Forging a Supermajor: What a Rio-Glencore Merger Means for Metals and Mining

February 6, 2026 - Rio Tinto Group and Glencore PLC have resumed merger negotiations for a potential $260 billion deal that could create the world's largest mining company. The two companies are in preliminary discussions about this strategic move, which is focused primarily on securing a dominant position in copper for the energy transition. If completed, the agreement would consolidate control over increasingly important metals, including copper, lithium and aluminum, reshaping the supply landscape for mining and bulk metals. What does this mean for mining, metal trading and supply chains? In this article, we outline the drivers behind the offer and analyze a merger of the two companies.

The merger would cement the combined entity as the world's largest mining company by market capitalization.

The deal combines Rio's stable, high-margin iron ore mining business with Glencore's trading arm and battery metals portfolio, but also introduces significant geopolitical risk.

A significant culture clash between Rio's conservative approach and Glencore's trading ethos poses a major integration challenge.

The deal would create an entity larger than BHP Group Ltd., pressuring the major to pursue its own transformative M&A or risk being left behind in the race for copper scale.

Merger discussions in late 2024 stalled due to disagreements over corporate culture and leadership, as well as Rio Tinto's reluctance to offer a significant premium. At the time, Glencore had advocated for its CEO to lead the combined entity. However, with new leadership at Rio Tinto, both companies now appear more willing to compromise. Rio Tinto, the acquiring company, is reportedly reconsidering its position on a takeover premium, while Glencore is showing flexibility on management control, acknowledging that an acquiring firm typically installs its own leadership team.

Any combination would be highly complex, requiring the approval of numerous regulators at a time of heightened government scrutiny of natural resources. The combined company could also face a significant culture clash.

UK-headquartered Rio Tinto has until Feb. 5 to submit an official bid for the Anglo-Swiss company.

World's premier copper company

The primary rationale for a merger between Glencore and Rio Tinto is to create a uniquely large natural resources powerhouse. The transaction would combine two highly complementary portfolios: Rio Tinto's dominance in low-cost iron ore with Glencore's market leadership in copper and battery materials. More importantly, it could forge a vertically integrated giant, embedding Glencore's world-class trading and marketing intelligence directly into Rio Tinto's tier-one producing assets.

The combination is almost exclusively centered on copper. Given the scarcity of large copper assets, extended permitting timelines and a market preference for brownfield expansions, this merger represents a strategic acquisition of scale and opportunity. Glencore provides immediate operating assets and a deep project pipeline, while Rio Tinto contributes to financial strength, a lower cost of capital and development expertise to unlock this potential. For Rio Tinto, this would decisively rebalance its portfolio away from iron ore to copper — a metal with a stronger long-term demand growth profile. Crucially, unlike many recent mergers, the primary driver is not asset-level cost synergies. Instead, it is securing copper inventory, project timing and growth optionality that is increasingly difficult to achieve organically.

Rio Tinto holds a unique portfolio of high-quality, long-life assets across iron ore, aluminum, copper and lithium, concentrated in stable jurisdictions and delivering high-margin production. Its Hamersley Consolidated iron operations in Pilbara, Western Australia, are the crown jewel and the world's largest seaborne iron ore supplier, supported by a network of 17 mines and four port terminals. The company expects iron ore production of between 343 million metric tons and 366 MMt in 2026, including an initial 5 MMt to 10 MMt from Simandou Blocks 3 & 4. Once Simandou fully ramps up by 2028, it is projected to reach an annual capacity of 60 MMt.

Regarding aluminum, Rio Tinto is a global leader in low-carbon production through integrated bauxite, alumina and smelting operations across eight countries, with major assets in Canada, Australia and New Zealand. In 2024, record output from Gove and Amrun, coupled with stronger bauxite pricing, drove underlying EBITDA up 61% to $3.7 billion, significantly boosting profitability.

With its Salar del Rincon lithium asset in Argentina, Rio Tinto sits directly in the battery materials supply chain, securing a growing foothold in the energy transition beyond its traditional bulk commodities.

Glencore has complementary assets, including a global marketing network and vertically integrated operations across coal, copper, nickel and cobalt, coupled with its recycling infrastructure. According to 2024 data, Glencore ranks as the world's second-largest cobalt producer, third-largest nickel producer, fifth-largest copper producer and seventh-largest coal producer. The company is projected to supply about 870,000 metric tons of copper by 2026, representing approximately 4% of global output. In nickel, Glencore maintains a leading position supported by assets such as Sudbury Operations, and exerts substantial influence in the global cobalt market through key operations, including the Mutanda, Kamoto and Murrin Murrin mines.

