|

Signature Sponsor

Why the World Cannot Quit Coal - Part 1

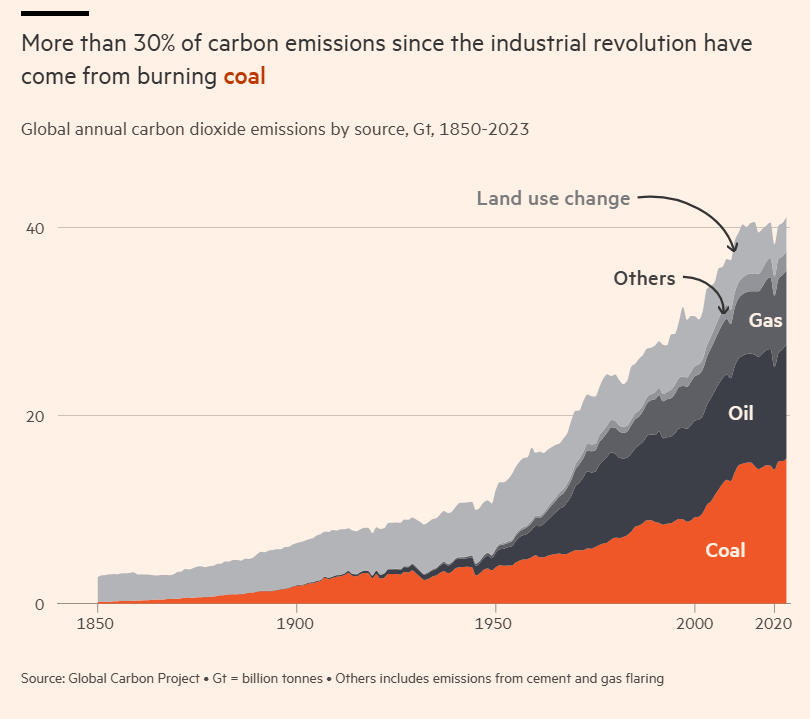

June 19, 2025 - Ten years after the signing of the Paris climate accord, demand for coal is still growing — largely because of India and China — and shows no signs of peaking.

Some of the reasons why the world has not been able to quit coal are obvious, and some are less so. Coal is cheap and abundant — particularly in developing economies such as China, India and Indonesia, which have all been racing to expand their electricity systems to meet growing demand.

Wind and solar energy have been growing at a record pace over the past decade, but not fast enough to meet surging demand for electricity. And while wind and solar may be cheaper than new coal plants in most places, they do not provide constant power around the clock.

“Coal is evil stuff, from an environmental point of view,” says Sir Dieter Helm, professor of economic policy at Oxford university, pointing to its climate effect as well as the impact on human health. “But from an economic perspective, it is fantastically cheap, it is widely available, it can be stockpiled really easily, and it produces really intense heat.”

The world’s energy needs are growing so quickly that the world simply needs more of everything, says Helm — more renewables, more nuclear, and more oil, gas and coal. “Very sadly, there isn’t a transition” away from fossil fuels and towards renewable energy, he says — instead, it is an increase, in all directions.

In recent years, several “black swan” events have also tilted energy systems in coal’s favour. The Covid pandemic resulted in big stimulus packages to help with economic recovery after lockdown, and a post-pandemic industrial surge, particularly in China, which is the world’s biggest coal user.

Coal generation peaked before 2020 in more than 65% of coal-using countries, while nearly 15% of countries had their highest coal use yet last year

Electricity generation by source, TWh. 15 countries with the highest cumulative coal used for electricity generation from 2000 are shown

Although energy consumption temporarily dropped at the height of lockdowns, it came roaring back at full force.

David Fishman, a Shanghai-based energy analyst at The Lantau Group, a consultancy, says that China’s Covid recovery was focused on infrastructure and heavy industry “at a time when both energy and carbon intensity were supposed to be declining”.

He adds: “Unless you’re in a position to meet all growth in energy needs with low-carbon sources, using more energy generally means using more coal.”

The pandemic chaos also pushed climate further down on the list of policy priorities, for China and around the world. That happened again when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022 — suddenly, it was energy security, rather than climate goals, that was the top priority for governments.

The energy crisis that followed the invasion helped coal by driving up natural gas prices — making it relatively cheaper to use coal for electricity, in place of gas.

Prioritising energy security also meant boosting domestic energy production in any form, and often meant producing more domestic coal.

