19th Century Coal Miners in Great Britain

September 2, 2017 - We are taking a closer look at coal miners, specifically in the 19th century. An initial search for miners reveals explosions, accidents, and strikes in the vast amount of mines operating across Great Britain. We will look at these topics in closer detail.

The first coal mine was sunk in Scotland, under the Firth of Forth in 1575. As the centuries continued, the population’s dependence on coal increased and more mines were opened, but it was during the industrial revolution that coal mining burgeoned. Coal was used to power the massive steam engines as well as to create iron. It would take 2 tons of coal to make 1 ton of iron. Mining villages opened in Lancashire, Yorkshire, South Wales, Northumberland and Durham. Whole populations of towns were dependant on employment from the mines.

Strikes

Many of our readers will remember the miners’ strike of 1980s. Strikes have been used by miners as a form of protest for centuries. To strengthen their cause, miners’ began to form unions in the mid-19th century.

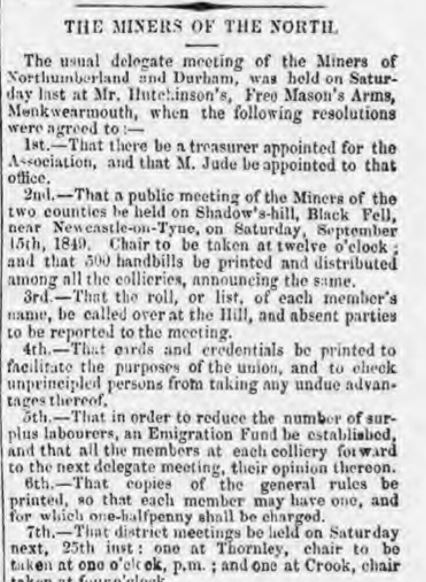

Northern Star and Leeds General Advertiser | August 25, 1849

The Northern Star and Leeds General Advertiser printed the minutes from a delegation of Miners of Northumberland and Durham. The minutes show that the delegation assisted miners on a number of levels. They created an Emigration Fund to reduce the number of excess labourers and they provided assistance to West Moor Miners who were on strike to resist a reduction in their wages.

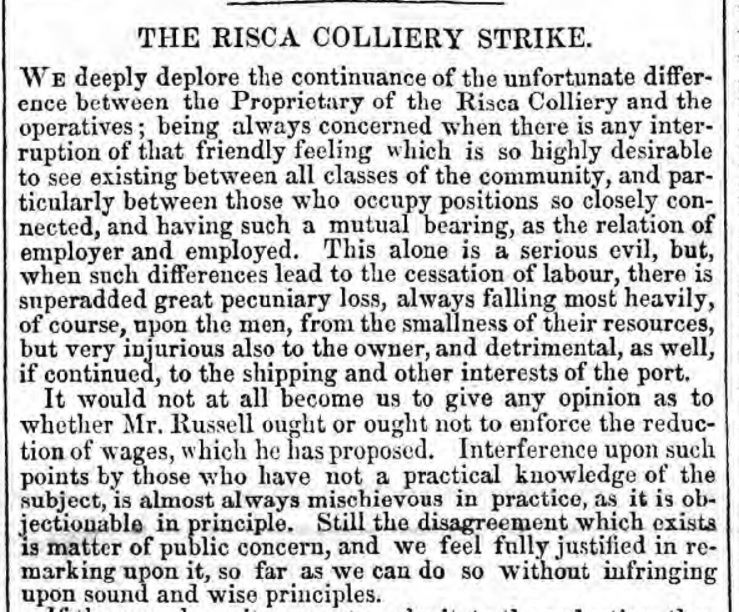

The working conditions of the mines and the long hours were difficult enough to endure without wages being reduced. We found numerous cases of miners’ strikes due to a reduction in wages. For example, the Risca Colliery Strike of 1849. The miners had ceased work in protest of a reduction in their wages. Only three years earlier, an explosion at Risca had killed thirty-five employees. The newspapers had mixed opinions about the strike. The Monmouthshire Merlin reviewed the effects of the strike on not just the workers, but those around them. ‘When such differences lead to the cessation of labour, there is superadded great pecuniary loss, always falling most heavily, of course, upon the men, from the smallness of their resources but very injurious also to the owner, and detrimental, as well, if continued, to the shipping and other interests of the port’. Another individual wrote to the same paper, taking the side of the colliery owner.

