Despite Legal Challenges, CONSOL Continues Longwall Mining Beneath Pennsylvania's Ryerson Station State Park

By Max Graham

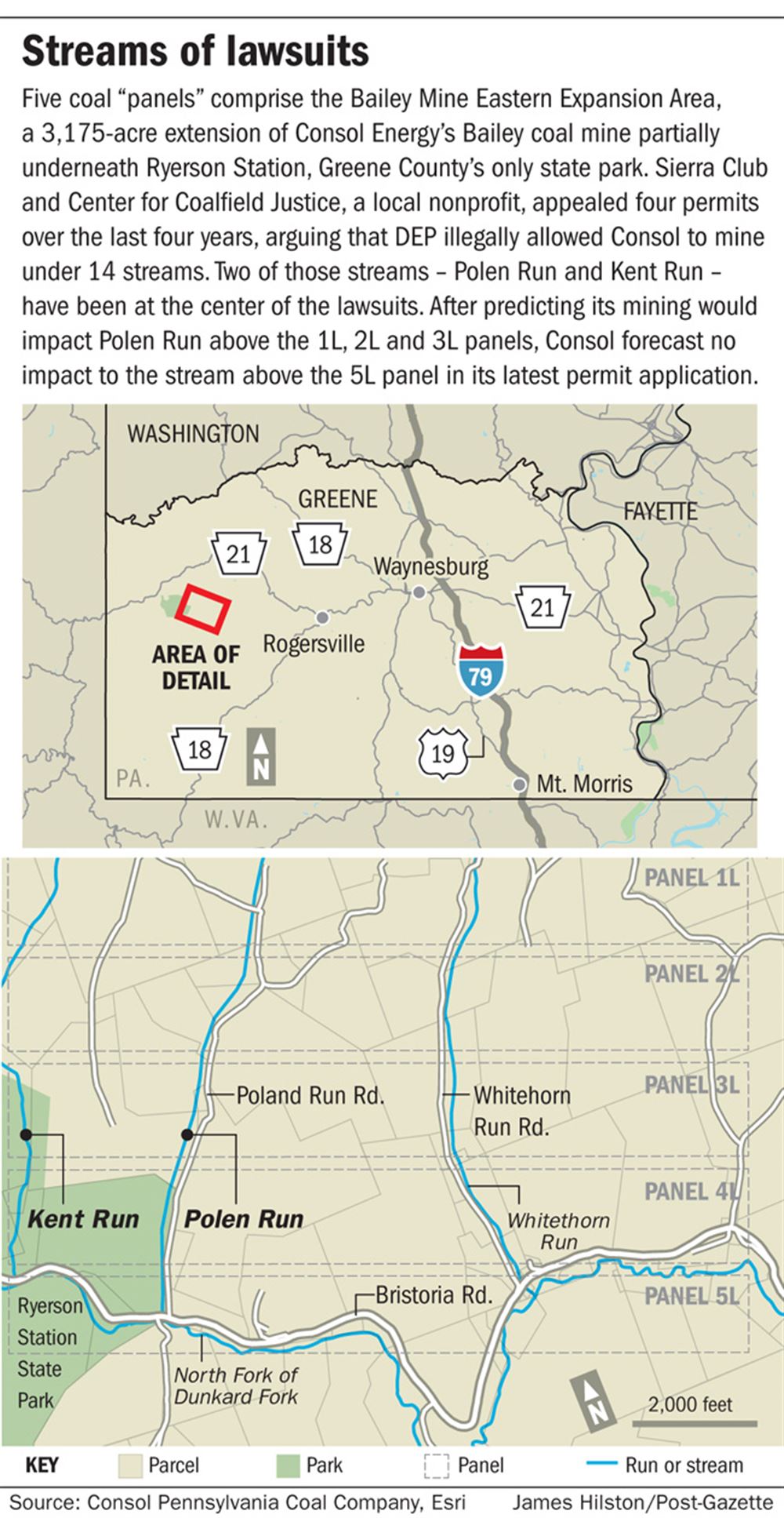

August 7, 2018 - CONSOL Energy repeatedly predicted in permit applications that its longwall Bailey coal mine in Pennsylvania would impact streams in and around Ryerson Station, Greene County’s only state park.

But it said the damage — caused by massive machines chewing through miles of underground coal seams — would not be permanent. The company outlined mitigation plans, promising full restoration of impacted streams over the six years it sought permission to mine in the area.

