|

Signature Sponsor

Why the World Cannot Quit Coal - Part 2

June 19, 2025 - Coal India has more than 300 coal mines across the country, and it is building more. The government expects domestic coal production to rise 6 to 7 per cent annually to reach 1.5bn tonnes by 2030.

The company is reopening almost three dozen defunct coal mines, and has a further five greenfield coal mines in the pipeline. Prasad, a mining engineer by background, expects that India’s coal use will peak around 2035.

“Gradually the share of coal will decline in the energy mix of the country and gradually we are also going into diversification,” says Prasad.

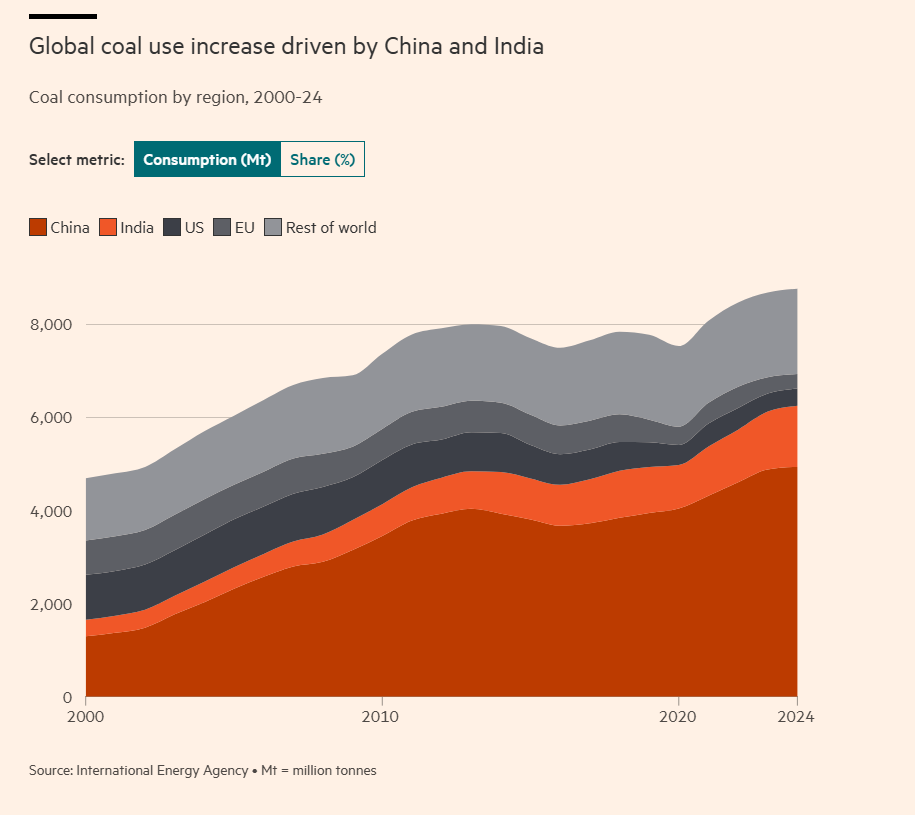

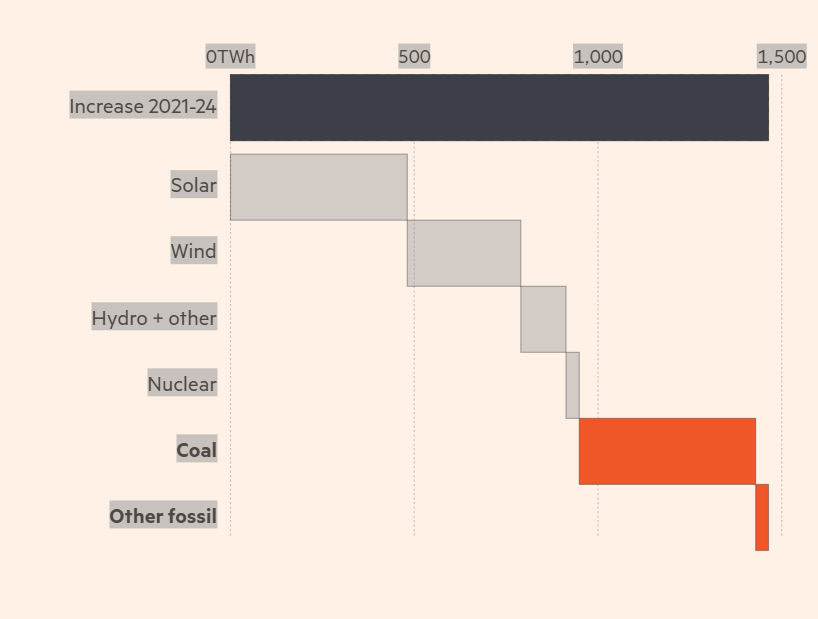

In China, the country’s race to electrify large sections of its economy, from cars and trains to factories, has meant that power demand has been growing faster than its economy since 2020. Over the next three years, China will need to add a Canada’s worth of electricity each year, to keep up with the surge in demand.

Coal production has stayed robust in places like Shanxi, a landlocked northern Chinese province of around 34mn people, which accounts for a quarter of Chinese coal production. The sector contributes about 30 per cent of Shanxi’s economy and is responsible for about 3mn jobs.

Wang Xiaojun, a 51-year-old climate activist from western Shanxi, says that when he was young, one of his jobs was to buy and carry coal for his family to use for cooking and heating. Since the 1980s, when coal became pivotal in fuelling China’s economic rise, most locals accepted “polluted air, polluted water, polluted soil, polluted lungs” as part of life, he says.

“As middle school kids, or later on as college students, we did morning exercises in the smog. And couples would not be surprised or upset about their wedding clothes becoming dirty with [coal] dust just after a few hours,” Wang says. “We all thought development had its cost. Some people had to get rich first, and China had to develop and get out of poverty first.”

Today, Shanxi is in some ways unrecognisable from those days, following the closure of thousands of mines over the past 15 years and the rapid build-out of renewable energy. But coal reliance has not lessened as much, or as fast, as many had hoped.

