The Upper Midwest's Resilient Coal Industry

By Sam Easter

January 3, 2020 - Leon Weisenburger plans to retire a coal miner.

He’s bounced around the country, working in coal in the 1990s before taking a high-ranking city job in Garrison, N.D., and following his wife, a nurse practitioner, to California. Now he works heavy machinery at the Coteau Freedom Mine, where he plans to stay for another 15 years. That’s about an hour’s drive from Underwood, where Weisenburger is the City Commission president—functionally, the mayor.

Speaking by phone just hours before a 12-hour, overnight shift, he described a city where the economy is entirely dependent on coal. Underwood, Weisenburger estimates, has somewhere between 30% and 40% of its residents either working for a coal mine or a nearby coal-fired power plant. The town exists because of coal, and corporate coal dollars take good care of it, Weisenburger said, standing ready to help with the city’s daily life. The city’s website points out that the local golf course is “the result of a unique joint effort” between the city and a nearby mining company.

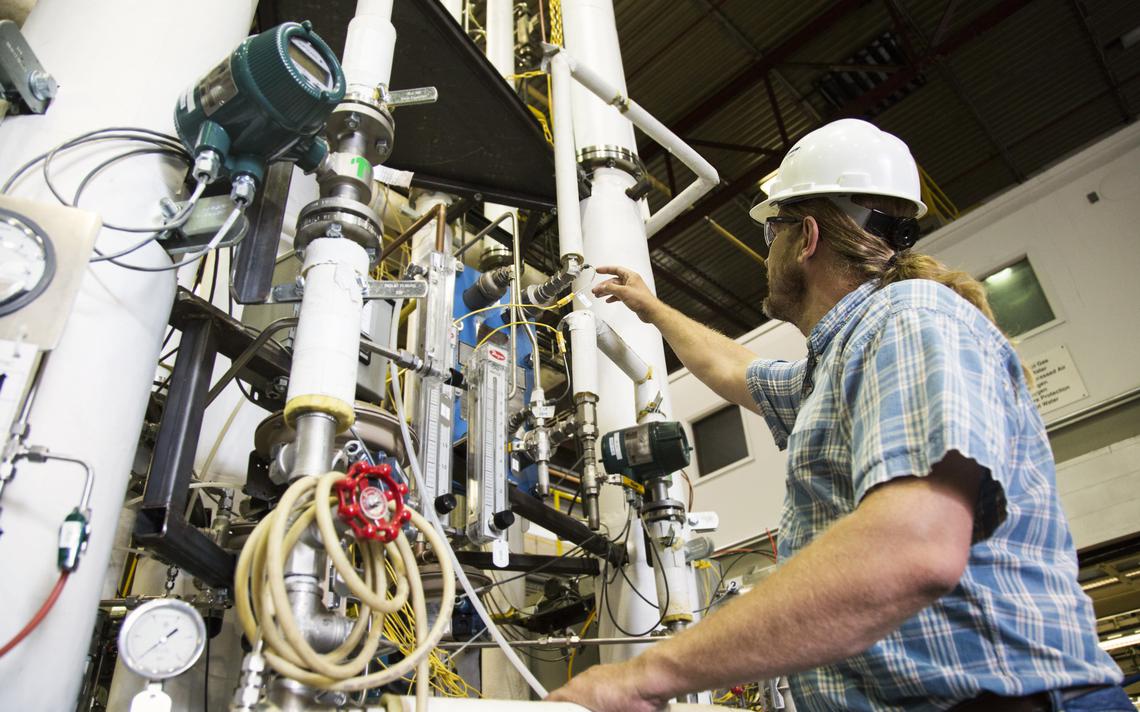

The interior of the Energy and Environmental Research Center at the University of North Dakota during early 2018 tour. Pictured is the center’s apparatuses for testing carbon capture methods.

Photo: Kari Suedel / EERC

“When they talk about ‘go green,’ and this and that, it is concerning to coal miners,” Weisenburger said. “But what they don’t understand is that fossil fuels — that’s what built this country, fossil fuels did, and they’re forgetting that it can’t go away. It’s just a fact of nature that it will always be around, because it can be around with the flick of a switch, where wind-generated (energy) cannot, and neither can solar.”

Although the coal industry is slipping in many parts of the country—and renewable energy advocates are hard at work making wind and solar just as dependable as coal—the Upper Midwest’s coal industry has been resilient. Federal data shows that the coal mining industry employed more than 175,000 nationwide in the mid-1980s, which has since fallen to about 53,000 as of October, the result of pressures from not just renewable energies and regulations, but inexpensive natural gas and automation as well.