Due to its global presence, some of its assets are in more geopolitically risky locations. These include the Kamoto and Mutanda copper-cobalt mines in Democratic Republic of Congo, Antamina in Peru, the polymetallic porphyry deposit El Pachon in Argentina and several coal assets in South Africa.

Financial and market implications

Glencore and Rio Tinto have two distinct models. Rio Tinto is an asset-heavy operator whose revenues are dominated by iron ore, which consistently delivers robust EBITDA margins of about 70%.

Glencore's strength stems from its dual-engine model. Approximately 72% of its adjusted EBITDA comes from industrial mining assets across coal, copper, nickel, zinc and cobalt. The remaining originates from its global trading marketing division. Though lower in margin than mining, the trading business provides large, stable cash flows largely decoupled from cyclical price swings, thus acting as a natural hedge.

The proposed merger would form a company with combined EBITDA exceeding $260 billion, positioning it as the world's largest mining firm and well ahead of its peers. The combined entity would achieve greater diversification and financial stability. Rio Tinto's iron ore operations — contributing about 42% of the new entity's adjusted EBITDA — would complement Glencore's high-volume, lower-margin trading business and its own industrial mining earnings.

Numbers game: What would Glencore cost?

While the strategic advantages of the merger are well documented, the question of the acquisition price for Glencore remains unaddressed. To frame the financial implications of a potential acquisition, it is crucial to examine Glencore's current market standing. As of the latest trading day (Jan. 21), Glencore's share price is 479.5 pence, pushing its market capitalization to approximately £56.2 billion. This valuation sits near the peak of its 52-week range (205.0 pence-493.75 pence), suggesting that the stock is trading with significant momentum, fueled by strong commodity markets and speculation regarding the merger.

Analyst sentiment is closely aligned with this, with an average 12-month price target of 478 pence.

However, this consensus masks a wide forecast divergence, with targets ranging from a low of 140 pence to a high of 550 pence, highlighting uncertainty around future commodity prices and company-specific risks. From an intrinsic value perspective, the average broker consensus for net asset value (NAV) per share is 457.46 pence, indicating the market is pricing the company at a slight premium to its underlying assets. Furthermore, its valuation on an earnings basis is reflected in an enterprise value/consensus EBITDA multiple of 6.43x, a typical level for the sector.

If we assume a 25% premium on the Jan. 7 closing price, the implied price paid for the potential merger's reserves and resources is $343 per metric ton. This figure aligns closely with the average of $344/t observed across the 15 comparable transactions in our study, which includes the potential Anglo American–Teck Resources transaction, valued at $613/t. This valuation discount may reflect the market's apprehension toward Glencore's riskier asset portfolio and environmental, social and governance challenges, potentially offering a value-accretive entry point for Rio Tinto, if it can successfully navigate these complexities.

Pit-to-port powerhouse

The two businesses have very little direct overlap at the operational level. We believe the main area for creating synergies would be creating a fully integrated mining and trading company. Unlike Rio Tinto, Glencore is both a mining company and the world's largest diversified commodity trader. Its marketing division would serve as a key channel to sell the combined entity's physical production, optimize logistics, capture margins through price arbitrage and integrate a global recycling business for metals such as copper. The combined entity would become the world's largest producer of mined copper, bauxite, seaborne iron ore and thermal coal. The new organization would achieve a scale across the entire commodity value chain, from pit to port to end user, securing dominance in the energy transition through critical minerals such as copper and nickel.