The central dilemma facing officials in Shanxi is how to speed up the transition away from coal without sparking mass job losses and potential social instability. Since 2021 local officials have explored a diversification strategy, investigating as many as 14 new industries to help alleviate the reliance on coal.

Coal production has been steady in recent years, however, and last year seven new coal mines opened in Shanxi, according to state media reports.

The biggest problem, Wang says, is that the population of Shanxi is not ready for a structural economic change.

“We’re not only talking about the economy, we’re talking about society,” Wang says, noting estimates that as many as 1.5mn people in the region could lose their jobs in the next five years. “Millions of people losing their jobs is not just a nightmare for Shanxi, this could be a nightmare for China.”

The challenge of how to keep jobs and provide livelihood for communities that are currently supported by coal is one that is replicated around the world.

As China’s electricity demand keeps rising, its coal consumption may continue to rise in absolute terms, even though it is shrinking as a percentage of power generation.

However, Li also notes, more optimistically, that China’s world-beating renewables and EV sectors have driven down the cost of these technologies, and that Xi appears to be “tying his climate legacy to industrial competitiveness”.

“He is telling everyone ‘we have a world leading solar, wind and electric vehicle industry’. That is how he sees climate progress now, and increasingly that is how the rest of the world sees climate progress,” says Li.

How soon the world will reach peak coal — if ever — is still being debated. But its climate impact is clear: coal accounts for 30 per cent of carbon dioxide emissions since the industrial revolution. On top of that, coal mining is a significant source of methane, a potent warming gas.

“I end up being rather frightened of what the future looks like,” says Helm, the Oxford professor. “Everyone agrees we are on an unsustainable path . . . But they are not prepared to accept the consequences.”

“There is no peak coal,” he adds. “The rate of growth will slow down. But if we carry on burning on the current level of coal, that is still a disaster.”

