A Crusader in the Coal Mine, Taking On President Obama

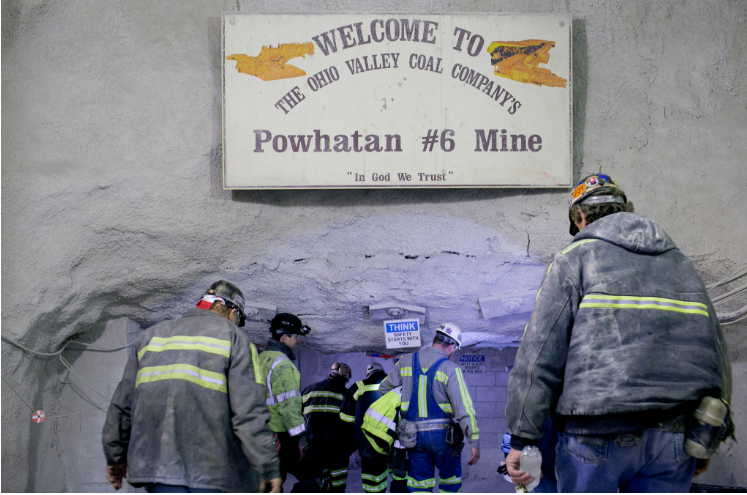

May 2, 2016 - The rolling hills of eastern Ohio show few signs of the frenzied activity unfolding hundreds of feet underground. Inside the Powhatan No. 6 mine, a machine the size of a city bus is slowly slicing the earth, scraping out coal and sending it on a 40-minute ride to the surface.

“It will see the light of day for the first time in 200 million years,” says Robert E. Murray, the 76-year-old chairman of the Murray Energy Corporation, rolling toward the coalface, where the coal is cut out of the rock, in an electric cart.

The digging occurs at the distant end of a forbidding maze of tunnels stretching more than 16 miles into the earth. The walls are coated with “rock dust,” or pulverized limestone, which acts as a fire retardant and gives the place a chalky, ethereal appearance. It is mostly silent but for the occasional whoosh of air venting from above.

This is a special place for Mr. Murray, who likes to tell the story of how he sold his children’s toys and mortgaged his home to acquire this mine — his first — nearly 30 years ago. He went on to build the nation’s largest independent coal producer by pioneering efficient new technologies like longwall mining, where the cavern ultimately collapses in on itself after yielding considerably more coal than traditional underground mining methods.

Mr. Murray is also the architect of the most serious challenge to the Obama administration’s environmental goals, particularly its policy on climate change. He has filed more than a half dozen lawsuits against the administration, including several challenging its landmark policy to curb greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired power plants. In February, he scored a big victory when the Supreme Court temporarily blocked the administration’s plan until an appeals court can consider an expedited challenge this summer.

The expansion of its mining business at a time of deep industry disillusionment, coupled with an activist agenda, has made Murray Energy one of the leading forces combating environmental regulations. And it has made Mr. Murray a galvanizing champion of a once dominant industry fallen on hard times.

For him, any attempt to regulate pollution from power plants is a plot not only to destroy coal producers in the United States but also to take control of the nation’s electrical supply. He blames regulators in Washington intent on accumulating power and handpicking winners and losers. “What it is is a political power grab of America’s power grid to change our country in a diabolical, if not evil, way,” he says. “Thank you, Obama!”

As the nation struggles to come to terms with greenhouse gas emissions, climate change and mining’s environmental toll, Mr. Murray stands at the center of the economic, social and political debate. His life goal is to see that coal production in America remains vibrant — even as his critics say he is waging a doomed, rear-guard battle against inevitability.

Electricity from fossil fuels, including coal, remains the single biggest contributor to global carbon emissions, which scientists blame for rising temperatures.

The business faces challenges from not only toughening environmental standards but also cheap natural gas resulting from the practice of hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking” — breaking up the bedrock to extract more oil and gas. This year, for the first time, natural gas is expected to pass coal as the main source of fuel for power plants.

A Life in the Mines

If Mr. Murray helped remake the modern American coal industry, then coal made the man. He started mining at age 16, a few years after a mining accident left his father paralyzed. His own neck has been broken three times. Over the years, his technological expertise has helped keep mines working that might otherwise have been shuttered long ago.

And he says he vehemently believes that humans are not responsible for global warming. Last year, he said Pope Francis was “totally wrong” for calling climate change an urgent issue.