Regulatory, antitrust hurdles

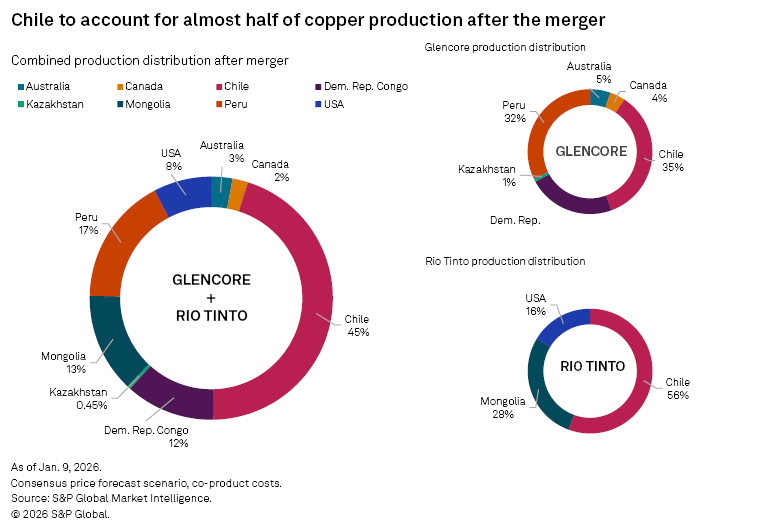

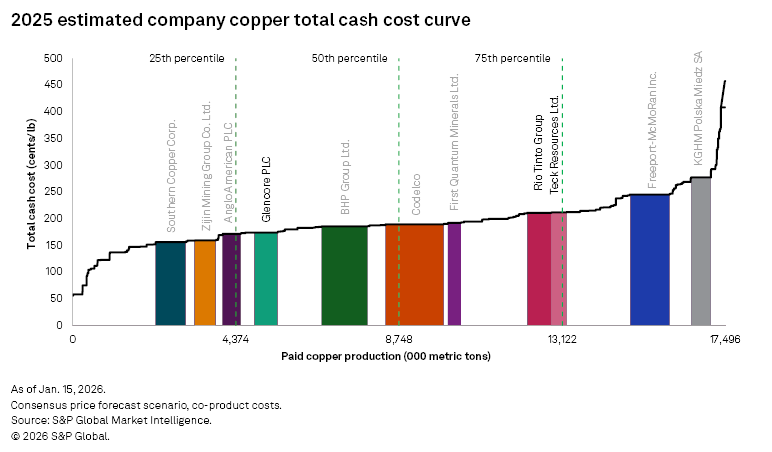

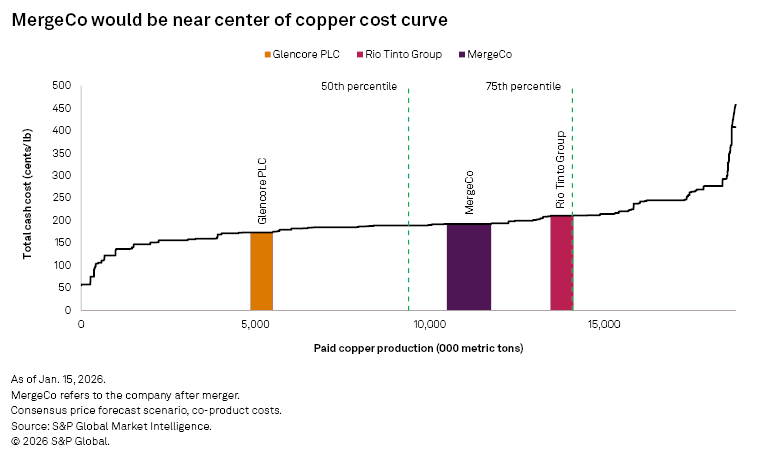

The most immediate and profound challenge presented by the merger lies in copper. Each company is already a major producer. Their combination would create the world's largest copper producer, controlling about 7% of global mined copper supply in 2026, at approximately 1.7 MMt.

South America would form the core of the new entity's copper portfolio, with Chile alone representing 45% of its production. This is primarily driven by major assets such as Glencore's Collahuasi mine and Rio Tinto's Escondida operation, which together are projected to contribute approximately 350,000 metric tons per year of attributed copper output to the new entity in 2026. Additionally, the inclusion of Glencore's mine in Peru would expand the company's footprint in that country, and Rio Tinto's Oyu Tolgoi mine in Mongolia ranks third in production contribution, accounting for about 13% of the new entity's total output, having produced 345,000 metric tons in 2025.

