View From the Rails: Train Engineer Chronicles 25 Years of PRB Coal

March 4, 2020 - There’s a rhythm to every landscape that, if you watch it long enough, transcends the annual seasons. For example, the prevalence of raptors along the 150-mile rail route from Wyoming’s Powder River Basin to the Nebraska border seems to cycle every five years or more. Except for the owls.

Union Pacific locomotive engineer Alan Nash uses his Twitter account — @VernChronicles — to post dozens of photos of the agriculture and coal industry in the Powder River Basin.

Photo: Dustin Bleizeffer, WyoFile

Two decades ago owls were all over, swooping in behind coal trains as they rattled mice out from under the wooden rail ties. You don’t see them much today, though, said Union Pacific Railroad locomotive engineer Alan Nash. Maybe it’s because the railroads switched to cement ties years ago, or critters have simply moved away from the bustling rail line.

Nash, who has regularly traveled the 150-mile route for more than 25 years, says it’s a banner year for pronghorn in the southern Powder River Basin. The Rochelle Hills elk herd has been appearing in full force near the entrance of Peabody Energy’s North Antelope Rochelle mine — the largest coal mine in the world. The ungulates seem to appreciate mine properties that have been reclaimed with native grasses and shrubs, he said.

Nash notices changes at the coal mines, too, where production is in historic decline.

A few years ago, Nash started packing a camera with him to chronicle the pulse of life and industry along the rails, capturing images of eagles and ungulates, sunsets and sunrises juxtaposed by grain silos and giant coal shovels. Each month, Nash posts dozens of scenes from his beloved #WyoBraska route to Twitter under the handle @VernChronicles. It’s a view of the Powder River Basin, and a massive mining complex and an industry in transition that few get to see up close.

“I just don’t think there’s a lot of relatability out there in the public unless you’re directly involved with the industry itself,” Nash recently told WyoFile over a cup of coffee at Penny’s Diner in Bill. “I guess that’s part of why I tweet a lot about what I do. This is affecting everybody — more directly in Wyoming and definitely more directly in Gillette. But it reaches out far.”

Lately, Nash — or “Vern,” a nickname from his childhood in Nebraska that just kind of stuck — has developed a small but devoted following on Twitter. Among his followers are many who write about the coal industry.

Taylor Kuykendall reports about the coal industry for S&P Global Market Intelligence. He said Nash’s frequent postings of Powder River Basin images offer a rare glimpse of the rail operations, coal mines and wildlife of the region.

“Interacting with Alan through social media is an excellent way to be reminded of a very personal element behind an industry often talked about in terms of tons or dollars,” Kuykendall said. “I feel like his clear-eyed take on the realities facing the coal sector — coupled with his reminders of the people that the transition is impacting — is refreshingly helpful when thinking about the broader energy transition in the U.S.”

One of his primary motivations, Nash said, is to chronicle an impressively intricate industrial complex that appears to be in the throes of a foundational decline, and the people who have a direct stake in the transition. When a mine in the Powder River Basin loses a customer contract, for example, it requires fewer rail trips. Running fewer trains, Nash said, threatens the livelihoods of railroad crews from Wyoming who haul loads to Nebraska for distribution to places like Illinois and Arkansas.

Nash’s dispatches offer a human, qualitative window into coal’s decline. Industry data hammer home the quantitative reality of the shift. From 2008 to 2019, the pulse of coal out of the Powder River Basin has slowed from about 80 trains per day to 50 trains, according to railroad industry data. Trendlines point to a continuing decline in PRB coal as utilities across the nation shift to natural gas and renewables.

Compounding anxieties among rail workers is a proposal to switch from two-man to one-man crews.

“We have the coal industry itself on the decline, and then we’re looking at contract negotiations [between unions and railroads] right now that are looking at one-man crews. So, I mean, they’re kind of dogpiling on us right now,” Nash said.

‘It’s the only thing I’ve got’

The PRB coal industry is primarily served by the Union Pacific and BNSF Railway railroads. The Dakota, Minnesota and Eastern Railroad tried for years and failed to get a line into the prolific coal complex.

Nash, 57, took some college courses after graduating from Scottsbluff High School. He hired on with the Chicago & North Western railroad as a conductor in 1993 and became an engineer in 1994. Union Pacific bought C&NW in 1995. “I’ve worked from the South Morrill, Nebraska terminal the whole time,” Nash said. “All on the coal line.”

A pair of locomotives at the North Antelope Rochelle Mine.

Photo: Alan Nash

Railroad workers typically earn $55,000 to $95,000 annually, sometimes more, according to Union Pacific and BNSF Railway. Nash figures he’s got five to 10 years before retirement. But there’s a growing sense of uncertainty among rail workers on the Powder River Basin and other coal routes across the country.

“It’s a good-paying job for where I live, and it’s the only thing I’ve got,” Nash said. “If something happens here, I’m not going to fall back on anything that comes close.

“We’re filling a need for an industry and we’re getting paid well for it,” Nash continued. “I’ll never complain about what I get paid. Never. This job’s provided me with a lot of things I’ve never imagined I’d be able to do. The company, yeah, I get a little frustrated with them sometimes. But, you know.”

Railroad unions don’t seem to be as effective as in years past, Nash said. Many blame the unions for a deal struck in 2005 that left the door open for railroads to eliminate jobs via automation. Wyoming is among several states considering legislation that would set train crews at no fewer than two workers.

Coal is big business for U.S. railroads. Historically, many railroads earned more from shipping coal than anything else. Recently though, the industry is earning more from freight and chemicals than from coal. According to the Association of American Railroads, trains shipped 518 million tons of coal in 2018 compared to 878 million tons in 2008, a 41% decline.

The sun sets over the rails near Morrill, Nebraska, in a shot that was featured in Nebraskaland Magazine.