On this day, Mr. Murray descended into the Powhatan No. 6 mine for what would probably be his last visit. The mine will close in November when it comes to the end of its productive life after nearly a half-century in operation. Most of the 431 miners are likely to be laid off.

“This is a human issue for me,” Mr. Murray says. “It kills me. Lives are being destroyed deliberately by some and by the ignorance of most.”

Moving deeper into the mine, he passes a pair of men drilling into the ceiling. “We appreciate your work,” he tells them.

Despite the obstacles, Mr. Murray is doubling down. In 2013, his company acquired the coal business of Consol Energy for $3 billion, nearly doubling its mines with the addition of five more. Last year, it bought a stake in Foresight Energy in a $1.37 billion transaction. Murray Energy now has the capacity to produce about 10 percent of the nation’s coal.

“The coal industry is being destroyed,” he says. “And it’s scary to me because electricity is a staple of life — like potatoes were to the Irish. And Obama has largely destroyed reliable, low-cost, affordable electricity in America.”

The day was taking its toll on Mr. Murray, who had been up since 5 a.m. and had flown by helicopter to a meeting in Akron with one of his biggest customers, the FirstEnergy Corporation. That meeting, which lasted six and a half hours, had not gone well. The sides could not agree on a new price for coal, with the power utility demanding more concessions from its supplier.

The walls of Murray Energy’s corporate offices are lined with mementos and pictures, and his own office is decked with small military plane models. Nearby stands a recent Christmas gift from a customer: a life-size statue of Mr. Murray, wearing a Scottish kilt in the Clan Murray tartan.

Coal mining runs in the family. Mr. Murray is a fourth-generation miner, and his three sons all work for the company. His father was paralyzed from the neck down after falling in a stairway in 1948, when Mr. Murray was 9 years old.

Those were tough days, he says, chicken dinner once a week. “We never bought fish,” he says. “Too expensive.”

He spent 16 years working underground, earning a degree in mining engineering along the way, and rising through the ranks of the North American Coal Corporation. He helped develop new mines in Ohio and North Dakota, among other places, and broke his neck in mining accidents in 1963 and 1969 (and in a car accident in 1987). By 1983, had become the company’s chief executive.

He was fired in 1987 over a disagreement with the board on dissolving and reincorporating the company in Delaware. Mr. Murray says the move was designed to shed employee benefits, and he refused to go along.

Within a year, with the backing of a local utility, the Cleveland Electric Illuminating Company, now called the FirstEnergy Corporation, he secured financing to buy the Powhatan No. 6 mine. He knew it was not being used to its full potential. And he had some ideas for fixing that.

One of the biggest expenses in mining, aside from getting the coal out of the ground, is transportation. Here, Mr. Murray took a novel approach.

On a map, he drew circles around power plants located near rivers — cheap transportation — then went shopping for mines nearby. Despite new environmental regulations on the horizon, he knew that even low-quality, high-sulfur coal could still be mined, provided that plants were equipped with scrubbers. He snapped up mines for a song.

Then, his masterstroke: longwall mining, which he helped perfect.

In traditional mining, individual “rooms” are cut into a coal seam and then supported by pillars to prevent a collapse. The result is that a lot of coal is left behind in the walls between the various rooms.

Longwall mining, on the other hand, extracts almost every last bit of coal.

It works like this: First, miners cut two parallel tunnels, often miles long, along either edge of the coal seam. After that, the longwall machine — a $350 million articulated piece of equipment equipped with a giant power drill — simply moves back and forth between the two tunnels, cutting off the coal face in three-foot slivers, like a giant salami slicer.

As the machine completes a pass, the excavated parts of the mine collapse. It’s more efficient and, Mr. Murray argues, safer.

The longwall machine can produce about 25,000 tons daily, a significant improvement on traditional underground methods, which typically produce up to 2,000 tons of coal a day in a section. Today, Murray operates 17 of the 40 longwall mines in the nation.

“He’s been pretty darn successful at it,” says Bob Hodge, a coal expert at IHS Energy, a consulting firm. “And he answers only to Bob Murray.”

Black-Rock Blues

The fact is, coal’s century-long dominance is ending. As recently as 2008, it accounted for more than 50 percent of electric power. But last year, that slipped to about 33 percent. And natural gas is expected to overtake coal as the single largest fuel for electricity production for the first time this year, according to the Energy Information Administration.

One reason is fracking, which has pushed down gas prices. The other major coal killer is the adoption by the Obama administration of more stringent standards to regulate carbon emissions and other pollutants that contribute to climate change or are harmful to human health.