In its latest application, though, CONSOL predicted no damage would result from mining beneath Polen Run, which flows along Ryerson Station’s northeastern edge.

The change in tune came after the Environmental Hearing Board ruled in August — on an appeal by nonprofits — that the Department of Environmental Protection illegally allowed CONSOL to mine under two sections of Polen Run.

Since 2014, Sierra Club and the Center for Coalfield Justice have jointly appealed four DEP permit revisions that authorized mining under 14 Greene County strea Agreeing with their arguments for one of those appeals, the EHB for the first time decided that promising to mitigate damage is not sufficient to get a permit.

“When … the only way to ‘fix’ the anticipated damage to the stream is to essentially destroy the existing stream channel and streambanks and rebuild it from scratch … to issue [the permit revision] is unreasonable and contrary to the law,” Judge Steven C. Beckman of the Pennsylvania Environmental Hearing Board wrote in an August 15 opinion.

Kent Run in Ryerson Station State Park, Pennsylvania, is located above a controversial longwall coal mine. Kent and another stream in the park – Polen Run – have been at the center of legal challenges over the last four years.

Photo by Max Graham, Post-Gazette

Following the decision, DEP tightened regulations, effectively barring CONSOL – now CONSOL Pennsylvania Coal Company, a spin off from the parent energy company – from mining under another section of Polen Run.

Then CONSOL revised its permit application for beneath the last section of the stream, now anticipating no impact.

Despite the fact that photos and stream health analyses evidenced fractured bedrocks, pooling and flow loss caused by CONSOL in previously-undermined sections of Polen Run, Mark Haibach, a contractor for the Cecil-based conglomerate, testified on April 16: “I would expect that Polen Run … would maintain its natural range-of-flow conditions following mining; and if flow is maintained, then I would expect there to be no impact to the biological community.”

Since then, the legal battle over mining beneath Polen Run has continued, but the efforts to stop CONSOL have been unsuccessful. In May, the company undermined the last section of the stream.

Veronica Coptis, executive director of Center for Coalfield Justice, used to run along trails beside Polen Run and other threatened streams in the park’s east. She has spent the last half-decade fighting to protect those waterways from the ill effects of mining.

“Ryerson was one of the only places you could go to be somewhat removed from all the destruction going on in the rest of the county,” Coptis said. Now, “extraction is everywhere.”

Winding its way down sloped woods in northwestern Greene County, Polen Run is calf-high at its deepest point, and its banks grow no more than five feet apart.

Still, several species of small fish, including trout, and other aquatic life have found home there, and locals like Coptis have long enjoyed it as a source of refreshment.

Before she started running along Polen, Coptis “spent almost all of [her] time” at Duke Lake, a 62-acre reservoir in the park’s west.

In 2004, subsidence caused by CONSOL’s Bailey mine led to a breach in the Duke Lake dam, ultimately draining the lake. The Department of Conservation and Natural Resources sued CONSOL for the damage, reaching a $36 million settlement in 2013.

DCNR abandoned lake restoration plans in 2015 after determining the ground beneath the dam was still shifting.

In exchange for the money, CONSOL did not have to admit fault, even though a 2010 state investigation determined the company’s mine caused the damage. The company also received permission from DCNR to conduct longwall mining under the eastern portion of Ryerson Station — as long as it got a permit from DEP.

While litigation over the dam was ongoing, CONSOL submitted in 2007 a permit application for the 3,175-acre Bailey Mine Eastern Expansion Area. This addition consists of five longwall “panels” – rectangular reservoirs of coal, each 1,500-by-12,000-feet long.

Longwall mining — the most extractive mining method — requires narrow ventilation shafts and heavy-duty equipment: hydraulic “shields,” or ceiling supports, conveyer belts and massive mechanical shears. Mining an entire two-mile-long panel takes several thousand cuts, according to DEP.

The equipment moves through one panel at a time, from east to west in the expansion area. Following the shields, which prop up the earth overhead, the shears shave a panel’s width-wide “face.” As the shields and shears advance, they leave behind a void. Unsupported, the ground above sometimes sinks.

Known as subsidence, this phenomenon can cause houses to collapse, wells to breach and streams to run dry, as water seeps through cracks in the streambed.

Longwall mining impacted 315 structures and 39 miles of streams statewide between 2008 and 2013, according to a DEP report.

DEP lists on its website nine active longwall mines in Pennsylvania, all in Greene or Washington County.