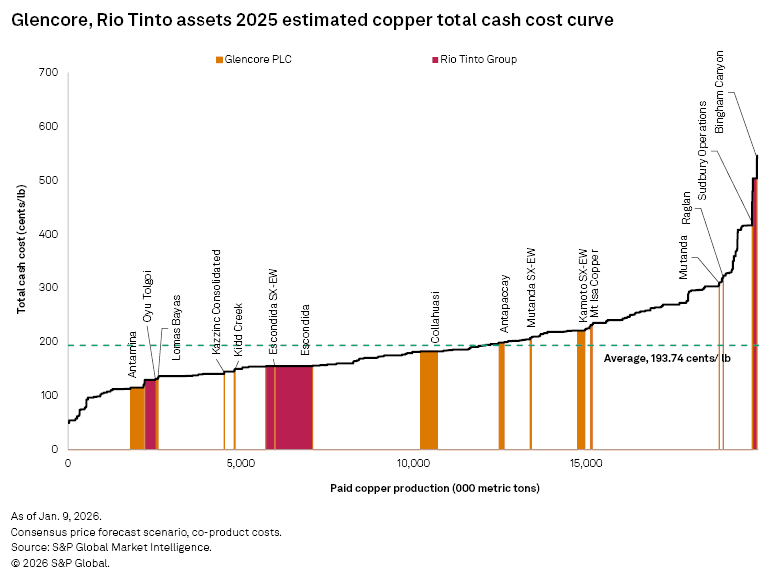

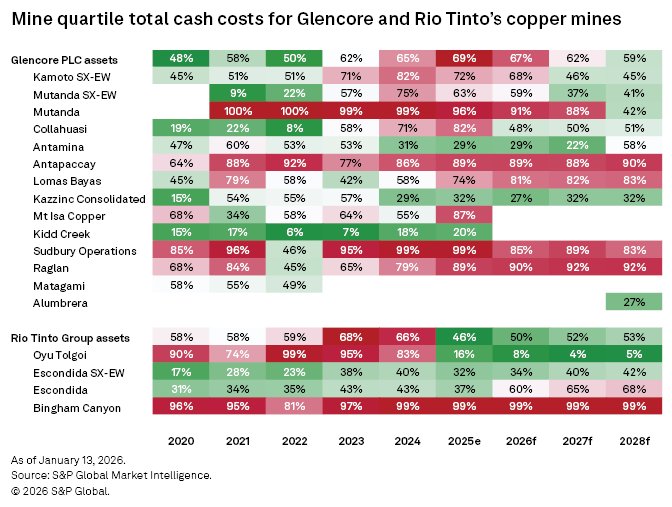

Glencore maintains a competitive cost profile, with assets including Antamina in Peru, Lomas Bayas in Chile and Kidd Creek in Canada all situated in the lower half of the 2025 total cash cost curve. However, its Collahuasi mine, jointly operated with Anglo American PLC, faced severe water scarcity in the first half of 2025, significantly reducing output and leading to a downward revision of Glencore's overall copper production guidance for 2026. It also continues to contend with declining head grades, which have increased costs and compressed margins.

Rio Tinto's copper portfolio is mainly positioned in the lower half of the global cost curve, with the Oyu Tolgoi mine serving as a notable example. Following its transition to underground mining in 2023, Oyu Tolgoi has achieved a sharp reduction in operating costs through access to higher-grade ore. The mine's total cash cost is forecast to be $1.25/lb in 2025 and is projected to stabilize below $1.20/lb from 2027 onward.

Regulatory bodies such as the European Commission and the US Justice Department would likely need to consider whether the proposed concentration level is unacceptable for copper, a key and supply-constrained commodity. Authorities might expect substantial divestitures — potentially including the sale of entire world-class copper mines, thereby undermining a core synergy of the merger. Meanwhile, China's Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) may see the deal as an opportunity to secure access to key copper assets, echoing its approach during Glencore's merger with Xstrata Ltd. in 2013.

In addition to its copper operations, Rio Tinto's Pilbara iron ore assets in Australia are of strategic national importance. Consequently, any transaction transferring partial or complete control of these operations to a foreign-based, trading-focused entity such as Glencore would face rigorous review by the Australian Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) and could result in a veto. Similarly, regulatory concerns would arise in Canada over Rio Tinto's Iron Ore Co. of Canada Inc. and its aluminum assets.

Capital expenditure, project pipelines

Glencore expects annual capital expenditure of between $5 billion and $7 billion over the next three years, allocating 35%-40% to copper projects as it continues expanding its copper portfolio. The company forecasts that its copper output will rise organically from 810,000-870,000 metric tons in 2026 to 1 MMt by 2028, reaching 1.6 MMt by 2035. Near-term growth will be driven initially by brownfield projects, including the restart of Argentina's MARA and the expansion of Chile's Collahuasi, targeting a mill throughput increase to 210,000 metric tons per day. The potential greenfield development of the El Pachón project in Argentina is in the feasibility study stage. To support its 2035 goal, the company estimates that total organic growth investment in copper will reach approximately $23.4 billion.