These regulations have prompted utilities in recent years to shut more than 400 coal-fired plants that could not comply with the new rules or would be too costly to upgrade with pollution controls. Coal plants retired last year equaled the entire coal capacity of Britain, according to the Sierra Club.

The impact on mining has been swift. Coal production in the United States peaked in 2008 at 1.17 billion tons. It has since fallen 24 percent to its lowest level in 30 years.

A November study by the consulting firm McKinsey & Company refers to the coal business as a “slow-motion train wreck” and estimates that the industry is about $45 billion short to cover all its debts and liabilities. Those would include pensions and employee-retirement benefits, as well as the cleanup cost of shuttered mines.

More than 40 producers have filed for bankruptcy protection in recent years, including some of the biggest. “The situation for coal in the United States is about as bad as it has ever been in modern history, and maybe even beyond that,” says Mark Levin, an analyst with BB&T Capital Markets. “I don’t think we’re done.”

This is taking a toll on mine workers, whose numbers have shrunk by 19 percent in the last three years, to about 75,000. A typical miner earns $83,700 a year, according to the National Mining Association. For a laid-off worker with only a high school diploma, if that, that kind of pay is nearly impossible to find.

“We’re getting shelled,” says Ryan Murray, the youngest of Mr. Murray’s three sons and the company’s director of operations. “We have to fight back out of necessity.”

One, known as the Stream Protection Rule, was proposed to limit surface mining near waterways. Mr. Murray argues that it would effectively condemn longwall operations as well by prohibiting underground mining under vast tracts of land. The company filed 14,000 pages of comments opposing the rule, which is still under consideration.

Another is the Mercury and Air Toxics Standards, which set limits on air pollutants like mercury, arsenic and metals. Murray Energy sued the Environmental Protection Agency and won a major victory last year after the Supreme Court struck down the rule.

But the celebration was short-lived for coal producers. While the case was wending through the courts, utilities did not wait for a legal resolution. Those most affected shut plants that wouldn’t meet the regulations.

A bigger battle still is taking place over the Clean Power Plan, a cornerstone of the Obama administration’s international commitment to cut carbon emissions. The plan would, by the year 2030, reduce carbon emission from power plants by 32 percent from 2005 levels. It was a major part of the administration’s pledge to reduce carbon emissions made at the international Paris Climate Conference, in December.

The power plant rule leaves it up to each state to find ways to reduce emissions by shifting away from coal to cleaner energy sources, including renewable energy and natural gas. Murray filed an early challenge to the draft rules, and 29 mostly Republican-led states and other coal producers eventually joined.

Their challenge argues that the E.P.A. does not have the power under the Clean Air Act to regulate carbon emissions and that the rules violate state sovereignty and state power to regulate local utilities.

In February, the Supreme Court temporarily blocked the administration’s initiative, dealing an early blow to the policy, though it did not rule on the merits of the case. Also, the ruling was issued by a court divided along ideological lines.

The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit is expected to hear oral arguments on the legality of the regulation in June. Ultimately, both sides are expected to appeal to the Supreme Court if they lose. This time, the parties could face a court evenly split between its left-leaning and right-leaning factions since the death of the conservative justice Antonin Scalia.

Fighting Words

The day after his coal-mine visit, Mr. Murray delivered a lecture at West Liberty University, a small public college in nearby West Virginia. There, about 150 students packed a hall to earn extra credit for their business class.

Mr. Murray came with a five-page speech titled “The Ongoing Destruction of a Major American Industry,” which, among other things, described the “regal, outlaw Obama administration.” But once he reached the lectern, the speech was forgotten. Instead, Mr. Murray spoke extemporaneously.

He warned the students about government bureaucrats (“They are rejects compared with people in the private sector”); about Bernie Sanders (“The problem with socialists is that they eventually run out of other people’s money,” paraphrasing Margaret Thatcher); about the leading Republican presidential candidate (“I’m not sure about Donald Trump”); and about Ivy League schools (“These schools are lousy”).

He announced that he was organizing a fund-raiser for Ted Cruz, though he pointed out that he was not endorsing him.

And finally, he shared his views on what he described as the Obama administration’s lies about global warming. It doesn’t concern Mr. Murray that his climate views run counter to the scientific consensus, which has found that warming is “unequivocal,” according to the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

“This global warming hoax,” Mr. Murray told the students, “it’s a movement that is destroying America.”

.png)

Robert Murray in April in the Powhatan No. 6 mine

The Powhatan No. 6 mine in St. Clairsville, Ohio, is nearly depleted after decades in operation