Photo: Alan Nash

Rail industry analyst Jim Blaze recently looked at the coal landscape for American railroads and concluded that the decline in coal mining and coal usage at power plants will fundamentally change railroads. Railroads like BNSF Railway, where coal accounts for nearly 18% of its overall traffic, and Union Pacific, where coal accounts for 13.4%, have made strides in cost-cutting along their coal routes, Blaze wrote in Freight Wave News, an industry publication. “But can they continue cost cutting indefinitely?” he wrote. “There will be practical limits.”

“That’s the thing with this whole coal issue,” Nash said. “We all hired out with that number of 200 years of coal in our head, you know. None of us thought they’d ever come up with something else to replace it cheaper, so none of us were mentally prepared for this.”

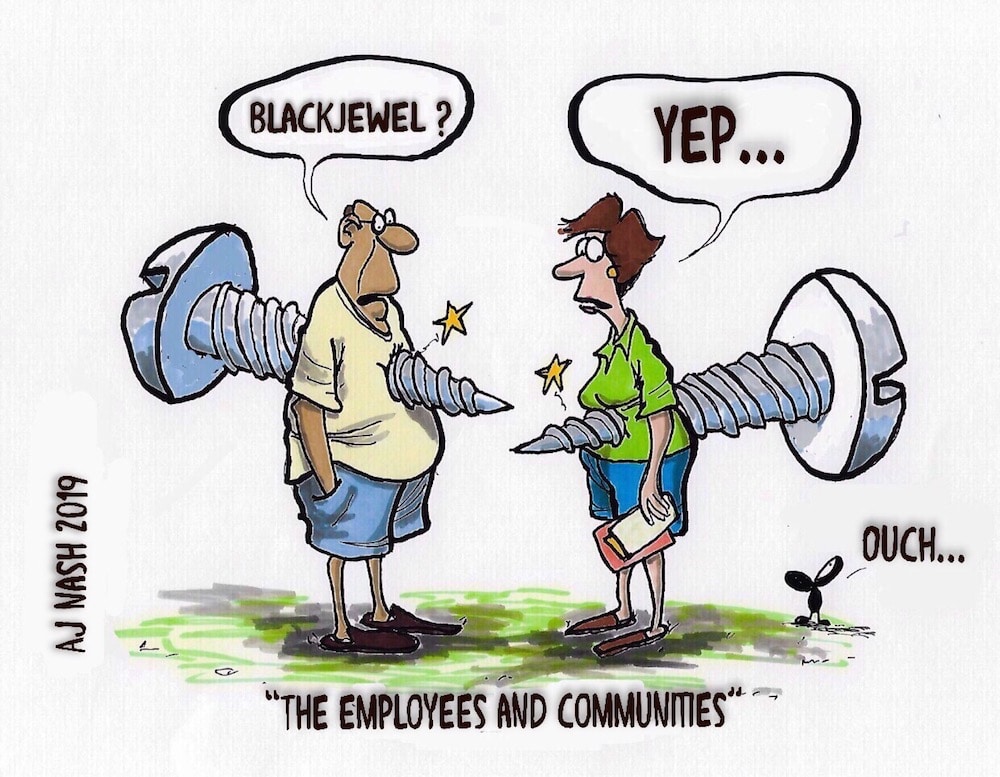

A Cartoonist, Critic and Coal Advocate

Before he began chronicling eastern Wyoming and western Nebraska with his camera, Nash used his wit and drawing skills to skewer the absurdity of politics, as well as the divide between corporate and blue-collar life in the rail industry. He began publishing editorial cartoons for a pair of Nebraska newspapers in 2002 before expanding his work to several industry and union publications.

His work has been recognized among the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists’ “Best Editorial Cartoons of the Year.”

A few times, though, his cartoons got him sideways with corporate higher-ups. There was the one in 2007 depicting CSX Railroad employees chained to a prison wall, victims of the company’s alleged culture of intimidation. Another one in 2009 criticized Union Pacific for its furloughs. To help smooth things over, Nash agreed to compose a series of cartoons for the company’s employee safety program.

Nash said he’s not shy about asserting his right to free speech, although he admitted it’s good to know his limits with the company. These days, Nash uses his drawing pencils to sketch canines, including an occasional portrait for dog-owners he knows.

Along with being a train engineer and photographer, Nash draws cartoons.

Photo: Alan Nash

Many coal industry reporters who follow his work are based far from eastern Wyoming, the epicenter of American coal mining. The region supplies 40% of the nation’s coal. Although they understand the scale of operations here, Nash’s Twitter photos, and his interactions with those who follow him, are ways to help people connect to the region and coal industry workers.

One of Nash’s Twitter followers, E&E News reporter Heather Richards, formerly the energy reporter for the Casper Star-Tribune, described him as “stubbornly kind and warm” — a rare commodity on a social media platform that’s not known for civility.

“Alan is a really nice dude,” Richards said. “I think that’s the main draw to him. But he also kind of takes everyone along with him to coal country, and his daily posts, his cartoons and tweets make the industry personal, knowable.”

Nash said he didn’t set out to become a spokesman for coal. In fact, he loves to share stories and critiques from a broad range of perspectives. But he’s happy that his photos have engaged people with the industry. Nash said that, mostly, he’s an advocate for workers in an industry that’s often misunderstood and demonized.

“None of us got into this to change the climate,” Nash said. “We’re not evil people. We’re not dragons to be slain.”

For many of the tens of thousands of workers who have toiled to help power America with coal — from the mine, to the rails, and to power plants — they can’t simply switch to a new career that pays the same or allows them to remain in their hometowns.

“I understand the renewables thing. I get it. But I don’t think a lot of people understand the transition that needs to happen.”