Rio Tinto's annual capital expenditure is forecast to reach approximately $10 billion from 2026 to 2028, driven by significant growth in Simandou, Oyu Tolgoi and Salar del Rincon. This period will include peak construction at Simandou, targeting full annual production of the 60 MMt by 2028.

Supported by the ramp-up of the Oyu Tolgoi copper mine, the company is targeting 3% compound annual growth in copper output through 2030, aiming to reach 1 MMt by the end of this decade. While the underground expansion at Oyu Tolgoi will be mostly completed within this window, sustaining capital and optimization investments will continue. Beyond 2030, organic growth is expected to come from projects such as the Resolution project — the largest undeveloped high-grade copper deposit in the US — and the La Granja copper projects, as well as lithium brine assets in Argentina and Chile.

ESG conundrum, culture clash

Rio Tinto has positioned itself as a leader in decarbonization, with a clear target of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. Glencore remains a global coal giant, committed to a managed decline of its coal portfolio while retaining the coal business, viewing it as a cash-generating staple for decades to come, with 35% of Glencore's adjusted EBITDA coming from coal in 2024.

Rio Tinto's potential acquisition of Glencore's core copper resources is complicated by the critical — and perhaps risky — assumption that it is willing to absorb Glencore's coal portfolio. Integrating these coal assets would directly contradict Rio's decarbonization narrative, risking a severe backlash from ESG-focused investors, a potential ratings downgrade and significant reputational damage. While a post-merger spinoff of the coal division — an option Glencore itself considered in 2024 — could mitigate this risk, the viability of this strategy is questionable, as it would strip away a major source of revenue and cash flow.

Rio Tinto is rooted in the long-term, capital-intensive nature of mega-mines, operating with a conservative and stability-oriented culture that prioritizes technical excellence and structured governance. In stark contrast, Glencore derives its sustainable competitive advantage from integrating marketing and production assets — a model fueled by market volatility and trading agility and driven by an entrepreneurial, high-risk ethos focused on sharp dealmaking. This fundamental cultural divergence could pose a significant risk to any potential Rio Tinto-Glencore merger. History underscores this danger. Past mining megamergers — such as the rocky integration of BHP and Billiton or Glencore's own acquisition of Xstrata — reveal how cultural misalignment can undermine synergies, delay efficiencies and ultimately potentially destroy shareholder value.

Race for copper scale: Pressure on BHP

Currently, all major diversified mining giants are competing for copper resources. In 2023, BHP spent A$9.6 billion to acquire OZ Minerals. In 2024, the appeal of copper resources drove BHP to attempt two acquisitions of Anglo American, though both plans were ultimately abandoned; in the same year, it also intervened in the Teck Resources deal.

BHP Group is now seen as the most likely disruptor to this potential merger. However, since BHP and Glencore are major global producers of metallurgical coal, any merger attempt would almost certainly face antitrust hurdles. Theoretically, BHP could acquire Glencore in its entirety and later divest its coal assets to secure regulatory approval, but such an operation would be highly complex. Additionally, as BHP CEO Mike P. Henry nears term-end, advancing a transformative deal of this scale would pose significant practical challenges.

If Glencore and Rio Tinto were to merge, the combined entity would likely surpass BHP in both market capitalization and global copper production, relegating BHP's flagship copper business to a distant second. BHP now stands at a critical juncture: It must either accept being overtaken in copper scale or take on the risks of mergers and acquisitions at the right moment.

A potential union between Rio Tinto and Glencore is more than a simple consolidation; it is a strategic gambit to forge an unparalleled supermajor built on the complementary strengths of Rio's low-cost production and Glencore's trading prowess. Yet, the very elements that make the combination compelling also sow the seeds of its greatest challenges. The combined entity's market power in copper would invite intense regulatory scrutiny, potentially forcing divestments that dilute the deal's primary rationale. Furthermore, the stark cultural divide and the ESG conflict posed by Glencore's coal assets represent fundamental integration risks that cannot be understated. While the industrial logic of creating a copper behemoth for the energy transition is undeniable, the question remains whether these immense regulatory, cultural and environmental hurdles can be overcome without destroying shareholder value. Should they succeed, the merger would not only redefine the top of the mining hierarchy but also set a new, aggressive benchmark for competitors in the global pursuit of critical minerals.