Monmouthshire Merlin | September 15, 1849

Monmouthshire Merlin | September 8, 1849

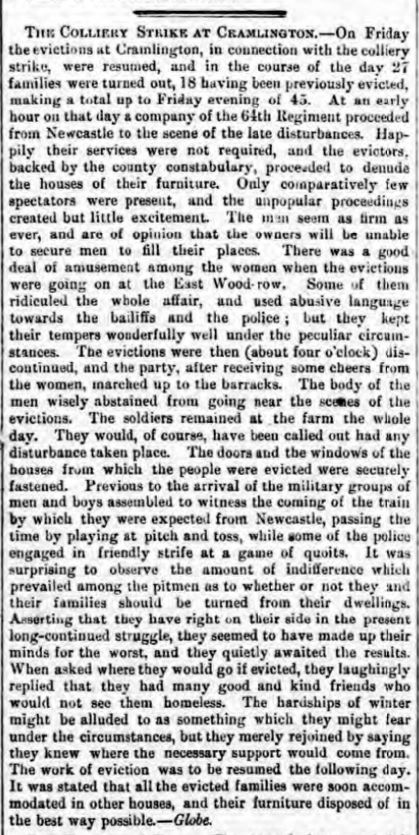

Dublin Evening Mail | October 24, 1865

In some factory towns, colliery strikes lead to evictions of families because the mine owners also owned the workers’ homes. Such as in Cramlington in 1865. A reporter for the Dublin Evening Mail was amazed that even in the face of eviction the workers still held their convictions. ‘It was surprising to observe the amount of indifference which prevailed among the pitmen as to whether or not they and their families could be turned from their dwellings. Asserting that they have right on their side in the present long-continued struggle, they seemed to have made up their minds for the worst, and they quietly awaiting the results.’

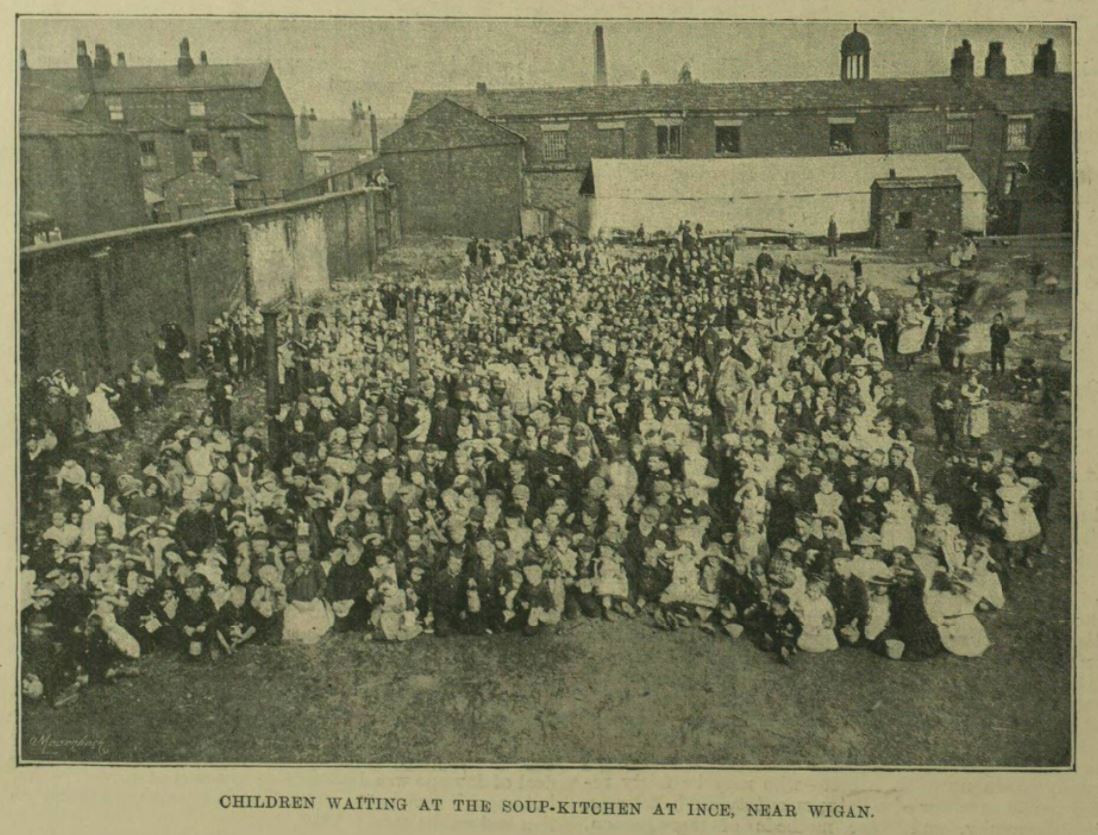

As demonstrated in this image, families were brought to near starvation during these strikes. This image from the Illustrated London News shows children waiting at a soup kitchen at Ince during the ninth week of a colliery strike in Lancashire.