But in places like North Dakota, the coal model is propped up by a relatively unique economic arrangement: lignite coal is mined immediately adjacent to coal-burning plants, which then produce electricity for consumption within state borders and beyond. Widely referred to as a “mine-mouth” arrangement, it’s a way to drastically cut costs in coal power production.

“If it weren’t for the fact that we were exporting electricity, we probably wouldn’t have a coal industry, because lignite (coal) in and of itself is not competitive if it has to be transported large distances,” said Dean Bangsund, a research scientist and economist at North Dakota State University. Not only is the water content higher and the energy content lower, but the transport itself can increase prices.

And there’s plenty of coal to last. Jason Bohrer is president and CEO of the Lignite Energy Council, a Bismarck-based group that advocates on behalf of the coal industry. He said that North Dakota currently has an 800-year supply of “economically recoverable” coal for the state’s current coal-fired plants.

The question, then, is about what the future will bring. There are other power sources gaining ground in the marketplace, like inexpensive natural gas and a growing renewable energy market. Ben Fladhammer, a spokesman for Minnkota Power Cooperative, said the company’s current power source portfolio is about 60 percent coal, down from 80% to 90% coal in the late 2000s, which comes on the heels of “tremendous” wind development in the upper Midwest.

But a looming question for the coal industry is regulation. Coal has, historically, been a significant, if recently declining, source of carbon emissions in the U.S., with 1.1 gigatons in national projected emissions for 2019, according to the Global Carbon Project. Those emissions are increasingly at odds with movements to stem the projected effects of man-made climate change.

That tension stole the political spotlight during President Barack Obama’s administration, when the Clean Power Plan — a sweeping set of regulations meant to clamp down on emissions — called for steep reductions in carbon emissions around the country. In North Dakota, cuts to emissions would have been particularly steep, and Attorney General Wayne Stenehjem sued Obama’s Environmental Protection Agency in 2015 — making North Dakota one of many states to take issue with the plan, which was repealed in 2017 under President Donald Trump.

“The thing that is going to put the biggest pressure on the coal industry going forward is issues that deal with carbon (emissions),” Bangsund said. “There is a considerable effort underway right now to look at CO2 capture as a means of making lignite-sourced electricity viable in a carbon-constrained economy.”

A lot of that work happens at places like the Energy and Environmental Research Center at the University of North Dakota. The group bills itself as a global leader on cleaner energy, working specifically on the kinds of carbon-capture technology that can prolong coal power’s viability under tighter regulations.

“In terms of timing, when these regulations come out…we simply don’t know,” said Josh Stanislowski, the EERC’s director of energy systems development. “A lot of it can be tied up in legal challenges, but a lot of it is tied up in politics, and the (2020 election) is going to play a big role in that.”

One of the most ambitious attempts to get ahead of the carbon capture curve is unfolding in North Dakota, where Minnkota is pursuing “Project Tundra” — a $1 billion carbon-capturing upgrade to the Milton R. Young Station, a giant coal-fired plant near Center, N.D. Dan Laudal, environmental manager with Minnkota, said that the project is in an advanced planning stage, seeking out investors with an eye to launch construction by 2022 or 2023. If completed, Laudal said, it would be the largest “post-combustion” carbon capture facility in the world.

“It’s certainly not at a point where we can call it a certainty, but I would say it’s transitioned out of the research domain,” Laudal said. “The most unknown piece of all of this is whether or not we can bring in financing.”

And for now, the North Dakota coal industry appears healthy. According to a January report co-authored by Bangsund, the North Dakota lignite industry was growing its compensation through at least 2017 though with employment “edging down” in those years, as Bangsrud described it. It’s the most recent data on the local industry Bangsund has at his disposal.

“So we have some mixed messages in terms of the economic footprint of the industry,” he said.

That’s an important issue not just for the industry, but for the cities and towns that depend upon it.

“The majority of the people that live in these smaller communities work at the coal mines, and the coal mining industry has very good wages and benefits,” Weisenburger said. “If it wasn’t for the coal mines, these towns would not exist.”

(1).jpg)

The interior of the Energy and Environmental Research Center at the Unversity of North Dakota during an early 2017 tour. Pictured is the center’s apparatuses for testing carbon capture methods.

Photo: Kari Suedel / EERC