|

Signature Sponsor

June 18, 2025 - We’re more than a hundred feet under Beckley, West Virginia, when the lights go out. One minute, I’m scanning the roof bolts and support timbers above my head, and then, with a thunk, there’s just . . . nothing. Nothing but the faint drip of water down the rock walls. Gerald Lucas asks me to put my hand out. I can’t see it, or him. It’s only 58 degrees—the temperature underground is constant all year—but I shiver a little. Oblivion is disorienting. “That’s how dark it is inside a coal mine,” Lucas says. He waits a few seconds, then thumbs the power switch back on. Lucas is 74, with close-cropped white hair, a neatly trimmed goatee, and a voice that curls around vowels in a way you don’t hear much anymore. That he can do this at all—flip a switch—is something he never takes for granted. Back in 1972, when he first picked up a No. 4 coal shovel and entered the mines like his father before him, roughly half of America’s electricity came from coal. He worked underground for the next 45 years, often twelve hours a day, six days a week. It was one of the world’s most physically brutal, dangerous jobs. He still bears the scar on his neck from a piece of machinery that nearly strangled him. But every day brought a new sense of discovery, and eventually mining got into his blood. “Every time you take the coal out of there,” he says, “you’ve been somewhere no one’s ever been before.” Then the world changed, and miners like Lucas had to change with it. Energy companies have increasingly shifted toward natural gas and renewable technologies (solar, wind, and hydroelectric power), while coal production in the United States has plummeted. It now accounts for less than 20 percent of American electricity. While this has been good news for the environment—coal is a major source of carbon emissions—it has also eliminated tens of thousands of jobs. Communities across the Appalachian coalfields in West Virginia, Kentucky, and Virginia have been forced to adapt, and many of them, like Beckley, are finding new hope in tourism.

Photography by Gregory Miller

When Lucas dons his blue coveralls and hard hat these days, it’s as a guide for Beckley’s Exhibition Coal Mine, which last year drew roughly 55,000 visitors and made almost $1 million in revenue—a vital boost for a town where more than a quarter of its 16,600 residents live in poverty. But the transition to tourism hasn’t always been seamless or easy. When Lucas retired from his government job as a mine safety inspector six years ago, the average salary for a veteran miner approached six figures. His federal benefits weren’t enough to cover his expenses, so he had to find another job. Now he makes $10 an hour. “If you don’t work in the mining industry,” he says, shaking his head, “you don’t make any money.” Still, Lucas takes great pride in teaching people about the history of American mining (in 2023, he even met country star Brad Paisley, who filmed a music video underground). He ushers visitors into small carts, or “mantrips,” steers them into the mine, and shows them artifacts from years past, such as the old canary cages used by miners to detect poisonous gases and the carbide headlamps miners wore in the early 20th century. “Most people that come through here have no clue where their power comes from,” he says. “They have no clue what those miners went through just to provide that electricity.” In this part of the world, it all begins with geology. Almost nothing in southern West Virginia is flat. Even in the larger towns, houses teeter on the hillsides and the roads wind through valleys wreathed in fog. It’s as if God crushed this part of America in his fist, compressing ancient swamps into jagged shale and sandstone ridges. These are among the oldest mountains on earth, and the New River, which carves through them, is the world’s second-oldest major waterway (the first is the Nile). Some of the planet’s richest seams of high-quality, bituminous coal run underneath this imposing terrain.

Photography by Gregory Miller

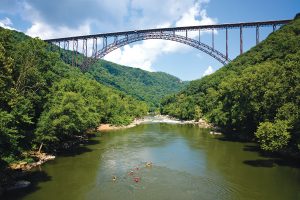

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, coal mined from the New River Gorge powered American industry. Without it, there would have been no electricity, no steel for skyscrapers, no fuel for battleships. But that came at a heavy cost to the land itself. A frenzy of mining and logging stripped this region bare starting in 1873, when the Chesapeake & Ohio Railway connected the upper and lower gorge, and coal camps and boomtowns sprang up nearly every half mile along the river. Looking out over the New River Gorge today from its soaring single-arch steel bridge (a half-hour northeast of Beckley), it’s hard to imagine the heart of America’s newest national park as anything other than pristine wilderness. The dramatic landscape that once made this region so appealing to extractive industries now makes it a haven for ecologists and outdoor adventure-seekers. The gorge plunges from roughly 900 feet to 1,400 feet at its deepest point, creating dozens of microclimates for diverse plant and animal species. Steep drops on the New River and its neighbor, the Gauley, also form some of the region’s most thrilling Class IV and V rapids for whitewater enthusiasts. For hikers and mountain bikers, there are a hundred-plus miles of trails cross-hatching the dense forests, and dizzying sandstone cliffs are perfect for rock-climbing and bouldering.