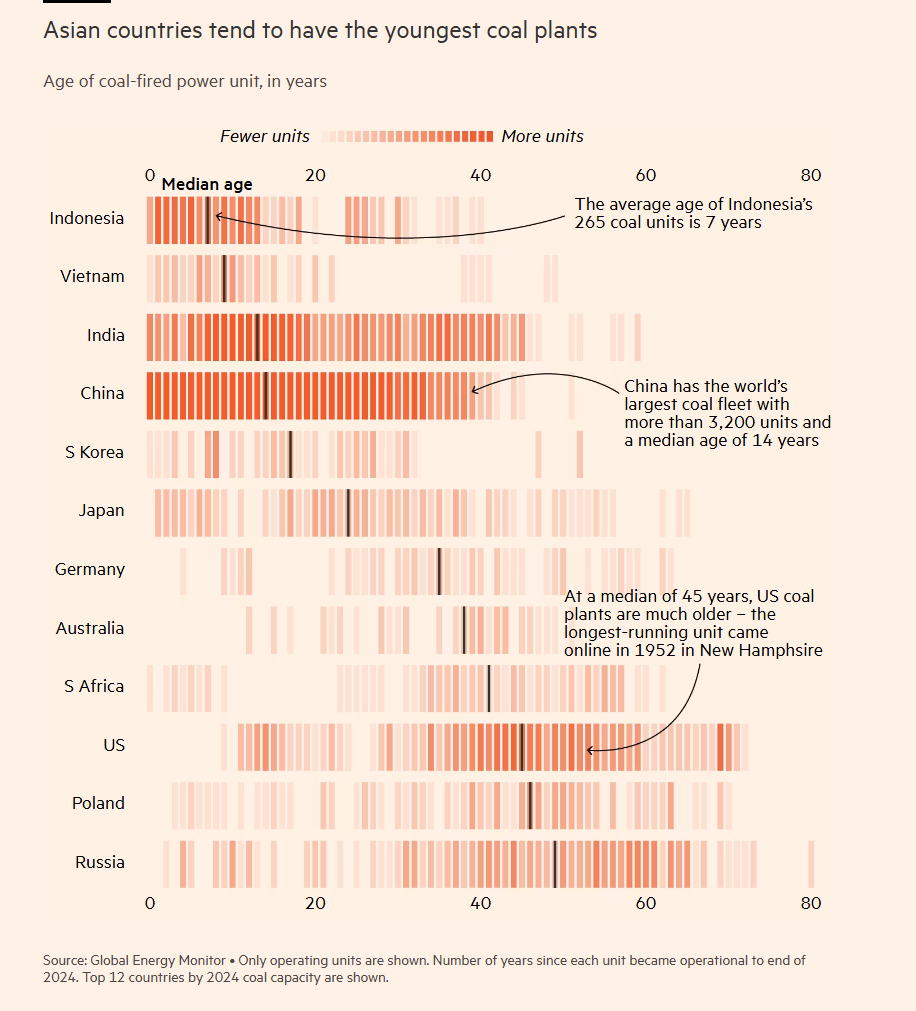

One of the gloomiest facts about coal’s future is the newness of the fleet of coal-fired power stations across Asia.

“There is a huge stock of existing coal plants that have already been built. And in a lot of cases, it is cheaper to run existing coal plants than to build anything new,” says Nat Keohane, president of the Centre for Climate and Energy Solutions.

He is working on an initiative, the Kinetic Coalition, that plans to fund the closure of coal plants using carbon credits.

Official estimates from the IEA show that coal use will plateau over the next few years, potentially peaking around 2027.

For Alvarez, the IEA analyst, his current model shows coal consumption increasing slightly over the next few years. “We don’t see coal really declining,” Alvarez admits. “It will probably peak before 2030 — but not tomorrow.”

One group of forecasters who reviewed the IEA’s record on coal, found that it consistently underestimated coal demand and predicted that there is a 97 per cent chance that Chinese coal consumption in 2026 will be greater than the IEA’s forecast.

Michael Story, director of the Swift Centre for Applied Forecasting, which produced the research last year, says that biases often creep into forecasts subconsciously. “We call that wish-casting,” he adds. “People want to share good news. And most people think it is good news if coal consumption decreases.”

Others are more blunt — saying the IEA’s forecasts were obviously wrong. “I just looked at those forecasts and thought they were nuts,” says Tom Price, commodities analyst at Panmure Liberum. Price expects that coal use will keep ticking up by about 0.5 to 1 per cent each year. “Over a very long timeframe, coal is a dying industry, but it is not going to die within 5-10 years as people expected,” he says.

Some optimists do expect the world will soon reach peak coal. Not only have renewables prices plummeted, but the advent of cheap energy storage in batteries is allowing renewables to provide “firm” power around the clock, in ways that were not possible before.

In China, during the first quarter of this year, power demand grew, but generation from coal dropped, due to an increase in renewables. Over the past 12 months, China’s emissions are down 1 per cent compared to the same period a year earlier.

Even if that shift does finally prove to be permanent, it will still be later than hoped.

|

|