The Bailey mine, opened in 1984, is one of three mines that comprise CONSOL’s Pennsylvania Mining Complex, the largest underground coal mining complex in North America. The Complex produces 28.5 million tons of coal annually and employs 1,700 people – about 300 in the eastern expansion area – according to CONSOL spokesman Zach Smith.

In 2014 DEP authorized longwall mining in the expansion area, except beneath two streams: Polen Run and Kent Run.

Headwater streams like Polen and Kent are most vulnerable to subsidence, as they are shallow and more likely to go dry, Coptis said.

Despite its initial concerns, DEP authorized, in a series of permit revisions over the last four years, longwall mining under several sections of Polen and Kent.

CCJ and Sierra Club appealed each revision, arguing that state regulations “do not authorize the Department to permit an activity where it predicts or anticipates that such activity will impair protected stream uses,” according to a post-hearing brief filed on Oct. 21, 2016.

CONSOL’s mining, the brief said, “will cause or has caused impairment.”

CONSOL claimed, in a post-hearing brief filed a month later, the nonprofits were calling for a “zero-impact standard,” which would unreasonably prohibit any activity that even temporarily disturbs a stream. The company argued the incurred damage should not qualify as pollution because the streams would be fully restored.

“We have an excellent track record when it comes to planned subsidence underneath streams,” Smith said in an email to the Post-Gazette. “We restore the streams to pre-mining conditions or better while maintaining the values and uses of the stream.”

As CONSOL advanced in the first panel beneath Polen, DEP surface subsidence agent Joe Laslo observed fractured bedrock in the stream and several cracks across Polen Run Road, according to a March 2015 email to DEP officials.

By August 2015 the stream had lost 3600 feet of flow, Laslo recorded in a 2016 DEP report.

The site of Duke Lake in Ryerson Station State Park in Greene County is now dry. It was drained in 2005 after cracks developed in a dam following longwall mining beneath the park.

Photo by Rebecca Droke, Post-Gazette

CONSOL claims the upper portion of the stream has been fully restored.

But nearly three years after being undermined, Coptis said, it still is not its old self. Plastic pipes replacing the damaged natural spring protrude from the hillside, and concrete weirs — designed to mimic ripples — jut out from the streambed.

In January 2017, the nonprofits won an emergency injunction for which they had petitioned a month earlier.

“The Department’s permit application review process was arbitrary, capricious, inappropriate and unreasonable,” Judge Beckman wrote in a Feb. 1 opinion.

When DEP clamped down – after the ruling in August 2017 that precluded mining where impairment is expected – CONSOL revised its application and, for the first time, predicted no impact on Polen, now in the fifth panel.

On March 7, DEP gave the green light. Shader said the department determined the mining “would not result in permanent flow loss and that the stream could be restored.”

Other state officials were wary of CONSOL’s forecast.

“The DCNR does not believe CPCC [i.e., CONSOL] has provided definitive data supporting their conclusion,” said John S. Hallas, director of DCNR’s Bureau of State Parks, in a Jan. 4 letter to Michael Bodnar, a DEP mining official.

CCJ and Sierra Club unsuccessfully sought another injunction.

In an April 24 opinion, Environmental Hearing Board Judge Thomas W. Renwand said the decision was a “close call” but the appellants did not meet the “high burden” needed to win.

“We do agree with the Appellants, however, that CONSOL’s prediction of ‘no impact’ is unlikely,” Judge Renwand wrote. Still, the impact would be “short-lived and minimal and restored.”

By May 10, CONSOL had fully undermined Polen Run in the fifth panel, according to the company’s June 20 motion to dismiss the nonprofits’ appeal.

The motion says the stream did not experience adverse effects from the mining. Coptis said CCJ is monitoring the stream weekly and has observed a few signs of impact. Still, she said, it is hard to know the extent of damage since it has been an especially wet few months.

CCJ and Sierra Club are proceeding with the suit.

Smith declined to comment on CONSOL’s operation beneath Ryerson Station given the pending litigation.

Still, the company plans to continue extracting earth. It estimates 27 years worth of coal remain beneath Greene and Washington Counties, according to Smith.

For Coptis, that is a scary thought.

“If mining continues advancing at the pace it is, almost the entire watershed will be undermined,” she said.

“The park is a place that’s so hard to describe in words. I just can’t imagine not raising my daughter there. But who knows how much water will be left.”