Ilustrated London News Miners' Children Outside Soup Kitchen 1893

Working Conditions

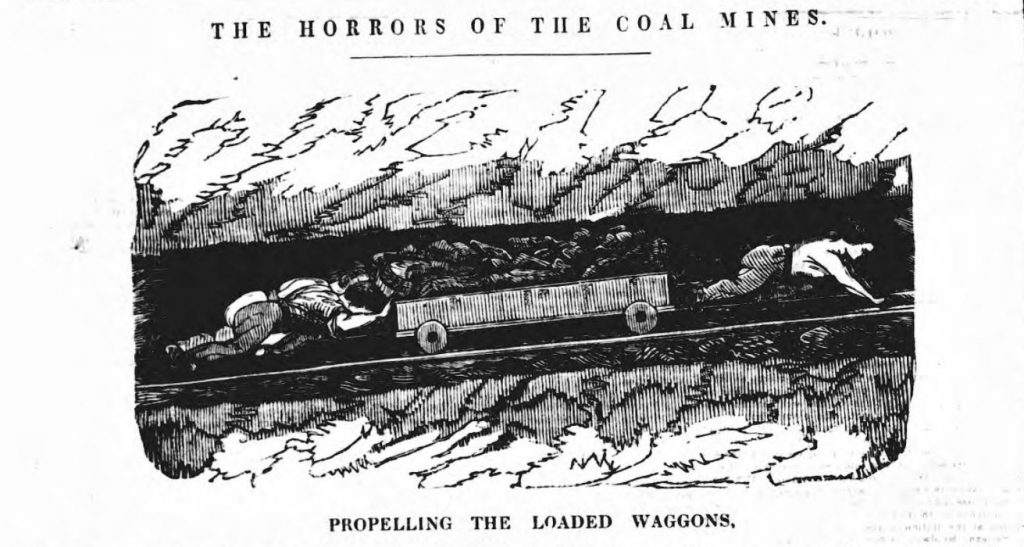

Along with the fighting for their wages, miners endured harsh working conditions every day. In the early 19th century, women and children also worked in the coal pits along with the men. Children as young 8 could be found working for 12 or more hours a day in complete darkness. Children worked as trappers. They opened and closed trap doors in the pits to allow for air ventilation. Women and older children were used to move the tubs or wagons of coal out of the mines. They were known as hurries and thrusters. The horrors of these working conditions came to light in 1842 with the Children’s Employment Commission. The commission interviewed children, women, and men who worked in the mines.

Children explained how they were fitted with a girdle and chain around their body to pull the coal out of the mine.

‘When I put on the girdle the blisters would break and the girdle would stick, and next day they would fill again! When I drew by the girdle and chain the skin was broken, and the blood ran down. I durst now say anything. If we said anything, they, the butty, and the reeve who works under him, would take a sticks and beat us!’