Photo by Holly Wolff

Remnants of the park’s industrial history still exist, though, if you know where to look. Visitors can explore the old coal tipple at Nuttallburg, owned by Henry Ford, and the coke ovens in the lower gorge. The boomtown of Thurmond, once only accessible by rail, looks much the same as it did in 1910, when it boasted several hotels, department stores, and banks. (Legend has it that one poker game at Thurmond’s Dunglen Hotel lasted 14 years.) As mining technology advanced in the mid 20th century, the coal companies began to move on. Starting in the late 1960s, several whitewater-rafting outfitters entered the scene. This marked the first notable shift from coal extraction to tourism infusion, and it came with growing pains. Running a viable rafting business required river guides to bus visitors to and from the river, often through fairly small, quiet communities. “There were people who didn’t like the rafting industry at all,” says Visit Southern West Virginia Director Lisa Strader, who has worked in tourism for more than 30 years and recalls some locals posting protest signs in their yards. “It was hit-and-miss there for a while, and to be honest with you, sometimes it still is.”

Photography by Gregory Miller

When New River Gorge was designated a national park in 2020, and the number of visitors nearly doubled in one year (from around 300,000 to more than half a million), it could have come with similar pushback. But according to David Bieri, the park’s supervisory ranger, it hasn’t. “All the local communities in the area are the ones that pushed for this to become a national park,” he says. “And we’re seeing a lot of local groups developing trails for hiking, rock climbing, and mountain biking in areas outside the park.” Families in former coal-mining communities are often the ones driving conservation efforts, too—even volunteering to help pick up trash during government shut-downs—because they’ve seen how important the park is for their long-term survival. National-park enthusiasts, when compared with other visitors, tend to come to the gorge from farther away, stay longer, and pump more money into local businesses. More than 1.5 million people visited New River Gorge last year, almost three times the number of visitors to Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky and roughly the same number as visited Shenandoah National Park in Virginia. The spike in tourism pumped almost $100 million into West Virginia’s economy.

Photography by Gregory Miller

West of the national park, several of the state’s civic leaders and entrepreneurs have also found creative ways to work with coal, timber, and gas companies to turn unused acreage into tourism hotspots. One of the largest and most successful projects has been the 1,100-mile Hatfield-McCoy trail system, a multi-loop spiderweb for ATVs, UTVs, and other off-roading vehicles that cuts through nine counties in some of Appalachia’s most rugged wilderness—. It’s the only off-roading trail system of its size east of the Mississippi, and more than 80 percent of the 100,000-plus riders who use the trails come from other states. When Jeff Lusk, executive director of the Hatfield-McCoy Regional Authority, explains the importance of projects like the trail system, he’s careful not to present these efforts as offering one-to-one replacements for coal jobs. Rather, they create an environment in which new types of small businesses can grow, and those businesses in turn can create jobs in hotels, cabins, restaurants, gas stations, and equipment rentals. All of this allows former coal towns to regain their strength. “A community has to have people, and a job translates into people,” Lusk says. “It translates into somebody filling up a vacant house, mowing the grass. And maybe you get really lucky, and they’re a young couple, and they send a kid to school, and now, really, that’s a win-win, because that lets your little school continue to exist in your community.” The effects ripple outward in all sorts of indirect ways, and that gives Lusk a lot of hope.

Photography by Gregory Miller

“This was our past, and it’s going to be a part of our future,” he says of the energy economy. “There’s going to be coal mining going on here for the next 100 years. But we can also do this, and this can be a different thing.” There are many parts of working underground that Tony Basconi, another former miner who now works as a guide in Beckley, does not miss about his 40 years on the job. He doesn’t miss the toll it took on his body, which resulted in two knee replacements, a blown-out shoulder, and carpal tunnel in his fingers. He doesn’t miss getting up at 3:30 on winter mornings to drive to work for a 12-hour shift. He doesn’t miss all the time he spent away from his wife and three kids.

Photography by Gregory Miller

What he does miss is the camaraderie. “You worked around guys that you trusted with your life,” he says. “It takes us all to make it go. I gotta watch out for you. You watch out for me.” That same spirit inspired three-time Grammy winner Bill Withers’s 1972 hit song, “Lean on Me,” which came from his memories of growing up in Beckley, where his father mined coal. “My family didn’t have a refrigerator, and the people across the street from us didn’t have a phone,” Withers once told an interviewer. “So we helped each other. They gave us ice, and we let them use our phone.” This summer, Beckley will host its fourth annual Bill Withers Festival, as well as a host of other celebrations. “If you understand the coal history of our region as you travel,” Lisa Strader says, “everything else is going to make more sense.” But she and others in her industry are excited for this new era, in which dozens of small businesses are thriving—businesses that aren’t subject to the boom-and-bust cycle of energy extraction. Tony Basconi has watched tourism change communities like his. “I’ve definitely seen business pick up,” he says, and he expects that trend to continue. At least one new hotel has opened to accommodate more visitors, and the Dish Cafe in downtown Beckley just cut the ribbon on a second location. But despite these positive steps, Basconi never wants the work of miners like him, and generations before him, to be forgotten. He understands that coal can be a divisive issue—“I want clean air and water, too,” he says—but he still believes it’s an important part of American history. When he meets visitors, he wants to give them a tour of the mine. To tell them about a way of life that once powered America. And to answer their questions about a job most can’t imagine. More than anything, he says: “I just want them to respect it.” From Coal to Cool The Kentucky Wildlands Virginia Coal Heritage Trail Bridge Walk Endless Wall Trail Exhibition Coal Mine & Youth Museum Hatfield-McCoy Trails New and Gauley River Adventures Tamarack Marketplace Theatre West Virginia Adventures in the Gorge This article appears in the Spring 2025 issue of Southbound. |

|