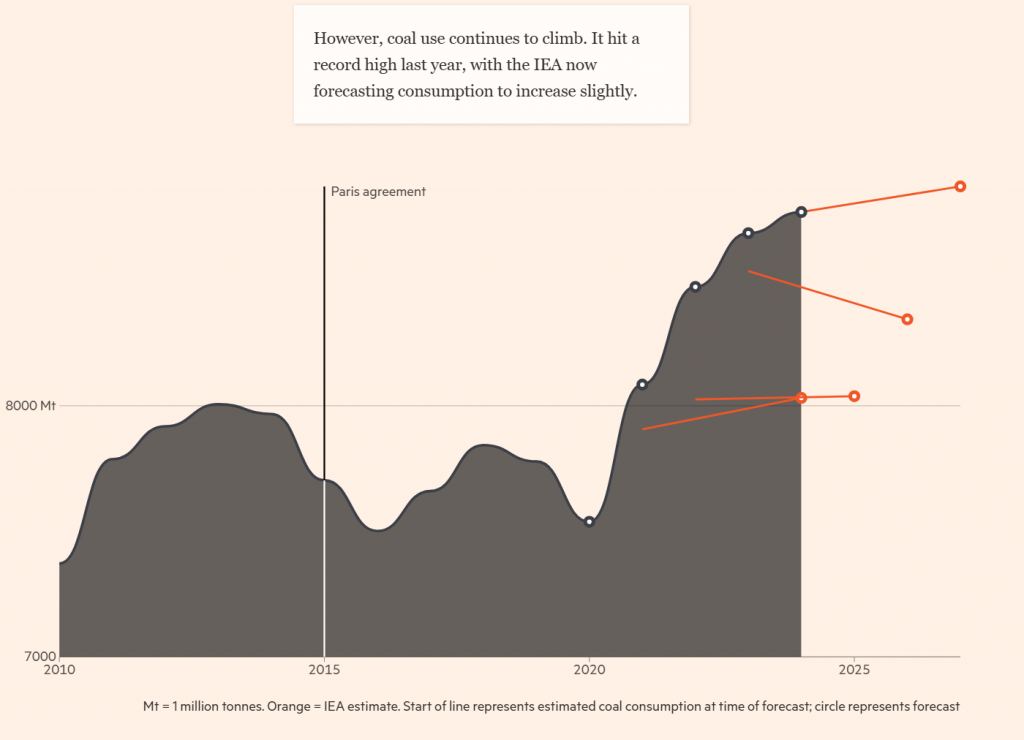

Carlos Fernández Alvarez, head of gas, coal and power markets at the IEA, blames the pandemic and the Russian invasion for throwing off the IEA’s repeated forecasts of peak coal.

“If we have a parallel world in which we remove Covid, and we remove Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I think the coal trajectory would have been very much as expected,” says Alvarez.

He had forecast a coal peak in 2023. But he doesn’t try to call the peak anymore. “We changed our wording, now we talk about a plateau.”

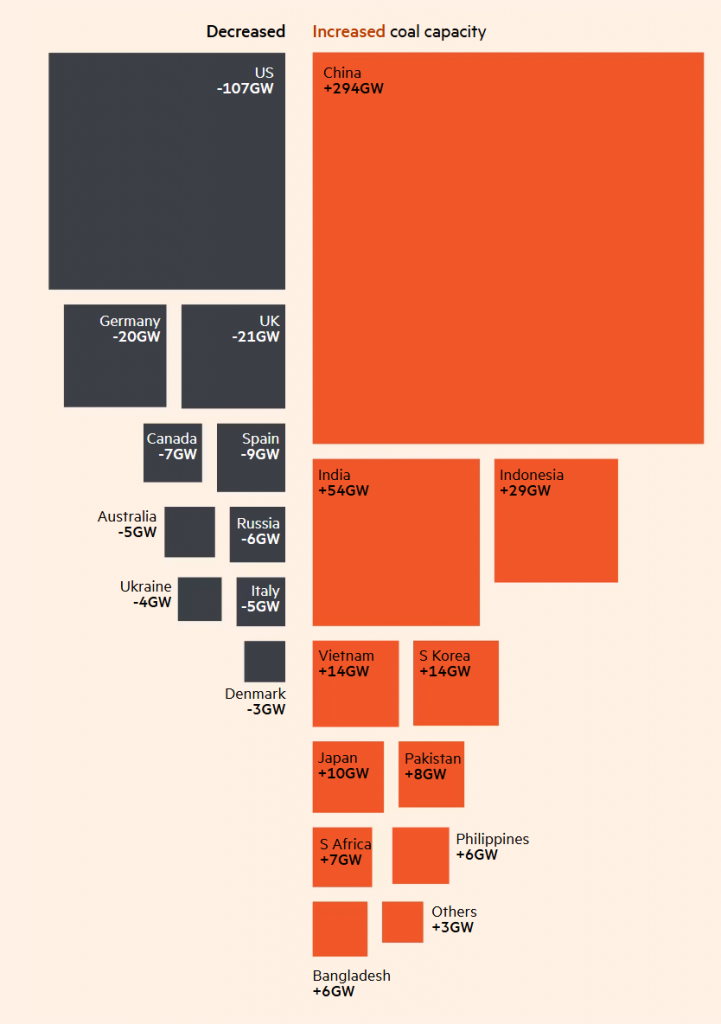

Coal capacity additions outstrip retirements

Change in coal-fired power capacity by country, GW, 2015-2024

“I call it ‘beautiful, clean, coal’. I told my people, never use the world ‘coal’ unless you put ‘beautiful, clean’ before it,” he said in April.