Childrens Employment Commision 1842

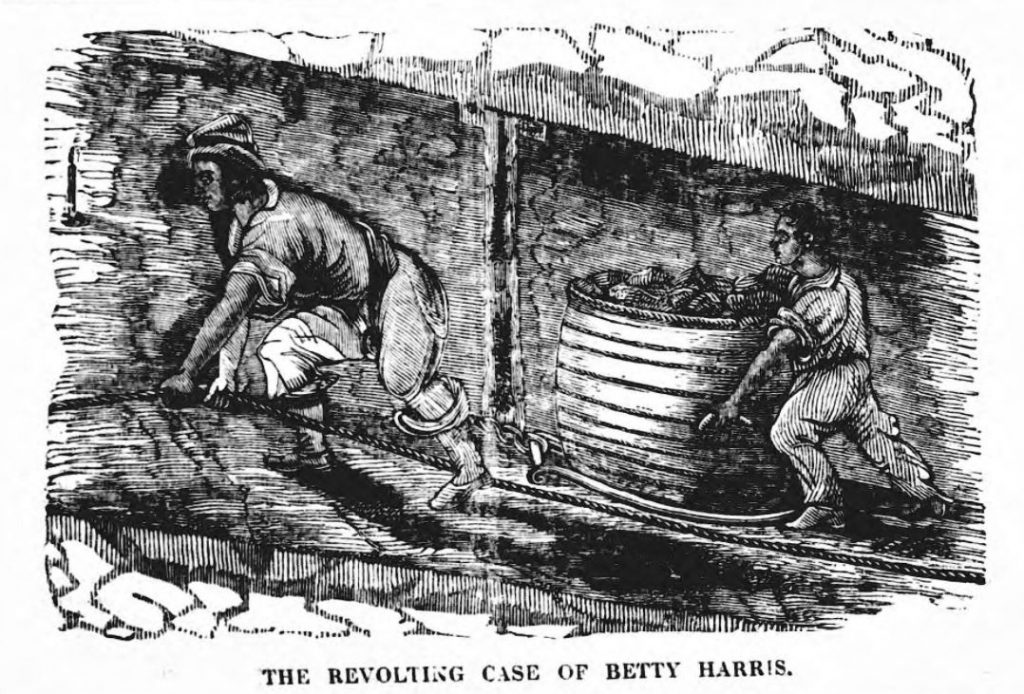

The commission found that it was not just the conditions themselves that were brutal but also the treatment of the employees by the owners. They found reports of beatings for those who were not quick enough or complained. Women worked in trousers alongside men who often worked with little to no clothes on because of the heat within the pits. Thirty-seven-year-old Betty Harris’ distressing testimony described pulling coal out of the pit on her hands and knees.

‘I have drawn till I have had the skin off me: the belt and chain is worse when we are in the family way. My feller (husband) has beaten me many a time for not being ready. I were not used to it at first, and he had little patience. I have known many a man beat his drawer. I have known men take liberty with the drawers.’

Children's Employment Commission

After the report, the public was horrified and Parliament passed an act in 1842 which prohibited women and male children under the age of 10 from working below the surface at the collieries.

Safety

Safety has always been an issue for mining from its early days to more recent mining accidents and catastrophes. In the 19th century, one of the biggest advances to mining safety was the invention of the safety lamp by Sir Humphry Davy, subsequently, it became known as the ‘Davy lamp’. The lamp helped to prevent explosions caused by the presence of methane in the pits. Methane was also known as ‘firedamp’ and ‘minedamp’. The holes in the screen around the flame did not allow the fire to ignite the firedamp or methane around the lamp. The flames of the lamp helped to notify miners of the invisible presence of flammable gases by burning brighter and with a blue tinge when flammable gases were present. The Durham County Advertiser printed a short description of Davy’s invention.

Davy's Safety Lamp

Miner Imprisoned 1879

Regulations were put in place that required all miners to use the new safety lamps. If they did not, and risks the safety of everyone in the colliery, they could be fined or imprisoned. A miner could also be disciplined for failing to operate his lamp safely. This report from Dundee Courier found that a miner was charged in contravention of the Moines regulation Act when he recklessly unlocked his safety lamp while working in the mine. He was sentenced to three months in prison.

