Montrose Electric Association’s power grid, but Holy Cross Energy, based in Glenwood Springs, ultimately pays for the power under what’s called a “wheeling” arrangement.

“It’s been a very reliable baseload facility for us. It’s very small but it’s been operating very well and keeps kicking out the electricity to us,” said Diana Golis, senior manager of power supply and contracts for Holy Cross.

DMEA has been monitoring the project with interest because of the potential the utility knows exists when it comes to possibly tapping into waste methane from the North Fork’s mines. Jim Heneghan, renewable energy engineer with the Delta-Montrose Electric Association, said electricity generated from methane could provide consistent baseload power, or could provide a dispatchable, on-demand power supply capable of helping meet needs during peak or intermediate usage periods.

And then there is the environmental upside of reducing methane emissions. Venting methane into the atmosphere rather than burning it has significant greenhouse gas impacts. Short-term, methane is a far more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

Heneghan said DMEA’s membership and board have supported the idea of tapping coal mine methane as energy.

“To have an environmental benefit in conjunction with a potentially versatile resource (in terms of meeting varying electricity demand) is really quite appealing,” he said.

Said Susan Carollo, spokeswoman for the Colorado Energy Office, “It is a local resource, and when it is harnessed it can benefit the local community.”

New Law Spurs Study

The Colorado Energy Office had the study done because it is charged with promoting the state’s renewable energy standard, passed by voters in 2004 and imposing minimum requirements on utilities for use of renewable sources. In 2013, the state Legislature decided to add coal mine methane as an eligible resource for meeting those requirements.

Christopher Worley, director of policy and research for the office, said that while the cost of wind and solar farms has fallen since 2004 to the point that they can compete with coal and natural gas as electricity generation sources, eight other technologies, from coal mine methane to small hydropower to geothermal, also qualify under the standard.

“The Colorado Energy Office is interested in identifying market potential and market barriers for those eight technologies so that all of Colorado’s energy resource can be utilized,” he said.

It paid $15,000 for the coal methane study.

“Ruby Canyon Engineering is an excellent local Western Slope resource with years of experience with coal mine methane recovery projects. Their familiarity with Colorado’s mines and technical experience with (greenhouse gas) accounting made them a natural partner on this project,” Worley said.

According to the report, as coal forms in geological formations, methane becomes trapped within coal seams and surrounding strata. Methane accumulation increases with depth, meaning that the opportunities for recovering and using economical quantities of the gas are generally limited to underground rather than surface mines.

The report says that nationwide in 2013, U.S. coal “liberated about 134 billion cubic feet (bcf) of methane from coal mining, enough to heat almost 2 million households for one year.”

It says Colorado mines reported about 7 million bcf of emissions in 2013.

Much of the vented methane consists of what’s called ventilation air methane, which is methane diluted to a percent or two in active mines to help protect workers from explosions. That makes it hard to use, something accounted for in the study’s estimates of potential versus feasible methane use.

For just three North Fork mines — Elk Creek, Arch Coal’s currently operating West Elk Mine, and Bowie Resource Partners’ recently idled Bowie No. 2 Mine — it estimates the potential for total electricity generation at 69 megawatts, enough to power some 72,500 households a year. But 46 of those megawatts are attributed to ventilation air methane.

The report estimates that it’s more realistic to think that 26 total megawatts could be generated from mines in the Somerset area. This includes abandoned mines in that area.

To improve economic viability, the report suggests potential for individual projects tapping into multiple mines in certain locations, such as Somerset, outside Redstone, and in Mesa County. The Cameo and nearby Roadside North and South mine sites hold potential for such development in Mesa County, it says. The Redstone area was renowned for gassy mines that experienced some deadly explosions. This month marked the 35th anniversary of a blast that killed 15 miners at the Mid-Continent Resources mine.

A Call to Action

Ted Zukoski, an attorney with the conservation group Earthjustice, welcomed the release of the new study, citing the climate impacts of coal methane emissions.

“This report shows there are practical technologies coal mines can use to cut that pollution, and new incentives to turn that pollution into energy and money,” he said. “It’s a welcome antidote to the ‘can’t do’ attitude of some mines. Arch Coal’s West Elk mine, for example, has for years refused to capture or combust methane because it doesn’t think it can turn a profit from its pollution.”

An Arch Coal spokesperson couldn’t be reached for comment on the new report.

Zukoski said methane capture should be not just encouraged but required, and that it doesn’t make sense not to regulate emissions from mines when such regulation is now occurring in the case of oil and gas development.

In 2014, the Bureau of Land Management, which handles federal coal leasing, said it was seeking comment on a possible rulemaking to reduce methane waste from mining, by allowing the methane’s capture, use, sale, or destruction through flaring. The undertaking is part of President Obama’s strategy to cut methane emissions as part of his climate action plan.

Colorado BLM spokesman Steven Hall said this week the agency “is currently developing guidance that would enable coal lessees to capture and sell waste mine methane. We do not have a timetable for completion of that guidance.”

He said he couldn’t speculate whether methane capture would be voluntary or mandatory under the rules. The BLM also is grappling with the issue of how ownership of gas rights applies if a mine wants to use or sell methane.

In Oxbow Mining’s case, that issue was resolved by the fact that the oil and gas rights for the acreage involved are owned by Gunnison Energy Co. Both companies are owned by industrialist Bill Koch.

Other challenges loom. Ludlow believes there’s potential to add 5 or 6 megawatts of power generation at the Elk Creek Mine site, but he said it can be hard for small-scale plants to compete on an economy-of-scale basis with larger ones.

Heneghan agreed that scale matters, but said that something such as a 5-megawatt project would be large enough to be of interest to DMEA.

The existing project marked the teaming up of an unusual cast of players. The Aspen Skiing Co. picked up $5.5 million of the $6 million cost as a green initiative designed to produce the equivalent of enough power for 2,000 homes or all of its operations, including four mountains, three hotels and 17 restaurants.

Evan Vessels said Holy Cross can claim renewable energy credits for the project and also sell carbon credits through a California program, as can Vessels for excess methane it flares at the plant rather than it being released to the atmosphere.

Said Vessels, “I think that’s really where the money is going to be, in destroying methane (through combustion for power generation or flaring) to earn carbon offsets that you can sell to emitters.”

The new report recommends further developing carbon offset protocols and other financial and tax incentives to encourage coal methane capture and use.

Said Worley, “The Colorado Energy Office will continue to work with project developers and our state’s utilities to expand coal mine methane generation in the future.”

The waste-methane pumping station at the Oxbow Elk Creek Mine in Somerset is all that’s left in terms of energy extraction at the now-abandoned coal mine

A new report says the potential for methane capture and power generation is an untapped one and could be utilized at underground coal mines across the region