Even as the current US administration doubles down on coal, most wealthy countries are curbing their consumption of it — in fact US coal consumption has dropped significantly over the past decade. Several, including the UK, Austria and Portugal, have quit coal entirely. But these reductions are more than offset by the surge in coal use among the world’s largest consumers, China and India.

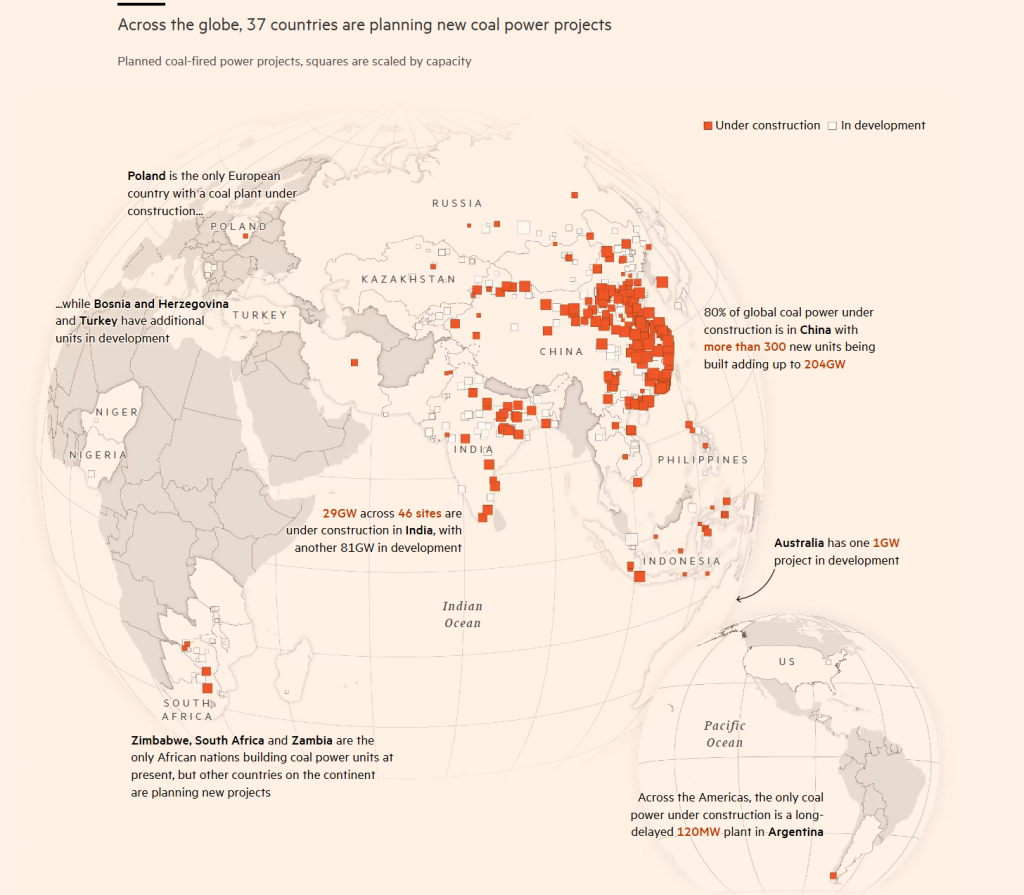

The future outlook for coal demand will largely depend on China and India, which are also the world’s largest producers.

India draws three-quarters of its electricity from coal, despite billions of dollars invested in solar and wind farms over the past decade. The country’s energy-hungry economy is sucking up more electricity than its green sources can currently provide.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants the country to reach net zero emissions by 2070. But an even more urgent priority for the government is to raise living standards, connect everyone to the electricity grid in the world’s most populous nation and turn India into a manufacturing hub to compete with China.

For Coal India, the state-owned company that is the world’s single largest producer of thermal coal, the task is clear.

“We need to grow as an energy sector to fulfil our nation’s demands and our prime minister’s vision,” says PM Prasad, chair of Coal India. “So we have to — since we have the world’s fifth-largest deposits of coal and since we don’t have much petroleum and natural gas. So we are bound to take this coal.”

For him, a key priority is to avoid “load shedding” — an intentional rolling blackout when electricity supply cannot meet the demand.

|

|