Explosions

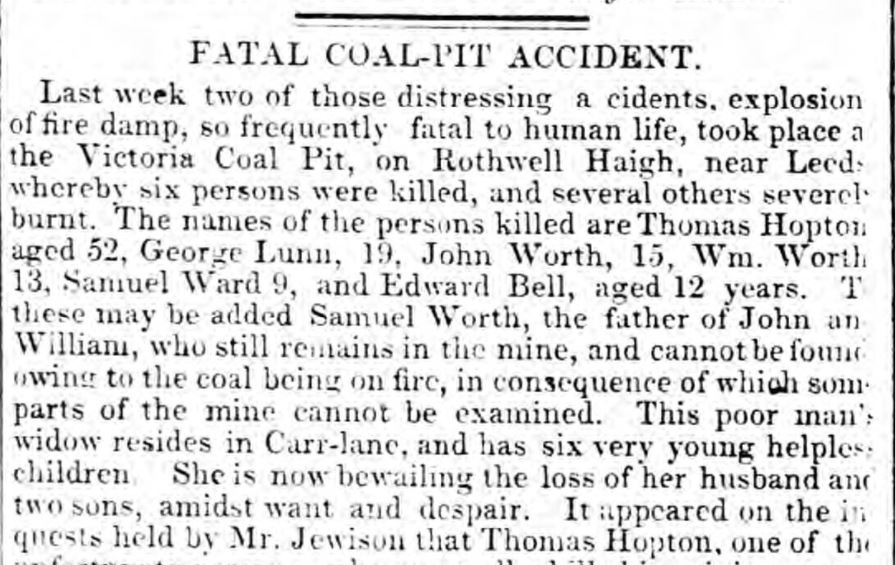

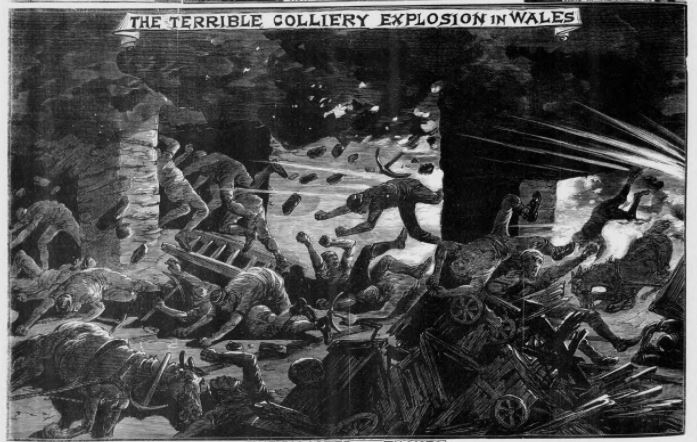

The introduction of the safety lamp was not enough to completely prevent explosions and accidents within the mines. The newspapers give us regular reports of explosions and accidents resulting in deaths such as these examples.

A fatal pit accident at Victoria Coal Pit on Rothwell Haigh near Leeds. Six persons killed, one as young at 9.

Fatal Coal Pit Accident

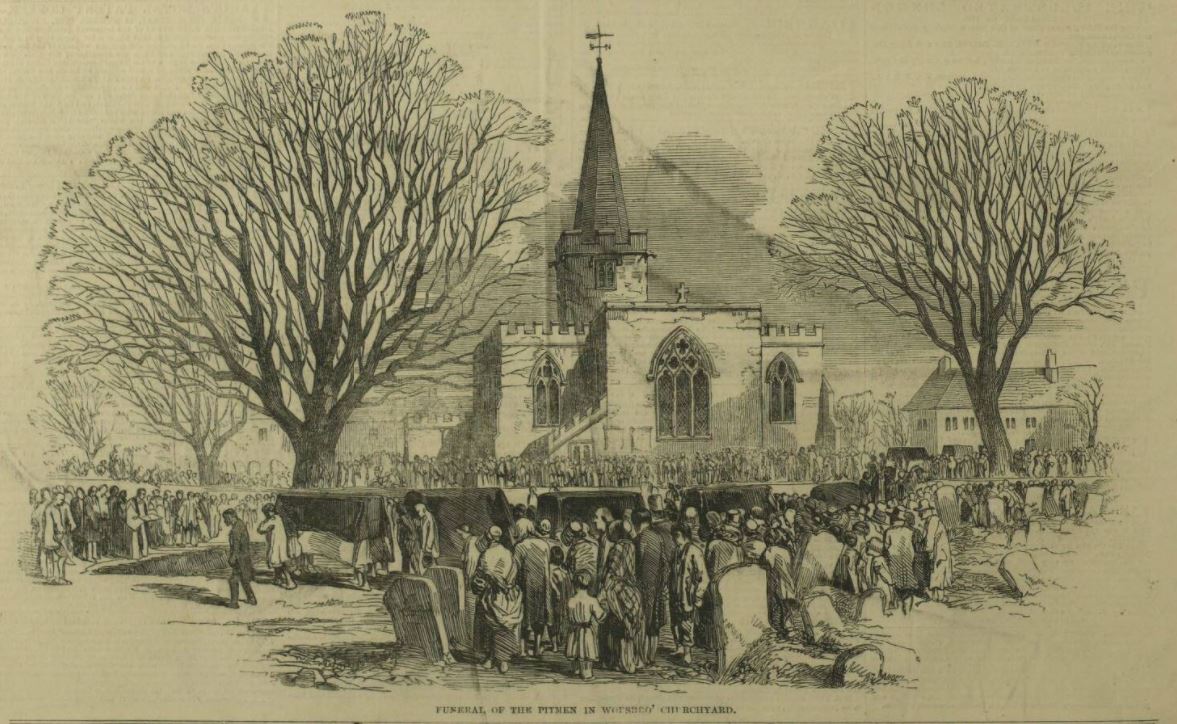

A colliery explosion near Barnsley as the Darley Main Colliery. No fewer than seventy-five lost their lives.

Funeral of the Pitmen in Worsbro Churchyard

A dreadful explosion at Ebbw Vale Colliery, Abercane in Monmouthshire. 371 men were in the pit at the time of the explosion and a large proportion of them were killed.

The terrible colliery explosion in Wales

Miner's Song

Our look at 19th-century coal mining through the newspapers also revealed an intense sense of community among the miners. Especially, during times of protests and strikes. Miners reported that they knew they could rely on their friends and neighbours for support in hard times. Miners were proud of their work. In 1870, The Cornish Telegraph published A Miner’s Song.